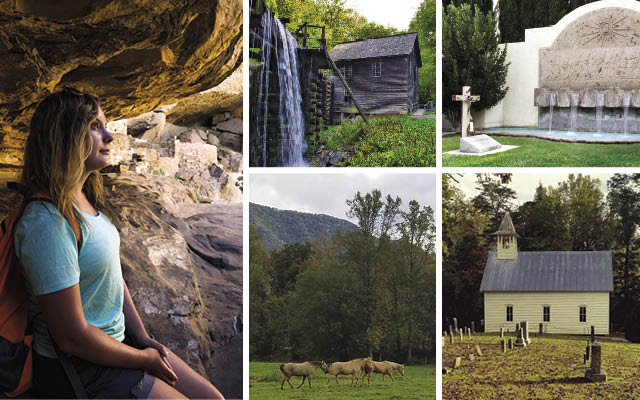

Crows circle above as I meander through the Primitive Baptist Church cemetery in Tennessee. I stop to rake my foot across curling brown leaves and reveal markers etched simply with the word “son” or “daughter.”

A dimming autumn sun has begun its journey downward, and wispy clouds swirl across the tops of the red- and orange-flecked Great Smoky Mountains encircling this lowland.

Horses and wild turkeys graze peacefully on grassland pasture today, but the Cherokee hunted in this verdant valley for hundreds of years. By the late 1790s, they’d built a settlement here known as Tsiya’hi, or “Otter Place.”

Westward movement of white settlers into tribal lands in 1818 created tension among the groups, so the U.S. government began “relocating” the Cherokee. In 1819, the Treaty of Calhoun ended Cherokee claims to the Smokies, yet the valley was named after Tsiya’hi leader Chief Kade.

In 1927, many descendents of the settlers — who built the mills, barns, and churches remaining in the basin — resisted federal-government efforts to establish Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Eventually, their properties were seized through eminent domain.

Incomplete Pictures

“The creation of America’s national parks has been the creation of myths,” author and public-lands advocate Terry Tempest Williams writes in The Hour of Land: A Personal Topography of America’s National Parks.

View a marker inside a park and you’re likely to read an incomplete version of history. It may not reveal that the parks often displaced people, plants, and animals.

But one gift of these hallowed grounds — along with wilderness conservation — is that they reflect as much about our nation and its fraught, violent history as they do about the people and places they honor.

“They can be seen as holograms of an America born of shadow and light; dimensional; full of contradictions and complexities,” Williams notes. “Our dreams, our generosities, our cruelties and crimes are absorbed into these parks like water.”

Despite — or perhaps because of — these inconsistencies, our national parks are incredibly popular among America’s increasingly fractured population. A 2019 survey found that 90 percent of Americans consider the conservation of parks and monuments important, and a majority want more lands preserved.

In a 2018 Pew Research Trust poll, 76 percent of respondents favored a five-year plan before Congress to set aside up to $6.5 billion to address nearly $12 billion in needed repairs.

It seems that legendary naturalist John Muir — who helped draw Yosemite National Park’s boundaries in 1889 — was right when he noted that “thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, overcivilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wildness is a necessity; and that mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life.”

Jog Your Memory

Many of the parks, monuments, battlefields, seashores, and scenic trails that the National Park Service administers have been set aside as important symbols of U.S. history and prehistory. Together, these sites — including the six highlighted here — connect us with our past, help us make sense of the present, and offer valuable insight into how we, the people, might create a more perfect union.

Explore the World of the Ancients

Mesa Verde National Park; Cortez, Colo.

Open year-round, Mesa Verde (Spanish for “green table”) offers a window into the lives of the Ancestral Pueblo people who called it home for more than 700 years between the sixth and 14th centuries.

One of the country’s richest archaeological zones, it was established as a national park in 1906 to protect nearly 5,000 cultural and historical sites, including pit houses, farming structures, and 600 cliff dwellings.

Drive the six-mile Mesa Top Loop and the Cliff Palace–Balcony House Loop, and be sure to park the car and tour the Cliff Palace, Balcony House, or Long House. Those looking for a challenge can trace the footsteps of Ancestral Pueblo elders along one of the park’s strenuous hiking trails — elevations range from 7,000 to 8,572 feet. The 2.4-mile round-trip Petroglyph Point Trail provides an excellent view of a well-preserved rock-art panel.

