I’m standing in a circle with 10 fitness enthusiasts in an open field, the brilliant Pacific Northwest sunshine taking the edge off the chill in the air. Clapping his hands, Frank Forencich, a 61-year-old with the muscularity of a college fullback, gives the group a simple directive: “OK, let’s play!”

With that, he charges a petite, vital woman named Dawni Rae at full speed, arms outstretched as if to throw her to the ground. In one fluid move, Rae sidesteps the attack, grabs a shoulder, and sends him sprawling to the ground in a harmless forward roll. Everyone — Forencich, Rae, and the assembled, multinational group of participants — bursts into laughter.

We take turns attacking and defending, then move on to other activities: keep-away with medicine balls, spinning Hula-Hoops, and walking around in a half-squat, back to back with a partner, like twins joined at the shoulder blades.

Forty-five minutes later, we’re covered in sweat, breath condensing in the air, hearts beating rapidly, muscles aching. No one has been counting reps or working to failure or feeling the burn. Instead, we’ve been having high-spirited, good-natured fun — not unlike the improvised play that school kids enjoy at recess. And the result is an invigorating, effective full-body workout.

For more than a decade, Forencich — author of Beautiful Practice: A Whole-Life Approach to Health, Performance and the Human Predicament and founder of Exuberant Animal, a wellness program based near Seattle — has been making a similar point: Our stressed-out, teched-up, sedentary lives have led us to forget about our bodies. Exercise has become an obligation that we perform by rote, rather than a vital, engaging activity that stimulates learning, facilitates vitality, and fosters social connection.

Supported by the growing scientific field of “play studies,” Forencich believes that physical playfulness — vigorous, lighthearted, exploratory movement — is an essential, but oft-forgotten, key to physical and mental health. He holds regular workshops and retreats to allow participants to experience this firsthand.

“Play gives you all the physical benefits of moving while also connecting your sensory systems to the world around you,” he explains as we wrap up our day. “It’s the bridge between your body and the environment.”

It may also be the very thing that makes the ways you move more interesting, efficient, and fun again. Just like when you were a kid.

Purposely Purposeless

So what exactly is play? One dictionary defines it as “occupying oneself in an activity for amusement or recreation.” Another describes it by what it’s not: serious.

In the animal world, play is usually easy to identify. Dogs chase each other and mock-fight, pretending to growl, their claws harmlessly retracted and backing off before truly biting. Lions, tigers, and bears play in a similar fashion.

Among humans, play is a broader concept, encompassing activities like games, sports, gambling, and even painting. There’s a reason a theatrical performance is called a play.

Defining play is also subjective: Skydiving may be a blast for you but terrifying for your aunt — or vice versa. Bridge may be a hoot for your brother, stultifying to you. One person’s play can be another person’s poison.

Stuart Brown, MD, founder of the National Institute for Play in Carmel Valley, Calif., a nonprofit committed to “bringing the unrealized knowledge, practices, and benefits of play into public life,” defines it both objectively and subjectively.

First and foremost, he says, play is “apparently purposeless.” In his book Play: How It Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul, Brown writes, “Play activities don’t seem to have any survival value. They don’t help in getting money or food. However, the brain circuits that prompt play are housed in the survival centers of the brain.”

There are long-term, extrinsic benefits to playing: Sport and art, for example, may eventually bring wealth and fame to athletes and artists. But for an activity to qualify as play, that’s not the immediate focus.

“Play is done for its own sake,” continues Brown. “The cultural commonly held misconception about play is that it is trivial, or just for kids. That’s why some people think of it as a waste of time.”

Brown also defines play as having these characteristics:

- It’s voluntary: No one who is forced onto the baseball field and hates every minute of it is really playing.

- It has inherent attraction: It’s naturally fun and exciting to the player.

- It has improvisational potential: It’s structured — but with room for spontaneity.

- It instills a sense of freedom from time: When you’re fully engaged in play, you lose track of the minutes ticking by.

- It brings a diminished conscious–ness of self: “We stop worrying about whether we look good or awkward, smart or stupid,” writes Brown.

- It inspires a desire to continue the activity: You feel an urge to do it again and again.

- It flows from deeply embedded intrinsic motivation: Its rewards, in addition to being fun, sustain increased mastery and lifelong motivation. “It is how children — and most adults — fully engage in the world,” Brown says.

Risk and novelty are fundamental to human play. Somersaults are fun — and a little risky — when you first learn them. Once you master them, you might need to learn other moves so playfulness doesn’t become drudgery.

