In the spring of 2008, I was moving my three daughters from my beloved home state of Oregon back to the East Coast. My husband had a great new job in New York City and was commuting between there and Portland. Before me were the tasks of selling our house, finding one in New Jersey, getting the girls into new schools, and saying goodbye to my parents. I spent my time cleaning for prospective buyers, jettisoning old clothes, and feeling really, really anxious.

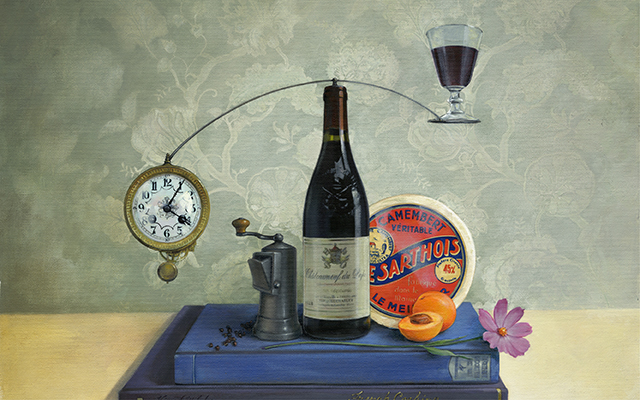

The Sipping Point

At night, I found myself drinking a third glass of wine to cope with the lump of sadness that seemed to have lodged itself permanently in my throat.

Within a few weeks, I began to see that this more-than-usual drinking wasn’t helping, and I scaled back. But I also realized that if a healthy eater and disciplined exerciser like me could start to be careless with my drinking, it could happen to anyone.

Soon, I began noticing women’s drinking as a cultural trope. In my new suburb, I saw women secretly dumping their empty wine bottles at the recycling depot instead of leaving them in their curbside bins. I met moms who joked about bringing flasks to school-board meetings.

Wine-loving women also showed up in popular culture: books, movies, and certainly on TV. On The Good Wife, The Real Housewives, and Scandal, big goblets of wine seemed like characters themselves. On Facebook, I found groups like “OMG I So Need a Glass of Wine or I’m Gonna Sell My Kids” and “Moms Who Need Wine.”

The trend became so striking to me that I spent three years researching and writing about it in my recent book, Her Best-Kept Secret: Why Women Drink — And How They Can Regain Control.

Here’s what I learned from federally funded studies, talks with clinicians and researchers, and plenty of marketing surveys, as well as what I discovered about promising new strategies that seem to work best for women who want to cut back or quit drinking altogether.

Why Women Drink

A wide range of data confirms that women are drinking more now than at any time in recent history. They drink the majority of the 800 million-plus gallons of wine consumed in the United States each year.

Over the past few decades, Gallup pollsters have found that the better off and educated a woman is, the more likely she is to drink. White women are more likely to imbibe than women of other racial backgrounds, but national studies conducted in the last 30 years have found that the number of women who say they’re regular drinkers has risen across the board.

In a sense, the rising drinking rate among women could be seen as a sign of parity with men. But while women tell their daughters they can do everything boys can, drinking is one example where that’s a bad idea.

Biologically, women are more vulnerable to alcohol’s toxic effects. Female bodies have more fat (which retains alcohol) and less water (which dilutes it) than male bodies. Women drinking the same amount as men their size and weight become intoxicated more quickly.

Men also produce more of the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase, which breaks down alcohol before it enters the bloodstream. This may be one reason why alcohol-related liver and brain damage appear more quickly in heavy-drinking women than men.

Women have additional risk factors for drinking to excess. They are twice as likely as men to suffer from depression and anxiety disorders, and often medicate their negative feelings with alcohol. And those who had eating disorders or were sexually abused are also more prone to turn to alcohol, researchers say.

According to Richard Grucza, PhD, an epidemiologist at Washington University in St. Louis, heavy drinking begins in college for many women. Even though women outnumber men on college campuses today, activities are still dominated by male culture, and that involves a lot of drinking — in dive bars, at tailgate parties, at fraternity houses on weekend nights.

Many women continue this excessive drinking when they join the work force, particularly if they’re in male-heavy fields like banking and tech.

And so it goes as the stress of life mounts — when work deadlines loom, when teenagers get sassy, when partnerships falter, when aging parents have health problems.