Never Forget

Manzanar National Historic Site; Independence, Calif.

In the months following the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the forcible removal of anyone of Japanese descent from their homes and communities. More than 100,000 Japanese-American citizens and resident aliens were transported to remote, military-style relocation camps.

Located in the foothills of the imposing Sierra Nevada mountain range, Manzanar offers a ranger-led tour of the barracks as well as an exhibition and film documenting the lives and experiences of the American men, women, and children interned at 10 concentration camps across the United States. A driving tour provides views of gardens, ponds, and a cemetery that were built as acts of resilience and resistance by those interned at Manzanar.

Seek Safe Passage

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park and Scenic Byway; Church Creek, Md.

Human-rights activist Harriet Tubman escaped slavery, alone, in 1849. For the next 11 years, the staunch abolitionist and suffragist worked as a conductor on the Underground Railroad, a network of people — African American as well as white — who offered shelter and aid to escaped slaves from the South.

Using disguises, riding horses and trains, sailing on boats, offering bribes, and relying on the stars to navigate, Tubman rescued about 70 people during 13 trips to Maryland.

Visitors can explore this self-guided, 125-mile, scenic driving tour through the landscapes and waterscapes of Maryland’s Eastern Shore where Tubman traveled. Explore a new visitor center; Brodess Farm, where Harriet spent her early years; the Bucktown Village store, where you can touch what Tubman touched; and Tuckahoe Neck Meeting House, a gathering place for Quaker abolitionists.

Fight for Workers

César E. Chávez National Monument; Keene, Calif.

¡Si, se puede! Yes, we can improve working and living conditions and garner higher wages for farmworkers, said César Chávez, Dolores Huerta, Larry Itliong, and millions of Americans who heeded their call to action.

During the 1970s, the three leaders expanded a farmworkers’ union into a national voice for poor and disenfranchised workers. Their tireless efforts ensured the passage of California’s Agricultural Labor Relations Act of 1975, the nation’s first law that recognized farmworkers’ collective bargaining rights.

The monument is part of a property known as Nuestra Señora Reina de la Paz, the home and workplace of the Chávez family and farmworker-movement organizations. Stop in to explore the visitor center, the memorial garden in which Chávez is buried, and a small desert garden that’s planted nearby.

Rise Up for Civil Rights

Stonewall National Monument; New York City

The Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street in Greenwich Village may not stand out in a jam-packed New York City, but it plays an outsized role in the history of LGBTQ rights.

On a steamy June night in 1969, a series of spontaneous, violent demonstrations — led in part by transgender pioneers, such as Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, drag kings and queens, butch lesbians, and other marginalized members of the LGBTQ community — began as a backlash to continual police raids of local gay hangouts.

The uprisings led to the formation of numerous activist organizations and newspapers promoting equal rights for LGBTQ people. A year later, the first gay-pride marches began; today, they continue annually throughout the world.

Start at Christopher Park and take a 45-minute walking tour of important sites, including the Stonewall Inn and the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop — America’s first gay and lesbian bookstore and the starting point of the first New York Pride March.

Secure Partial Equality

Women’s Rights National Historical Park; Seneca Falls, N.Y.

This site commemorates the first Women’s Rights Convention, which was held July 19 and 20, 1848.

Organizer Elizabeth Cady Stanton and convention speaker Frederick Douglass were later joined by Susan B. Anthony, Lucy Stone, and other white and black suffragists in petitioning for women’s equality. Black female suffragists, however, wanted to secure voting rights not as a symbol of parity with their husbands and brothers, but as a means of empowering African-American communities, which had suffered continual violence after emancipation. This approach was often at odds with the mission white suffragists pursued.

Their joint efforts secured voting rights for white women via the passage of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution. (Black women and men faced segregationist laws into the 1960s.)

Tour Cady Stanton’s home and view the Declaration of Sentiments, which includes this sentence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal.”

This originally appeared as “History Lessons” in the January/February 2020 print issue of Experience Life.

This Post Has 0 Comments