Though it’s not required, partnership is another beneficial component. Working together toward a common goal or going head to head in a friendly competitive spar adds an element of fun that’s difficult (or impossible) to experience on your own. A sense of camaraderie can infuse even menial tasks with an undeniable sense of fun.

“Play is an antidote to fear,” says Forencich at the end of our long but exhilarating play-filled day. “It’s a way of saying, You’re safe to risk a little: Have fun, and you won’t get hurt.”

Our Innate Need to Play

Every creature — animal and human, young and old, male and female — engages in “apparently purposeless” play, but why?

One answer is practice. Lion cubs, for example, tussle playfully with their siblings to learn skills they’ll later apply to hunting antelope. Our ancestors were responding to a similar evolutionary impulse when they invented games and organized sports to prepare themselves for hunting and battle. Amidst all the frivolity, the argument goes, vigorous physical play builds coordination and strengthens muscles to sharpen us for the dangerous business of survival.

This Darwinian explanation has merit, but it’s not the whole story. The benefits of play appear to run deeper.

Based on his long-term studies of rats and play, Sergio M. Pellis, PhD, professor of neuroscience at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta, Canada, explains that exposing young rats to an “unpredictable loss of control” in play fighting “produces adults who are more able to deal with the vicissitudes of life.”

This appears to be true for humans as well, and it applies to both sedentary and active forms of play.

Playing a musical instrument as a child not only improves the ability to discern pitch and rhythm but also staves off memory loss, cognitive decline, and poor hearing later in life. One Harvard study found motor and auditory improvements after just 15 months of musical training in early childhood.

Two recent studies found that young girls who play sports are fitter as adults and also have better education, career, and health prospects. And a 2010 study discovered that practicing visual arts fostered more than an appreciation of Van Gogh: Among patients with chronic illness, art classes resulted in improved well-being, reduced stress, and measurably better medical outcomes.

Play may also help us learn more effectively. A study of rats found that those raised in a “social, playful, and otherwise stimulating environment” were faster learners than those raised in less-stimulating environments. Rats that were moved into these enhanced environments showed increased neuron production in the hippocampus, an area of the brain vital to memory and learning.

A 2013 study of Emory University students found that reading novels — a form of cognitive play — has lasting beneficial effects on our brain connectivity.

So play’s benefits are neurological as well as physiological. The urge to play resides in areas of the brain less sophisticated and more impulsive than the areas that drive most of our daily actions, says Forencich. And that’s a huge plus: It means that play has the capacity to nudge us away from overintellectualizing and into a more creative, improvisational, intuitive state of being.

Play, it appears, helps our minds — and at the same time, helps us get out of our heads.

A World Without Play

Sadly, though, our jam-packed schedules leave us with little time or patience for the open-endedness of play. “There’s this huge misconception in modern society that play is a waste of time, that it’s a distraction from the real work of being alive,” says Forencich. “In fact, it’s integral to life. It’s a big part of what keeps us productive and healthy.”

It’s all too common for this innate urge to be stifled — even in our children. Many grade schools no longer allow recess time; and at home, kids flock to digital screens to “play” games.

This “play deprivation” — when it’s a substitute for face-to-face play or immersion in nature — has measurable, detrimental effects, says Brown. Based on the detailed play histories of more than 6,000 people, he concluded in a 2014 Scholarpedia report that healthy play patterns are “linked to personal vitality, resilience, optimism, and well-being.” A lack of play, especially in the first 10 years of life, is connected to depression, aggression, addiction, inflexibility, diminished impulse control, and poor interpersonal relationships.

Our bodies and minds are hungry for play. And when it comes to movement, specifically, Forencich argues that the conventional mindset in response to this need — thinking we need to grind away on machines that typically lend themselves to repetitive motions — is incomplete and imbalanced. Many forms of exercise burn calories and tone muscles, he says, but controlled and convenient forms of movement lack novelty, risk, and many of the other qualities that make play appealing and effective.

“As soon as you take risk away, movement becomes less playful and more like work,” he explains. “It’s right there in our word for movement: workout.”

After three days together, the 10 members of the Exuberant Animal retreat pack up to go our separate ways. As is customary following gatherings like this, there are hugs, phone numbers exchanged, plans laid for next steps. But this feels different.