High Anxiety

It’s clear that women aren’t just drinking more than ever before. They are also worrying more about their drinking. Sharon Wilsnack, PhD, a neuroscientist at the University of North Dakota, pioneered the study of women’s drinking habits in the 1970s. In the early ’80s, she found that one in 10 women answered yes to the question “Are you concerned about your drinking?” By 2002, that number jumped to one in five.

That rise is reflected in the number of women who’ve sought help: Between 1992 and 2007, the number of middle-aged women entering rehab nearly tripled.

Mary Ellen Barnes, PhD, an addiction specialist who treats women with alcohol problems at her outpatient clinic in Rolling Hills Estates, Calif., links many women’s increased drinking to milestones in their lives: divorce, death of a parent, or leaving a career to stay at home with kids.

When life changes disrupt structure, women can find themselves adrift, bored, anxious, and lonely as they try to power through.

“Alcohol is a well-known and time-tested way to medicate all of these conditions,” Barnes says.

The mixed feelings a woman might have staying home with kids, the anxiety she might feel about an empty nest, or the pain she might experience losing a loved one. Drinking can seem like an easy fix for all of these challenges — at first.

So what does it mean, exactly, to have a drinking problem? According to American health officials, anything more than a drink a day is risky for women. (Notably, authorities in France, Italy, and Spain, where life expectancy is longer, set the safe threshold at double that — and sometimes higher.)

Women need to feel powerful, not like victims of something beyond their control.

Many of the women I interviewed said that the limited recommendations in the United States was one factor in driving their drinking underground. A few glasses slide into a whole bottle, which becomes an embarrassing habit they feel they need to hide. And at that point, many perceive that their options for help are limited to the abstinence-based model of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), which can pose specific challenges for women.

AA was developed in 1935, when knowledge of brain chemistry was in its infancy; the group’s primary reference text has remained virtually unchanged since its initial publication in 1939. Its general recommendation is that members declare they are powerless over alcohol and accept that they have a chronic, progressive disease whose only cure is abstinence.

While this may be a reasonable solution for some severely alcohol-dependent people, that’s only about 10 percent of excessive drinkers, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The remaining 90 percent are left with the choice between drinking too much and declaring their powerlessness — a declaration that may well produce the same stress for women that triggered their excessive drinking in the first place.

More-nuanced perspectives on alcohol use might prove more helpful to women who want to drink less or quit altogether. To classify problem drinking, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (known as DSM-5), used by mental-health professionals, now uses the term “alcohol use disorder” (AUD), which denotes a spectrum. This replaces the older terms “alcohol abuse” and the much-older “alcoholism.”

And here’s the good news: The vast majority of women with AUD fall within the mild to moderate range.

What’s more, there are new evidence-based ways to change and moderate your drinking habits. And research shows moderation is a realistic goal for most: A recent CDC study of more than 138,000 adults found that those 90 percent of excessive drinkers who are not dependent on alcohol could successfully moderate their drinking with the help of evidence-based strategies and clinical preventive services.

Many new peer-led support groups for changing alcohol use deploy tools that have been proven to help people learn new behaviors (see next page for examples). They stress personal responsibility; the ability to shift one’s thoughts, feelings, and beliefs; and the individual’s own capacity for change.

Those messages are especially important for women, Barnes says: “Women need to feel powerful, not like victims of something beyond their control. It gives women power to feel they themselves can change.”

For many of those women who have crossed the sipping point, these options are welcome news.

Strategies for Scaling Back on Alcohol Consumption

Drinking sometimes seems so intertwined with stress relief that many women I’ve interviewed find themselves coming home and reaching for the wine before they even get their coats off. If drinking has begun to feel more urgent than relaxing, you may want to check out these tools, which researchers and counselors have found effective in helping shift the focus away from booze and toward healthier behaviors.

Moderation Management (MM) and its companion online program, at ModerateDrinking.com, are included on the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s list of evidence-based programs. MM offers live group and online meetings, and uses cognitive behavioral tools to help members reduce their drinking to manageable levels.

The MM protocol suggests starting by making a list of the problems drinking has caused, as well as the benefits you hope to gain by drinking within moderate limits. This helps strengthen resolve.

