Most people don’t think much about dirt. In fact, we tend to focus more on how to scrub it away than why we should treasure it.

Time to change our perspective.

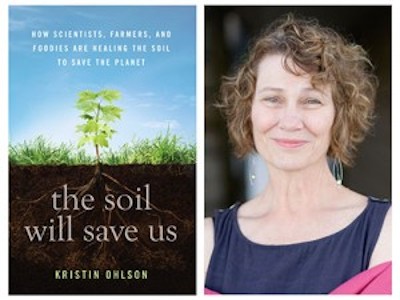

In The Soil Will Save Us: How Scientists, Farmers, and Foodies Are Healing the Soil to Save the Planet, journalist and frequent Experience Life contributor Kristin Ohlson elevates the little-discussed topic of soil health into a call to arms. If we can reestablish our connection with the microorganisms beneath our feet, she writes, we might fix everything from the food system to climate change.

As an organic farmer myself, I hear plenty about soil — sometimes more than I’d like. I love growing luscious vegetables, but I find the topic of soil as dull as mud (don’t tell my farmer friends; I might get disinvited to potlucks).

That’s why Ohlson’s book is so striking: She’s created an accessible, even suspenseful look at why soil matters and how deeply it’s connected to pollution, water purity, food quality, even the increase in obesity.

Ohlson also argues that restoring soil health could help resolve climate change.

Just like trees, soil absorbs and holds carbon, mitigating the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

But thousands of years of conventional farming and ranching, as well as property development, have led to the loss of 80 percent of the carbon from the world’s soil. That carbon is now floating in the atmosphere, messing with the stability of our climate.

By drawing the carbon back into the soil through better management, Ohlson says, we might be able to undo climate change. The soil could indeed save us.

Ohlson’s hopefulness and curiosity buoy every chapter. There are some major challenges, she acknowledges, but there are signs of progress, too. Ranchers are sitting down with wildlife defenders; municipalities are creating compost programs; health-conscious consumers are demanding to know the origin of their food. All these actions can combine to help green the countryside and make soil a priority.

Ohlson artfully demonstrates that soil health is crucial for global initiatives to improve the planet’s health. Her discoveries, though, can also be enlightening at a small-scale, practical level — also known as your backyard.

She kicks off the book with a lyrical account of raking leaves in the autumn: Unlike her neighbors, Ohlson collects them to spread over her lawn, not to uncover it. “It wouldn’t make sense, all those leaves on the lawn, unless you knew something about the incredible life in the soil,” she writes.

By providing a glimpse of that life, she allows us to develop greater appreciation for what’s just below our feet — and why we all should fight to protect it.

Q & A With Author Kristin Ohlson

By Anjula Razdan

Experience Life | What is the relationship between carbon in the soil and excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere?

Kristin Ohlson | Most people think that the overload of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere comes exclusively from the burning of fossil fuels, but that’s not true. People also began adding CO2 to the atmosphere thousands of years ago through the ways they used the land.

Much of the carbon that’s now in our atmosphere came from the soil. How did it get there? It had been accumulating there for millions of years before mammals evolved, through a partnership between plants and the microorganisms in the soil. We can’t see these organisms with the naked eye — and we had no idea they were there until fairly recently — but the earth beneath our feet is teeming with tiny creatures.

There are an incredible 6 billion microorganisms per tablespoon of soil. The partnership between these microorganisms and plants created the basis for just about all life on Earth.

Here’s how it works: Plants remove carbon dioxide from the air through photosynthesis and convert it into carbon-based sugars and protein to fuel their growth. But plants use only about 60 percent of this carbon-based food themselves. The rest of it is sent down to their roots, where the microorganisms cluster like pigs at a trough.

The roots ooze out a carbon meal for the microorganisms. In exchange, the microorganisms leave behind mineral nutrients the plants need, which they’ve liberated from sand and rock.

That carbon cycles through the soil as the microorganisms both eat it and use it to build tiny structures for protection and to hold water. As the carbon gets more concentrated, it is “fixed” in the soil, semipermanent, until hit by a disturbance, like plowing.

EL | You write that “land misuse accounts for 30 percent of the carbon emissions entering the atmosphere.” In what ways does our land management release carbon into the air?

KO | Most agricultural lands are still plowed — and today’s plows are more powerful and plunge deeper than those of our forebears. Land is also disturbed for urban development. Any time land is cleared of vegetation and left bare, the carbon at the surface will oxidize and become carbon dioxide. Fires also send huge amounts of carbon dioxide into the air, and in many parts of the world, forests are burned to create new agricultural land.

EL | Many technologies, such as solar energy and wind energy, promise to help reduce the amount of carbon dioxide we produce. But you note that none of them will reduce the amount of carbon dioxide already in the atmosphere. What can reduce it, you say, is improving the overall health of the soil. Can you explain?

KO | Many scientists and farmers are now working to maximize the carbon-fixing partnership between plants and soil microorganisms. They’re trying to disturb the soil as little as possible — for example, shifting from plowing to no-till agriculture, in which just a tiny slit is made in the soil to receive seed, then pinched shut. They’re mimicking nature and increasing the density and diversity of plants above ground so as to feed a greater diversity of soil microorganisms underground. They’re figuring out new ways of making compost that creates super-healthy soils. And they’re grazing animals in ways that mimic the behavior of ancient herds to make the soil even healthier.

EL | How can everyday folks help save the soil?

KO | Many ways! First, buy sustainably raised or organic food from local producers and advocate for public food policies that encourage environmentally responsible, sustainable farming methods. Many small farmers and ranchers understand the importance of soil health and work hard to enhance the partnership between plants and soil micro-organisms. They’re making the land healthier. Industrial farming, on the other hand, just keeps making it sicker.

Second, build soil health on your own property. Eighty percent of American homeowners have a yard. Increasing the diversity and abundance of the plants there helps improve the soil and is quite easy to do. Make sure every bit of ground is covered by either live or dead plants, so the microorganisms have some sort of carbon to eat.

You can also make the soil under your lawn healthier by using seed mixtures containing several varieties, including clover, which provides nitrogen to the grasses. Avoid chemical fertilizers; they disrupt the partnership between the plants and the soil microorganisms.

This Post Has 0 Comments