Asked at the end of the retreat what the most powerful part of the weekend was, all of us reply, “The tribe.” This comes after three days of fresh new games, beautiful vistas, and home-cooked meals. Still, of all that was offered, what we liked best was each other.

And that may be the ideal testament to the magic of play. A weekend of playful activity in which we’d risked embarrassment, bruises, and good-natured ribbing had forced all of us to show up fully, fostering a sense of mutual trust while considerably compressing the usual getting-to-know-you time.

As we discovered, and as science is demonstrating more clearly, play isn’t just good for us as individuals. It’s good for a group as a whole — the special something that draws us, and keeps us, together.

5 Ways to Bring On Play

Of the many forms play can take, physical activity may offer the quickest path to playfulness. All exercise is good, of course, but it’s important not to take it too seriously — and to remember that recreation, while scientifically proven to be good for you, should also be pleasurable.

“We’ve come to see exercise as a chore,” says Frank Forencich, author of Beautiful Practice: A Whole-Life Approach to Health, Performance and the Human Predicament and founder of Exuberant Animal. Sets, reps, and heart-rate monitors can be great tools, but if there’s no joy at the root of exercise, you’re missing out on many of the mood-boosting, brain-building benefits play has to offer.

There are no absolutes when prescribing play. Some exercisers may find the traditional approach — tracking pounds lifted and distance covered, for instance — intensely satisfying, while others may enjoy incorporating a few of Forencich’s suggestions to make their workouts more playful.

1. Choose Fun Toys

Convergent exercise equipment — such as leg-press and other strength-training machines — has a single function. Divergent equipment — medicine balls, kettlebells, even logs and stones — offers many possibilities. Whenever you can, choose the latter. “Med-balls, Hula-Hoops, and wobble boards inspire exploration, imagination, and playfulness,” says Forencich. “Even in the context of a gym environment, you can get really pumped using these tools.” (For more ways to make fitness fun again, visit “Are We Having Fun Yet”.)

2. Generalize — And Switch it Up

We often “take the play out of play” by overspecializing, says Forencich. Committing to one sport at an early age has been linked with overuse injuries, burnout, and inactivity later in life. To keep your favorite sport or your weekly workouts from turning into drudgery, switch gears. Every few months — perhaps with each change of season — change your activity. Strive for general function and fitness rather than mastery of a single activity or sport.

3. Set Limits — But Have Fun With Them

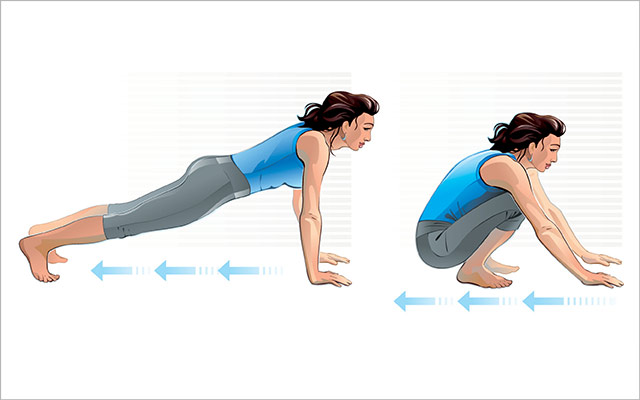

Unlike kids, adults often have trouble with purely open-ended play. “It’s better to set boundaries and explore inside them than simply to say, ‘OK, let’s play,’” says Forencich. Trying to work your lower body? Come up with as many different ways to perform a lunge as you can (forward, backward, sideways, jumping) and do five reps of each in one minute. Want to hit your upper body? Do the same with pushups. Cardio? Think of as many creative (but safe!) ways of ascending and descending a stairway as you can. (For workouts inspired by primal movements, check out “The Exuberant Animal” and “Animal Flow Fitness”.)

4. Take it Outside

The gym can work fine as an all-purpose play place — especially if it has plenty of open space, opportunities for games, and divergent exercise equipment. But outdoor environments like parks, wooded trails, and beaches offer ever-changing terrain and light, which, like natural play partners, keep you constantly on your toes. “Going outside is pretty fundamental,” says Forencich, who conducted all our movement sessions outdoors. “If you can play outdoors, you’ve pretty well cracked the code.” (Find tips for taking your workouts outside at “50 Tips for Taking Fitness Outside”.)

