Blood is supposedly thicker than water, but when Ethan Watters took stock of his life a few years ago, the San Francisco writer realized that he was more dependent on friends than family. In troubled times, the unmarried 30-something relied on buddies, not his parents or siblings — who lived hundreds of miles away.

“My friends were the centerpiece of my social life,” he says. “They had taken on all the responsibilities that family members typically tackle — connecting me to the city, being a matchmaker and helping me find jobs and places to live.”

Watters grew to believe that such close-knit, nonfamilial social networks were a defining characteristic of modern 20- and 30-something life. As with previous generations, young adults in America tended to leave their families of origin in their late teens or early 20s. But in recent years, Watters observed, this group had been waiting longer and longer to get married and start families of their own. The result was a gap of sorts in which there was no obvious anchor for emotional, social and moral support. Rootlessness only exacerbated the problem: Many young Americans no longer lived in the same city as family members, so they were forced to build or seek out “tribes” of friends who could give the kind of support once provided by nearby kin.

Watters went on to write about this trend in Urban Tribes: A Generation Redefines Friendship, Family, and Commitment. But it isn’t just unmarried people under 40 who rely on “chosen families” rather than what psychologists call “families of origin.” In every generation, in fact, there have been individuals who have survived and thrived, thanks to chosen families — divorcées, single dads, children estranged from their families by alcoholism. Even people who adore their families of origin have come to recognize the benefits of cultivating a second family.

What Is a Tribe?

You may already have a tribe: Who celebrates birthdays and holidays with you? Whom do you call when a crisis hits or when good luck strikes? If “my pals” is the answer, you may already know how a tribe provides social, emotional, spiritual and sometimes even financial support. But if those pals seem only nominally reliable during ups and downs — or perhaps they’re only loosely connected, rather than being a tight-knit safety net — you may want to consider finding or building a tribe. Like nomadic bands of old, a modern tribe may be your best defense against social starvation and emotional attack in a sometimes-lonely world.

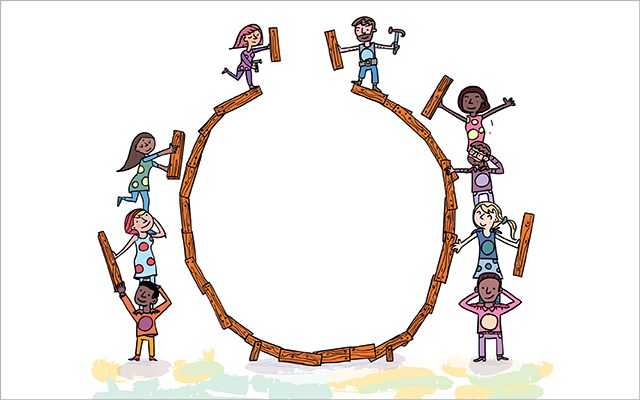

Tribes are both similar to and different from families in several significant ways. From an anthropological viewpoint, tribes are simply extended families — a group of people, often linked by blood, who offer each other food and help in times of need, protection from the outside world, and a sense of collective identity. Early humans probably evolved tribal behaviors in order to survive: After all, an individual who can rely on the help of others in times of conflict, illness or hunger stands a much greater chance of survival.

But contemporary tribes are distinctly unlike families — and even ancient bands — in their governance. Consider the popular show Friends. There’s no chief or matriarch in that fictional modern tribe: Tribes are democratic, or led by a group of committed individuals. Members can enter or leave the clan as they wish, and the group’s activities and agenda are usually the result of consensus and acclaim, rather than top-down decree.

Common Bonds

Modern tribes coalesce in several ways. Often they’re borne out of a shared experience that promotes or requires some level of intimacy, like attending group therapy or living in close quarters. New York City resident Kim Snyder says she found her true-blue circle of friends in a substance-abuse recovery program.

For 13 years now, she and a half-dozen group members have gathered to celebrate milestones, mourn losses and simply enjoy one another’s company. “When you have a close group of friends, you know you can get through anything,” she says.

A shared interest, such as cooking or comic books, may also spark the creation of a tribe. Watters’s tribe began with a group of artists, writers and photographers who met for dinner every Tuesday night. One Minneapolis-based tribe got its start when several liberal members of a large conservative Bible study group split off and started holding their own meetings.

