For much of my adult life, I’ve experienced mild fatigue. It never made me want to crawl under the covers and sleep all day, nor did it inhibit me from pursuing my interests. I’ve never suffered from depression, and until just a few years ago my metabolism burned hot.

During the worst of times, I just felt like I had one foot on the gas and one on the brakes. And with a spirited and seemingly energetic mother who experienced similar issues, I figured this was simply my lot in life.

During the worst of times, I just felt like I had one foot on the gas and one on the brakes.

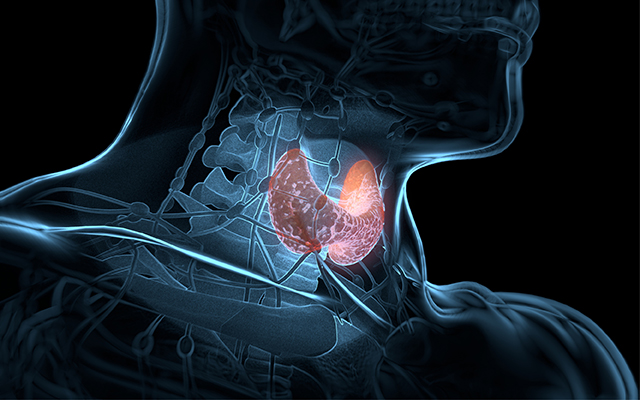

In 2002, at the age of 32, I was told in a routine checkup that my thyroid was “borderline.” I knew that the thyroid was a butterfly-shaped gland in the neck that controls metabolism and energy, but with no further discussion or instruction from my doctor about what borderline meant, I didn’t give it much consideration. I later suffered from symptoms that were, unknown to me at the time, related to the diagnosis. I was chilled in 75-degree weather, had dry skin and itchy eyes, and at times would experience significant hair loss. I was also becoming increasingly restless and impatient.

It wasn’t until 2008 that I discovered I suffered from the most common cause of hypothyroidism, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, an autoimmune condition that causes the body to attack its own thyroid tissue. (For more about autoimmunity, see “Autoimmune Disorders: When Your Body Turns on You“.)

Even though I was trained as a holistic nutrition coach, I knew little about Hashimoto’s. Confronted with the mysterious four-syllable verdict, I countered, “Um, no, I don’t have that, thank you.”

My labs told a different story. When my then-doctor asserted that I had to be on thyroid drugs for the rest of my life — drugs that can cause heart palpitations, shortness of breath, troubled sleep and a host of other side effects — I again blurted, “I don’t think so,” and my journey into sleuthing low thyroid function and autoimmunity began.

It’s estimated that hypothyroidism, or underactive thyroid, affects more than 30 million women and 15 million men. (Hyperthyroidism, or overactive thyroid, is much less common.) “Thyroid dysfunction affects our health systemically,” says family nutritionist and naturopathic endocrinologist Laura Thompson, PhD. “Since the endocrine system [which is made up of glands that produce our bodies’ hormones] is responsible for growth, repair, metabolism, energy and reproduction, any slowing of the thyroid can have significant implications for our overall health.”

It’s estimated that hypothyroidism, or underactive thyroid, affects more than 30 million women and 15 million men.

Datis Kharrazian, DHSc, DC, MS, a leading expert on autoimmunity, further points out in his book, Why Do I Still Have Thyroid Symptoms When My Lab Tests Are Normal? (Morgan James Publishing, 2010), that autoimmune disease accounts for a whopping 90 percent of Americans with hypothyroidism, mostly due to Hashimoto’s. The other 10 percent are afflicted with non-autoimmune hypothyroidism.

Unfortunately, patients with hypothyroidism suffer from symptoms that are rarely traced to a sluggish thyroid. If you’re feeling blue or unmotivated, you may be prescribed an antidepressant. If you’re constipated, you’re told to take a laxative. If you’re having difficulty sleeping, you’re given a sleeping aid. If you’re overweight and having trouble shedding pounds, you’re instructed to work harder at the gym or consume fewer calories (which can actually exact a greater toll on the thyroid gland). And even when conventional docs do diagnose hypothyroidism, the drug regimens they routinely prescribe don’t always do the trick.

The good news is that knowledge of proper diagnosis methods, dietary choices, lifestyle modifications and thyroid drug alternatives can help many people reclaim their health. That’s what happened to me.