5. Make it Social

Working out with a group or a partner exponentially adds to the level of complexity — and possibilities for playfulness — of any movement. Rather than carrying a set of dumbbells across the room, try carrying a partner, piggyback style. Rather than pushing a weighted sled, try pushing a partner who’s providing resistance. And whenever possible, to the extent you feel comfortable, include others in your workouts. (For a fun partner workout, see “The Workout: Pair Up for Power”.)

Your Unique Play History

You don’t need to quit your job and go live in a yurt to resurrect your natural play instincts. One step you can take is to go over your personal “play history” — a chronology of activities and events that felt timeless, freeing, and authentic. This is not an elaborate quiz, says Stuart Brown, MD, founder of the National Institute for Play, but rather begins with a simple prompt: Spend some time thinking about what you did as a child that really got you excited and gave you true joy.

“Find that joy from the past, and you are halfway to learning how to create it again in your present life,” he explains.

Key questions to ask yourself:

- When have I felt free to do and be what I choose?

- What have been the impediments to play in my life?

Over time, this process may help you rediscover a forgotten interest in gymnastics or art, or perhaps a more interactive and lively approach to your current job.|Telling someone what makes for good play is a little like explaining a joke, says Stuart Brown, MD, founder of the National Institute for Play: Talk about it too much and the magic is lost. But it’s hard not to have fun performing Frank Forencich’s “Solo Short Form,” below. Use it as a warm-up for a regular workout, a do-anywhere “movement snack” to break up sedentary activity, or to create a longer and more involved workout by expanding and exploring whatever piece of the form you wish.

Frank Forencich’s Solo Short Form:

Instructions: Approach the following sequence of moves as if it were a dance, flowing easily from one move to the next and allowing the movements to affect your breath, stance, and center of gravity. Bend your knees and move around as you play, exploring variations of speed, intensity, and range of motion throughout the entire sequence. There’s no suggested duration or rep range for these moves. Allow yourself to be guided by sensation and enjoyment rather than the clock, advises Forencich.

- Rhythmic Arm Swings. Assume a staggered stance, left foot forward. Swing your arms alternately, forward and back, with increasing size and intensity, bending your knees and lowering your center of gravity with each swing of your arms. Stay loose, allowing the movement to travel through your spine and hips. Switch up your legs periodically.

- Flutter Kicks. Raise both arms overhead and wave them, alternately, 6 inches forward and back, as if “kicking” with your arms. Continue waving the arms, this time standing on your right foot, then your left, for several repetitions.

- Backstroke. Extend your arms and rotate them alternately backward.

- Wax On, Wax Off. Lower your arms, spread your feet to double shoulder width, and draw large, horizontal circles with each hand, as if waxing a car. “Wax” all surfaces of the imaginary car in front of you, dropping low to get the fenders, reaching high to get the roof.

- Shoulder-Hip Rotations. Raise your arms so they are parallel to the floor and bend your elbows roughly 90 degrees. Keeping your upper arms stationary, rotate your forearms forward and back alternately, while simultaneously rotating your hips left and right in tandem with the movement. Explore stance width and side-to-side stepping throughout the movement.

- Horizontal Circles. From a low, wide stance, sweep your arms left and right in large, arcs as if clearing a table. Step into a deep lunge, with your right foot, then your left, as you continue the move. Integrate the movement so your entire body turns as your arms sweep side-to-side.

- Diagonal Reaches. From an athletic stance, reach forward with your right arm while pulling your left into the “chamber” position (palm up, elbow in, heel of the hand touching your lower left ribs); then reverse the movement, extending your left hand while pulling your right into the chamber position. Reach across your body, high and low, then explore the move while standing on one foot.

- Deep Arcs. From a wide stance, sweep your arms as high as you can to the right, then down toward the floor in front of you, bending your knees, then as high as you can to the left. Alternate sides.

- Sword Cuts. Take an athletic stance with your right foot forward. Hold the handle of an imaginary sword in your hands, right hand in front. “Cut” downward in front of you, swinging the sword to the left of your body. Smoothly switch your feet and swing the imaginary sword upward again, this time swinging the sword down with your left hand in front. As you master the movement, reach higher at the top of the swing and lunge lower at the bottom.

- Figure Eights. Trace repeated, horizontal figure eights in front of your body with your arms. Stand on one foot, then the other. As with all the other moves, vary the size, speed, stance, and intensity of each repetition.

- Stillness. Stand, feet together, hands at your side. Take several deep breaths.

Photography by Terry Brennan

This article originally appeared in the July/August 2016 print edition with the title “Play On!”.

This Post Has 0 Comments