And sometimes simple geographic isolation spawns a tribe. (Remember Gilligan’s Island?) When Pat Sugrue and her husband, Tom, moved from Boston to Alexandria, Va., 28 years ago, they realized that bad weather and traffic would often hamper their efforts to return to Beantown for holiday gatherings with family. So they decided to re-create the festive atmosphere of those familial fetes. Today, they still invite dozens of people to their table for Thanksgiving and Easter dinners. “We consider them all family,” Sugrue says.

Tribal Rites

So if joint experiences, common interests and even shipwrecks can yield tribes, why is it that not every group — a cadre of coworkers or a poker club, for example — becomes a tribe? Many such groups never evolve beyond typical bar-buddy status.

Tribes are bound by trust and intimacy. They shift from “circle of friends” to tribe when their members begin to treat each other like family — offering support without expectation of exact or immediate repayment; sheltering each other from gossip, stress and attack; and looking out for everyone’s overall well-being in life, work and relationships.

An implicit social contract evolves: Tribal membership trumps other ties and situational details. Even if a fellow member doesn’t know everything about you, tribal loyalty compels him or her to come to your aid in troubled times.

As members’ talents and vulnerabilities emerge, tribal roles evolve: the comic, the nurse, the bodyguard, the matchmaker, the sage. Though the roles are different, they balance each other out as members defer to each other’s acknowledged expertise within the tribe.

Tribes also require rites and rituals. Tribal habits create a culture and mythology that can be sustained even as membership in the tribe waxes and wanes. “The members of the group may change,” Watters says, “but the story of that group has central elements that remain. It gives the group a history.” (For more on rites and rituals, see “Up With Urban Tribes” below.)

Finally, every tribe needs an anchor — an individual or core group that convenes the tribe on a regular basis and tends to its overall growth and survival. This takes commitment. It may mean opening your home on a regular basis, or making the phone calls that get everyone excited about an annual ski retreat.

Like families, tribes have a way of shaping their members: Individuals feel more confident, secure, loved and stable. In fact, the blessings that come from “families of choice” may reshape your view of your “family of origin,” changing how you communicate with your parents or broadening your perspective on your own children’s lives.

“Families of choice and families of origin don’t need to be mutually exclusive,” Watters says, noting that his own friends and family now mix at an annual dinner on Thanksgiving. “The love and support we get from one does not take away from the love and support we get from another.”

Up With Urban Tribes

Interested in solidifying your own tribe? Consider the following guidelines, adapted from Ethan Watters’s “Five Ways to Build and Maintain an Urban Tribe” at www.urbantribes.net:

CREATE A WEEKLY OR MONTHLY RITUAL. Seeing each other consistently is the way personal communities form. Some tribes meet to watch a popular t.v. series, some meet as a book group. Others connect every Tuesday night for dinner at the same restaurant. It’s the simple act of repeatedly getting together as a group that forms the bonds that keep everyone close.

CREATE ANNUAL RITUALS. Although you might think of this as simply an extension of guideline No. 1, yearly rituals have a distinctly different purpose than weekly or monthly happenings. Yearly

rituals such as throwing a big New Year’s Eve party or taking a group bike trip require planning and coordination. These are times when the tribe can test itself and its members. Will everyone be able to work well together? Will every member share the burden or will some slough off? By challenging itself with grand yearly rituals, the group tests its value and meaning.

DON’T BE OVERLY POSSESSIVE OR EXCLUSIVE. You may be tempted to define or control who is in the group and who is not. Although your tribe might have a core membership, healthy tribes have

fluid borders. In this way your tribe can both give you emotional shelter and connect you to the outside world. By making distinct in/out judgments, you limit the tribe’s key function of connecting

you to a larger network.

SET UP E-GROUPS. There are many free and friendly ways to facilitate communication within your group. These allow you to easily add and delete people from email lists. Your tribe may have several lists: one for those who play on the softball team, one for those who want to know where Larry’s next gig will be, one for planning the next houseboat trip, etc. Being able to quickly spread information and ideas within the group is one of the distinct aspects of these modern groupings.

This Post Has 0 Comments