Remember the old song “Dem Bones” and its lyrics, “The foot bone’s connected to the ankle bone . . .”? It turns out, that wisdom is only partially correct. These days, a well-informed physical therapist, bodyworker, or personal trainer will tell you that the foot bone’s not only connected to the ankle bone, but also to the thigh bone, hip bone, back bone, and just about every other tissue in your body.

Health professionals are increasingly viewing the body as a single, integrated structure, composed of parts that communicate with each other through a series of chain-like “slings,” which crisscross the body like seams on a patchwork quilt. These musculoskeletal systems are allied with intersecting highways of fascia — the web-like connective tissue that gives the entire body form and structure — all functioning to create and support optimal movement patterns.

“Understanding how the sling systems function can revolutionize how you exercise,” says Billy Anderson, NASM-CES, a trainer and instructor for Life Time Academy, a personal-training certification program in Chanhassen, Minn.

While they may sound complicated with names like posterior and anterior oblique, deep longitudinal, and lateral, these sling systems serve an eminently practical purpose: to help you move and function with greater coordination, grace, and athleticism.

By implementing movements that activate a group of muscles lying along a particular sling — rather than isolating single muscles — you reinforce actions that are innately healthful and beneficial.

“We’re integrated, three-dimensional creatures moving in three dimensions,” says Erika Mundinger, DPT, OCS, a physical therapist who focuses on orthopedics and sports medicine in Minneapolis. “So it makes sense to train the body like that.”

In the gym, progressive trainers like Anderson and Josh Henkin, CSCS, founder of DVRT Fitness in Scottsdale, Ariz., apply their understanding of sling systems to help clients reach their fitness goals faster and more safely. This results in an innovative and remarkably time-efficient approach to exercise — and an organic foundation for daily movement that helps you feel and function better from head to foot.

Read on to learn how four of the largest sling systems work to produce smooth, safe, athletic movements — and to find exercises for each system that can help you move through your days with greater ease.

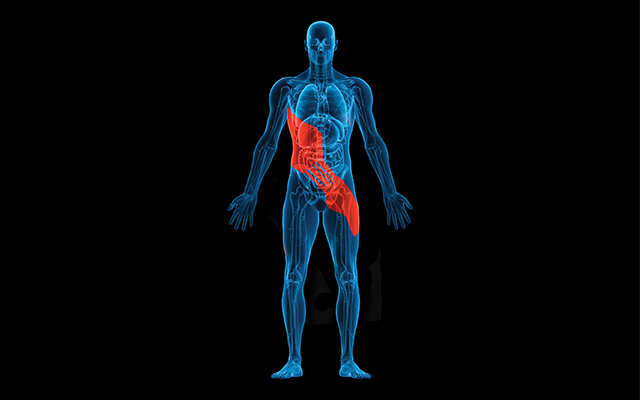

Posterior Oblique System

This group of muscle and fascia includes two intersecting slings that run across the back of your torso.

Illustrations by Paul Price

Illustrations by Paul PriceMade for Walking

One of the most straightforward ways to see the body’s slings in action is a basic activity: walking. While it can easily be dismissed as a simple matter of moving forward or backward, each step in your stride also involves complex side-to-side and rotational motions.

This natural movement creates forces that run diagonally across your torso, from one shoulder to the opposite hip on both the front and back of your torso.

The two slings of the posterior oblique system (POS) form a large X across your back, from each shoulder to the opposite hip. Follow the muscle fibers across the back of your torso on an anatomy chart, and you’ll see that the large muscles on the sides of the upper back (the lats, in gym par-lance) appear almost continuous with those on the backs of the hips (the glutes). Between them is a stretch of connective tissue (the thoracolumbar fascia) whose fibers create the center of the X.

To understand how this works, consider what happens in your body while walking, when you (unconsciously) engage the right-shoulder-to-left-hip sling: As your right shoulder rotates back, your right elbow pulls back, and your left leg kicks behind you. As your right shoulder and arm pull forward, your left leg kicks forward. So any movement where the opposite arm and leg pull or extend back at the same time emphasizes the action of the POS.