Members abstain from alcohol for a month while learning skills for how to avoid and moderate drinking. They also learn to identify and manage triggers that lead to overdrinking.

The group suggests members launch new activities — evening workouts, birding walks at dusk, cooking classes — that can fill the time drinking once absorbed.

After the period of abstinence, members can begin drinking cautiously, being mindful of their limits (never more than three drinks a day, or nine per week for women), often with the help of a journal.

MM does not view slips during this period as failures, but rather as lessons that can be instructive on how you might be more mindful in the future. Ideally, this will allow for eventual moderation.

“Drinking becomes a treat you savor, not a habit you have to feed,” one woman told me.

Harm Reduction is another behavioral technique aimed at reducing the negative consequences associated with alcohol and drug use. One group, HAMS (harm reduction, abstinence and moderation support), encourages members to name an objective — drinking more safely, reducing drinking, or quitting — and come up with a plan to get there.

The group has live and online meetings where members can exchange tips. They encourage an abstinence period as one of 17 elements (rather than steps) on the way toward healthier drinking habits.

There are several concrete tools for consuming more mindfully: keeping a record of how much you drink; setting limits on the number of drinks you’ll have before you imbibe; hydrating frequently to lower your blood-alcohol content; adding abstinence days to your week; and setting time limits — starting later, ending earlier — for when you plan on drinking.

One woman I interviewed also kept a real-time drinking diary. With each drink, she recorded her thoughts, feelings, and her assessment of her cognitive and physical capabilities. In the morning, she could see for herself how “capable” she was after four drinks. She posted the log on her refrigerator as a reminder that after two drinks, she was unable to fully enjoy playing guitar, reading, or cooking a great meal.

She says the exercise helped her distinguish the difference between short-term pleasure and long-term happiness.

“I like having access to my brain,” she told me. While a few glasses of wine brought her relief from the stresses of her job as a business owner, she also learned that playing her music and reading literature that she could remember in the morning made her more satisfied — and happy.

Alcohol and Women’s Bodies

While moderate drinking has been found to reduce the risk of heart disease, diabetes, and ischemic stroke, excessive drinking is a different story — especially for women. Because women are more biologically vulnerable to alcohol’s toxic effects, they run a greater risk for various health problems as a result of overdrinking. Here are just a few.

Hormone Disruption

Hormones affect how a woman metabolizes alcohol. During ovulation, when estrogen levels are high, the intoxicating effects of alcohol can set in faster. The estrogen in some birth-control pills can slow alcohol metabolism, which leads to a quicker buzz. Alcohol can also increase the levels of estrogen and other hormones associated with hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer.

Weight Gain

The body prioritizes processing alcohol over fat and carbs, which means it can take longer to burn off food consumed when drinking to excess. Studies also show that we tend to consume more food when we drink. In addition, excess drinking can increase the stress hormone cortisol, which can increase fat storage in the midsection.

Skin Aging and Dehydration

Excess alcohol dehydrates the entire body, which is most visible on the skin. Many health experts suggest drinking a glass (or more) of water with every alcoholic beverage.

Digestive Problems

Because alcohol irritates the stomach lining, it can interfere with the body’s ability to absorb nutrients (this is also partly why you feel queasy after a few too many). Alcohol is also a common trigger for heartburn and reflux because it relaxes the sphincter muscle between the stomach and esophagus.

Sleep Disturbance

Researchers have found that alcohol can decrease the duration and quality of sleep, as well as increase wakefulness in the middle of the night. Investigators at the London Sleep Centre discovered that while alcohol can lull us to sleep, it can also overrelax the respiratory muscles. This can cause pauses in breathing throughout the night, which disrupts sleep.

Brain and Liver Damage

Because women’s bodies contain more fat and less water than men’s and also produce less alcohol dehydrogenase, they’re more vulnerable to the effects of acetaldehyde, a possible carcinogen that is created during the breakdown of alcohol molecules. This makes them more vulnerable to brain and liver damage from drinking. Women also develop alcohol-related liver problems over a shorter period of time than men, and are more likely than men to develop alcoholic hepatitis.

This article originally appeared as “The Sipping Point” in the July/August 2015 issue of Experience Life.

This Post Has 0 Comments