I simply focused on whole-foods nutrition and some simple thyroid-friendly lifestyle modifications. I am thankfully now in remission from Hashimoto’s and, motivated by the mantra “We teach what we most need to learn,” I’ve changed the focus of my health-coaching business in hopes that those who have thyroid issues can benefit from my research.

What Is the Function of the Thyroid Gland?

The thyroid is hailed as “the master gland” of our complex and interdependent endocrine system. Put another way, it’s the spoon that stirs our hormonal soup. It produces several hormones that transport energy into every cell in the body and are vital for feeling happy, warm and lithe. The thyroid gland also acts as the boss of our metabolism. Which is why symptoms of hypothyroidism include weight gain and fatigue — as well as constipation, depression, low body temperature, sleep disturbances, difficulty concentrating, edema (fluid retention), hair loss, infertility, joint aches and light sensitivity.

Which is why symptoms of hypothyroidism include weight gain and fatigue — as well as constipation, depression, low body temperature, sleep disturbances, difficulty concentrating, edema (fluid retention), hair loss, infertility, joint aches and light sensitivity.

In part because these symptoms are so common, the thyroid is too often the last place medical practitioners look for a problem. When doctors do choose to run labs, they routinely operate under the misguided conviction that hypothyroidism can be diagnosed via a single blood test of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), which ultimately reveals little about overall thyroid function. And even when a TSH test is relevant, the interpretation of the results is often incorrect.

Because TSH rises as thyroid function wanes, high TSH indicates that the thyroid is underperforming. But many doctors mistakenly believe that TSH over 5.0 is worth treating, when, according to most functional medicine doctors, anyone with TSH over 3.0 has hypothyroidism. (Harvard-educated integrative physician and gynecologist Sara Gottfried, MD, argues that women tend to feel best with TSH between 0.3 and 1.0.)

It’s no wonder thyroid patient and activist Janie Bowthorpe, MEd, author of Stop the Thyroid Madness (Laughing Grape Publishing, 2008), has nicknamed TSH “thyroid stimulating hooey.”

It’s estimated that millions more sufferers could be diagnosed if proper testing was commonplace for Hashimoto’s symptoms. Unfortunately, the antibodies that show the presence of Hashimoto’s — thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAb) and thyroglobulin antibody (TgAb) — happen to be on the list of thyroid labs that most conventional docs don’t perform.

Because thyroid hormones directly act on so many parts of the body, though, it’s essential to follow up with proper lab tests if you self-identify a problem. (For more on lab testing, as well as a simple at-home test, see “Testing in the Lab” and “Testing at Home,” below.) When you’re tested, it’s also a good idea to be checked for adrenal fatigue, since those with hypothyroidism often have some level of the condition and it can be difficult to treat the thyroid without assessing both systems. (For more on adrenal fatigue, read “Pick Yourself Up.”)

Hashimoto’s Treatment

Hashimoto’s is one of the most common forms of autoimmune disease in the United States.

Other examples of autoimmune conditions include rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, lupus, celiac disease, Crohn’s disease and psoriasis. In the presence of autoimmunity, normal tissue is confused with a pathogen, and your body’s immune system mistakenly launches a seek-and-destroy mission against itself. When a person has Hashimoto’s, antibodies specifically attack and damage his or her thyroid tissue.

With the number of people suffering from an autoimmune disease increasing markedly in recent decades (50 million Americans are now affected), researchers are scrambling to find cures.

There are several theories about how autoimmunity is triggered, including childhood trauma, genetic predisposition and exposure to environmental toxins. But most conventional healthcare practitioners are unaware of how to manage it because there is no pharmaceutical for autoimmune diseases. There are only drugs to help ease the diseases’ symptoms. As a result, the underlying issues continue to smolder.

And although supplemental iodine is generally the correct regimen for those 10 percent of patients who have non-autoimmune hypothyroidism, it is not the treatment of choice for those with Hashimoto’s. Too much iodine can overstimulate the thyroid and cause anxiety and sleeplessness. Which is why, according to Kharrazian, if you have Hashimoto’s, taking supplemental iodine is “like throwing gasoline onto a fire.”

Hashimoto’s is one of the most common forms of autoimmune disease in the United States.

Instead, the first line of defense against Hashimoto’s is dietary change. There is a slew of nutritional recommendations you can follow — all of which helped me in my journey toward Hashimoto’s remission — but you should get started by completely removing gluten from your life, which has been shown to trigger a response from the immune systems of even those without digestive gluten sensitivity.