“All the fascia, muscles, tendons, and ligaments run along that same diagonal line of motion,” Mundinger explains.

You could argue, then, that the blueprint for cross-body movements — including walking, running, sprinting, and skipping — is etched into our anatomical structure. They’re movements we were born to do.

The Moves

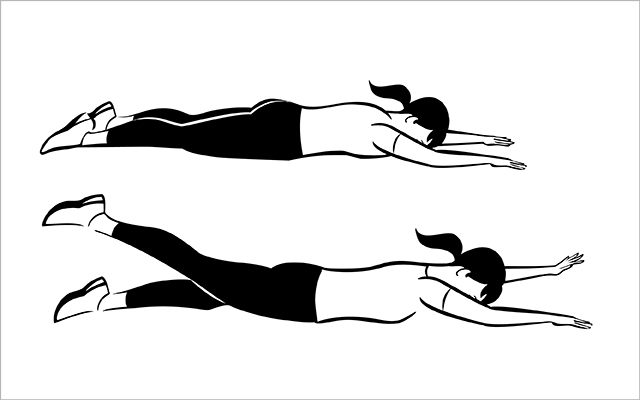

Prone Opposite Arm-and-Leg Lift

Illustrations by Cindy Luu

Illustrations by Cindy Luu- Lie flat on your front side on a padded surface with your legs straight and your arms extended overhead.

- While squeezing your glutes and keeping your neck neutral, slowly lift your left arm and right leg off the floor and hold them there for a five-count, keeping all four limbs fully extended. Don’t wrench your neck to increase the extension.

- Slowly lower your arm and leg to the floor, and repeat on the opposite side.

- Alternate for 10 to 20 reps per side.

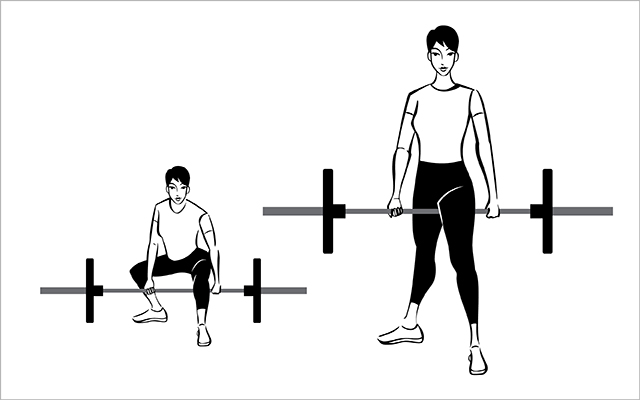

Jefferson Deadlift

Illustrations by Cindy Luu

Illustrations by Cindy Luu- Straddle a barbell and rotate your torso about 45 degrees to your right so your shoulders are squared and your left foot is forward.

- Squat down and take hold of the barbell, using an underhand grip with your right hand and an overhand grip with your left.

- Engage your core, press through your feet, and stand to lift the barbell between your legs. Squeeze your glutes at the top.

- Reverse the movement and repeat for eight reps per side.

- When choosing a weight, start light (such as 10-pound bumper plates) until you are comfortable with the move. It can also be performed with one or two kettlebells.

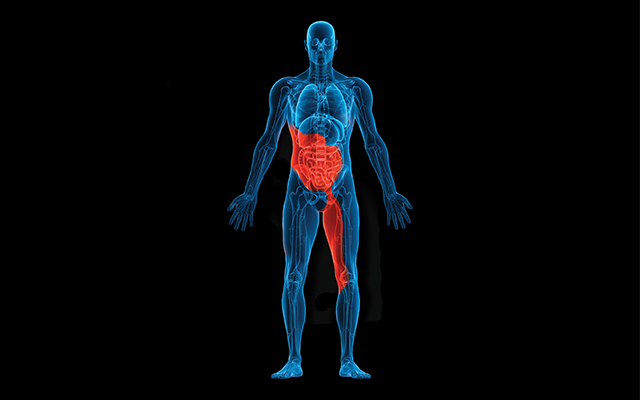

Anterior Oblique System

This group includes two intersecting slings that run diagonally across the front of your torso.

