It’s a message that’s been drummed into health seekers’ heads over the past several decades: Read the nutrition label.

It’s such common counsel today that it’s easy to forget that up until about 50 years ago, the phrase was rarely heard. Prior to the 1960s, there were hardly any nutritional labels to read, in part because there just weren’t that many packaged, processed foods to put them on.

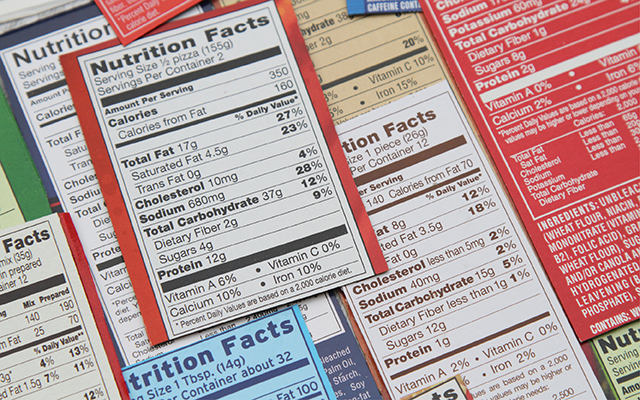

What we know as the Nutrition Facts panel, required by law on most packaged foods, is a thoroughly modern invention. To understand why present-day label reading is so fraught with urgency, complexity, and confusion, it’s good to know a little something about that label’s history.

Up until the late 1950s, most foods you could buy were actual whole foods — meats, vegetables, grains, fruits, nuts, seeds — or they were very simply and predictably processed versions of those things.

Flour, sugar, butter, and lard, for example, were single-ingredient food products that many people cooked with at home. They were produced by basic, widely understood processes (flour was made from ground-up wheat; butter was made from churned-up milk), so until margarine rose to popularity, there wasn’t a lot of mystery about what these sorts of edibles contained.

Back then, nobody saw the need for labels to state the bleeding obvious. Nobody was interested in a chemical breakdown of their daily food products.

Relatively few people longed to be told how many individual servings a given package contained, or how many calories and grams of fat or carbohydrates were contained in each serving, or what percentage of a daily recommended limit or target that serving might represent.

Astonishingly, most people didn’t worry at all about those things. They mostly just ate moderate, reasonable quantities of whole, simply prepared foods — just as they’d seen their parents and grandparents do through generations of customary at-home cooking and eating.

Then things changed. Lots of things. We developed new agricultural methods, new industrial machinery, new chemical science, and new manmade ingredients. Along with all of that, we got an extraordinary profusion of new, novel, highly palatable, and surprisingly cheap processed-food and processed-beverage products.

But the change didn’t stop there. We also got television and television advertising. We got dramatic social change, with many women taking full-time jobs, and fewer families preparing meals and eating together at home around the supper table.

In the span of two generations, the unimaginable became unexceptional: TV dinners, fast-food drive-throughs, frozen pizzas, supersize servings, and all-day soda drinking.

And not surprisingly, we started seeing a corresponding, dramatic rise in health problems — weight gain, type 2 diabetes, heart disease.

Suddenly people were more concerned about their health and a bit more eager to know about what was in their food. The food industry, meanwhile, was excited to make health claims about their foods in order to better appeal to customers.

And so it was that by the late 1960s there was a call for nutrition labels on processed foods. In 1969 the White House Conference on Food, Nutrition, and Health recommended the Federal Food and Drug Administration develop a standardized system. But it wasn’t until 1990 that the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act was signed into law, mandating that the Nutrition Facts panel be featured on virtually all processed-food products.

Unfortunately, that label has always had some real limitations. First, the element that offers the most meaningful nutritional insight — namely, the ingredients section — is often hard to find and takes up the least amount of space.

That section is preceded by a complex assortment of information on factors like calories, total fats, saturated fats, and cholesterol that are hard to make sense of and not very relevant to health. The listing of a few specific nutrients — vitamin A, C, calcium, and iron — seems largely pointless in the context of the vast assortment of other nutrients required for good health, and the fact that processed foods are rarely the best source of those nutrients anyway.

So what’s a savvy label reader to do? Here’s my strategic counsel:

1. Find the ingredients list first. When you can, choose foods that are made primarily from whole, unadulterated foods and minimally processed food ingredients. Avoid foods whose first ingredients consist of various forms of flour, starch, industrial oils (e.g., soybean, corn, safflower, canola), and sugar. Also avoid products that contain high-fructose corn syrup or partially hydrogenated oils (trans fats), or that have a trailing list of chemical additives, artificial flavorings, and colors.

2. Don’t choose foods based on caloric content. Some very healthy foods, like nuts and avocados, are relatively high in calories. And many foods marketed as low-calorie or reduced-calorie are actually less healthy than their regular counterparts — either because they contain artificial ingredients or because they have a higher glycemic index.

3. Don’t avoid foods just because they contain fats. Read some of the articles in related content below to better understand the current science on why fats are an important part of a healthy diet, and why saturated fats are no longer widely thought to be universally unhealthy.

Check ingredients lists to see where the fats come from. If they are from olive oil, coconut, nuts, seeds, avocado, pastured meats, wild-caught fish, heavy cream, or butter (and if the other ingredients are reasonably healthy), that’s probably a good thing.

4. Don’t assume foods with saturated fats or dietary cholesterol are inherently unhealthy. Again, you’ll want to read up on the current science and then make up your mind, but know that many experts now see refined flours and sugars — not saturated fats — as the biggest nutritional factors driving heart disease. And the most recent version of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans clearly declares that cholesterol is “not a nutrient of concern.”

This important correction is long overdue (as Experience Life has been asserting since the early 2000s), but sadly, it will likely take decades more before most Americans move beyond the counterproductive, cholesterol-phobic dietary dogma that has confounded their eating decisions for the last half century. Please, don’t wait that long: Start seeing the “Cholesterol” line on the Nutrition Facts panel for what it has always been — meaningless.

5. Don’t put too much stock in labels. It would be nice to believe that those responsible for shaping our nutritional guidelines and labels (including new ones due out next year) are immune to industrial and political pressure. It would be nice if we could all quickly scan a simple label and know everything we need to know about how it might affect our health.

Of course, it would also be nice if the nightly news opened with a parade of adorable baby elephants. Until that starts happening, your best bet is to get good at decoding the confusing labels we have to deal with now, while also accepting that many of the healthiest foods you can eat — fresh, whole foods — carry no labels at all.

So yes, keep on reading those labels. Just take what you see there with a grain of, er, sodium.

This Post Has 0 Comments