While many health experts suggest that none of us should be eating gluten, Hashimoto’s sufferers have a distinct reason to swear it off, according to Kharrazian. Because gluten protein closely resembles thyroid tissue, he says, eating it puts the immune system in attack mode, exacerbating the problem. There is no such thing as moderation when it comes to gluten and Hashimoto’s, he says, since even the smallest amount can trigger an autoimmune attack for several months.

Thyroid experts also advise eating foods with thyroid-friendly vitamins and minerals, such as vitamin D, iron, selenium and zinc, and avoiding foods that inhibit thyroid health, such as raw cruciferous vegetables, soy, sugar and caffeine. (For a detailed list of nutritional dos and don’ts, see the Web Extra below.)

After changing dietary habits, some people have to turn to thyroid drugs to treat Hashimoto’s. In some cases, medication is required indefinitely, especially when Hashimoto’s has gone undiagnosed for a long time and the thyroid is damaged to the point that it can no longer produce hormones. In my situation, I halted the immune attack with good nutrition and self-care, and there was not so much damage to my thyroid that a replacement hormone was warranted.

I was lucky, but even if you do need thyroid drugs, it’s important to know that they are not always a lifelong sentence. “Often, patients can reduce their medication and sometimes even go off it entirely,” says Thompson. “It depends on the degree and duration of imbalance.”

If you do need drugs, it’s important to work with a qualified doctor to find what type of medication, and what dosage, works well for you. As Gottfried puts it, “Finding the right thyroid drug is like trying on shoes,” and no matter what sort of treatment you may ultimately require, it’s all about experimentation, so don’t lose hope.

The specific hormones the thyroid produces that are most critical to our health are triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroxine (T4), both of which regulate metabolism. The most popular thyroid drug, Levothyroxine (most commonly known as Synthroid), is a synthetic T4-only drug.

In our bodies, T4 is a mostly inactive hormone and nicknamed “the storage closet” or “the lame duck.” It is the forerunner to T3, which is the predominant and active hormone and which has the greatest affect on our health and well-being. The body is designed to convert T4 to T3, but many people have trouble with this conversion, mostly due to stress, hormonal and gut imbalances, and nutritional deficiencies. In other words, if the body is to utilize a T4-only drug, the wheels that mobilize the T4 to T3 conversion need to be well oiled.

Some report a honeymoon period with Levothyroxine, where they feel better initially, only to revert to feeling unwell or have lingering symptoms. The continued health complaints often bring on increased dosages of thyroid meds and sometimes antidepressants or anti-anxiety prescriptions. Simply put, T4-only drugs fail many people.

What often works, however, is a combination T4-T3 medication. Biodentical T4-T3, known most commonly as Armour Thyroid, for example, comes from dried porcine thyroid. These natural hormones have been successfully used since the late 1800s and, after decades of the prevalence of T4-only prescriptions, are gaining use again. Switching from Levothyroxine to “tried and true” Armour Thyroid has proven extremely effective for many people.

Above all else, addressing hypothyroidism is an exercise in becoming a proactive patient. It’s imperative to approach a healthcare provider with informed confidence and to insist on proper testing. If your doctor uses outdated lab-reference ranges or doesn’t test for Hashimoto’s, don’t settle for a “you’re fine” diagnosis. Instead, try to find a functional medicine doctor who understands thyroid issues and knows that there’s rarely a silver-bullet solution. (Go to “Find a Functional Medicine Practitioner” to locate one.)

It takes time and patience to heal, but I’m living proof that you can get there.

Symptoms of Thyroid Problems

The thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland that controls our metabolism and energy and is critical to our overall health. Symptoms of hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid) include:

- Weight gain or the inability to lose weight despite proper diet and exercise

- Fatigue

- Constipation

- Edema (fluid retention)

- Low body temperature

- Infertility

- Irregular menstrual cycles

- Depression

- Low stamina

- Lack of motivation

- Sleep disturbances

- Difficulty concentrating

- Joint aches

- Poor ankle reflexes

- Light sensitivity

- Hair loss (including thinning of outer eyebrows)

- Hoarseness upon waking

How to Test Your Thyroid At Home

Although lab testing is the best way to get an accurate sense of how well (or poorly) your thyroid is functioning, you can do a simple at-home test to get started. Keep a glass basal thermometer beside your bed. (A regular thermometer cannot assess minute temperature shifts.) When you wake up in the morning, at roughly the same time and before moving at all, tuck the thermometer snugly in your armpit and keep it in place for 10 minutes. Remain as still as possible. Remove, take a reading, and record the results. Follow this procedure for three days. If your average temperature is below 97.8 degrees F, you may have an underactive thyroid. (Women should begin testing on the second day of menstruation because mid-cycle, there is a natural rise in temperature with ovulation.)

Gender Gap

Why thyroid disorders affect women more often than men.

Although millions of men experience thyroid dysfunction, women are 10 times more likely to have a thyroid imbalance. The reasons are uncertain, but according to integrative physician and gynecologist Sara Gottfried, MD, the phenomenon is linked to female hormones, since estrogen dominance (a condition in which estrogen levels are high relative to progesterone) has been implicated as a contributing factor.

The interaction between the thyroid and a woman’s reproductive hormones is significant: Hypothyroidism can lead to infertility, miscarriage, premenstrual syndrome (PMS), osteoporosis, endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), irregular cycles, uterine fibroids, low libido and difficulty in menopause.

For many women, thyroid problems first arise during times of hormonal unrest, such as childbearing and periods of prolonged or intense emotional, physical and mental stress. According to Gottfried, “Women are most vulnerable after pregnancy and during perimenopause and menopause. Thyropause — a drop in reproductive hormones that often triggers hypothyroidism — is the main cause of fatigue, weight gain and depression.”

A woman’s hormonal matrix is a bit of a chicken-and-egg scenario. Boosting thyroid function has a beneficial effect on ovaries and adrenals, but the opposite is also true: Resolving estrogen dominance, low progesterone and adrenal fatigue can help rebalance thyroid hormones, too. All the organs and glands talk to each other; they also compensate for each other, explains family nutritionist and naturopathic endocrinologist Laura Thompson, PhD.

“All of these systems need to be aligned,” says Gottfried. “Otherwise, the thyroid can be sidetracked by the ovaries and adrenals, especially in the presence of estrogen dominance and adrenal burnout.”

Thompson agrees: “Estrogen dominance can contribute to hypothyroid conditions, especially in menopause. The use of high estradiol birth control pills can also contribute to low thyroid conditions.”

But men aren’t entirely immune to hormonally triggered hypothyroidism, she notes: “Low testosterone often accompanies low thyroid in both men and women.”|

Testing in the Lab

Many doctors don’t test for thyroid dysfunction at all, and even when they do, they rely on only one blood test (for thyroid stimulating hormone, TSH) that reveals little about overall thyroid function. As a result, millions of people suffering from thyroid dysfunction are left undiagnosed. If you do go to the doctor for thyroid testing, be sure to be tested for Free T3 (FT3), Reverse T3 (RT3), and the presence of two thyroid antibodies, TPOAb and TgAb. The “Free” in front of T3 discloses what is unbound and usable by the body. Reverse T3 is just that — the opposite of T3 — and it blocks thyroid receptors and can cause patients to be unresponsive to any thyroid hormone.

There is some disagreement about what constitutes acceptable lab values, depending on the doctor and the lab. As a result of outdated ranges, borderline hypothyroid patients are often overlooked. Family nutritionist and naturopathic endocrinologist Laura Thompson, PhD, uses functional medicine thyroid-reference ranges. Optimal ranges for FT3 is 2.0–3.0 pg/ml; for RT3, it’s 90–350 pg/ml.

It’s also a good idea to get tested for celiac disease, as Hashimoto’s and celiac are often in cahoots, and to be on the lookout for gluten sensitivity. If your healthcare provider scoffs or tells you that these tests are unnecessary, consider finding a new doctor. In the meantime, you could also seek out comprehensive thyroid-panel testing through direct-to-consumer lab services, like HealthCheckUSA.com or DirectLabs.com.

Nutritional Dos and Don’ts

Autoimmunity or no autoimmunity, drugs or no drugs, it’s vital to treat the thyroid well by eating a thyroid-friendly diet. Here are some of the nutritional recommendations Minneapolis-based holistic nutrition coach Jill Grunewald recommends for her clients.

Macronutrients

The big three macronutrients — fat, protein and carbohydrates — all play key roles in regulating thyroid function.

- A low-fat or nonfat diet or a diet high in nasty trans fats will weaken your immune system and can wreak hormonal havoc. But cholesterol is the precursor to our hormonal pathways, so healthful fats are necessary for energy and hormone production. Quality sources of fat include olives and olive oil, avocados, flaxseeds, fish, nuts and nut butters, hormone- and antibiotic-free full-fat dairy, coconut oil, coconut milk products, grass-fed meats, and many types of wild fish.

- Protein is required for transporting thyroid hormone through the bloodstream to all your tissues. Protein sources include meat and fish, eggs, dairy, nuts and nut butters, legumes (lentils, beans, etc.), and quinoa.

- Low-carb diets are not a good choice for those suffering from impaired thyroid function. Decreasing carbohydrate intake leads to diminished levels of T3 hormones, crucial to your metabolism. Try the complex carbs found in vegetables, legumes, fruits and whole grains.

Micronutrients

Nutritional deficiencies play a significant role in thyroid dysfunction. While they aren’t the cause of hypothyroidism, not having enough of these micronutrients and minerals can exacerbate symptoms.

- Vitamin D — Egg yolks, fatty wild fish (salmon, mackerel, herring, halibut and sardines), fortified milk and yogurt, mushrooms, fish liver oils. It’s best to supplement with vitamin D, as since it’s nearly impossible to get everything we need from food sources. An adequate level of vitamin D is essential, as because it helps transport thyroid hormone into cells. (The standard minimum of 32 ng/mL won’t do it, as levels below this can contribute to disruption of hormonal pathways. Optimal vitamin D levels, I believe, are between 50–80 ng/mL.)

- Iron — Clams, oysters, spinach, white beans, blackstrap molasses, organ meats, pumpkin seeds, lentils

- Selenium — Brazil nuts, sunflower seeds, mushrooms, tuna, organ meats, halibut, beef

- Zinc — Oysters, sardines, gingerroot, whole grains, beef, lamb, turkey, split peas, sunflower seeds, pecans, Brazil nuts, almonds, walnuts, maple syrup

- Copper — Beef, oysters, lobster, crabmeat, mushrooms, tomato paste, dark chocolate, sunflower seeds, beans (white beans, chickpeas)

- Iodine — Primary sources: sea vegetables (kelp, dulse, hijiki, nori, arame, wakame, kombu), safe seafood; secondary sources: eggs, asparagus, lima beans, mushrooms, spinach, sesame seeds, summer squash, chard, garlic

For several dairy-free, gluten-free recipes that will nourish your thyroid, see “Essential Thyroid Recipes“.

Foods That Weaken Thyroid Function

Eating right for thyroid health also means avoiding these foods:

- By definition, goitrogens are foods that interfere with thyroid function and get their name from the term “goiter,” which means an enlargement of the thyroid gland. If the thyroid is having difficulty making thyroid hormone, it may enlarge as a way to compensate for its inadequate hormone production. Goitrogens include cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower, kale, kohlrabi, rutabaga and turnips. Though research is limited, it appears cooking helps inactivate goitrogenic compounds, so don’t shun these foods, especially considering their cancer-fighting superpowers. Foods that are less goitrogenic are millet, spinach, strawberries, peaches, watercress, peanuts and soy.For an update on goitrogens, check out “Goitrogens: Thyroid Busters or Thyroid Boosters“

- Soy is one of the most controversial foods out there. Many believe that it is not fit to consume unless it’s fermented and only then in moderation. Fermented soy includes tempeh, natto (fermented soybeans), miso (fermented soybean paste), and shoyu and tamari (both types of soy sauce). Fermented soy doesn’t block protein digestion like unfermented soy and isn’t a menace to your thyroid. Unfermented soy contains goitrogens, which can stifle thyroid function. Unfermented soy products such as soymilk, soy ice cream, soy nuts and tofu, are reported endocrine disrupters and mimic hormones. Soy blocks the receptor sites in your cells for naturally produced hormones and interrupts the feedback loop throughout your endocrine system.

- Sugar and caffeine are the terrible twosome. These rascals can do a number on your thyroid by further stressing your system. When you have compromised glands, especially hypothyroidism and adrenal fatigue, the last thing you want to do is amp your system with sugar, caffeine and refined carbohydrates like flour-based products, which the body treats like refined sugar.

This article has been updated. It was originally published in the November 2012 issue of Experience Life.

This Post Has 2 Comments

I have messed up my thyroid by taking blue berry and broccoli supplements. It was as though I were eating 8 cups each of blueberries and broccoli. How long will it take my thyroid to get back to normal? I have to have it rechecked in a couple of more weeks. I have completely given up goitrogens or cook them thoroughly.

Thankyou for this information on Thyroid ! There is not enough said about the Thyroid today. This article is so informative and very helpful. So many key points.

Thank you.