Illustrations by Paul Price

Illustrations by Paul PriceDo the Twist

The anterior oblique system (AOS) is basically the front-side mirror image of the posterior oblique system. It consists of two lines of muscle and fascia, each running diagonally from the sides of your waist to the front of each inner thigh. Between these muscle groups is a sheet of fascia that crosses your abdomen.

As with the POS, the fibers of the AOS — which include several muscles — appear continuous, as if they had evolved to function in concert. The AOS, Anderson explains, works antagonistically to the POS: “As the AOS muscles contract, the mus-cles of the POS lengthen, and vice versa,” he explains.

“Think about throwing a ball,” adds Mundinger. Assuming you’re right-handed, you step forward with your left foot, rotate your hips to your right and then left, and your right shoulder and arm follow like a whip, propelling the ball forward. “The AOS transfers the energy from your left foot through your hips, core, and into your right shoulder and arm.”

The AOS aids in rotation of all kinds: swinging a racquet, bat, or golf club, or throwing a right cross. Off the playing field, it stabilizes your hips and torso as you pull your back foot into the stepping position while walking.

Working the AOS doesn’t just improve gait and make you a better athlete, though; it’s also vital to injury prevention.

“Look around the gym, and most of what you see are straight-ahead movements — pressing, pulling, lunging,” says Mundinger. “In real life, though, we twist and turn all the time.” Driving a car, opening a door, even sitting with crossed legs all involve some degree of twisting in the spine.

By practicing turning movements in the gym, she notes, “we’re less likely to get hurt when rotational movements come up outside the gym.”

The Moves

Bicycle

Illustrations by Cindy Luu

Illustrations by Cindy Luu- Lie on your back with knees bent and feet flat on the floor.

- Press your lower back into the floor and place your hands near your ears, keeping your elbows spread wide.

- Engage your core and lift your feet off the floor, bending your knees to a 90-degree angle, shins parallel to the floor.

- Extend your right leg out straight and rotate your trunk so that your right elbow comes close to your left knee.

- Reverse the movement, and repeat for 15 to 25 reps per side.

- Stop and reset if you lose the core engagement and your back arches off the floor.

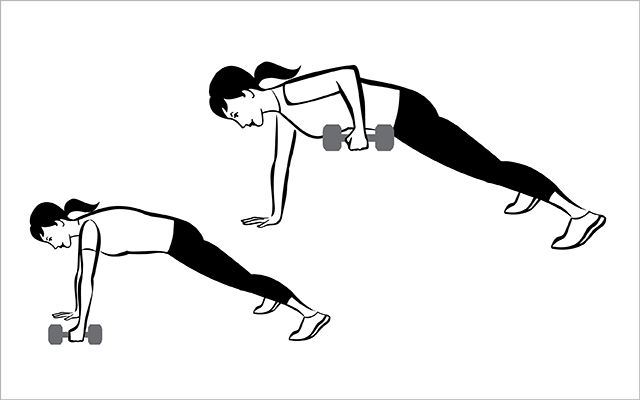

Renegade Row

Illustrations by Cindy Luu

Illustrations by Cindy Luu- Assume a wide high plank position, with your right hand planted on the floor and your left hand holding a light dumbbell.

- Keeping your core engaged and your hips and shoulders squared to the floor, pull the dumbbell off the floor. Keep your pulling elbow close to your body and draw your shoulder blades down and back.

- Reverse the movement, touching the dumbbell to the floor, and repeat for eight to 12 reps. Switch arms and repeat. (See “BREAK IT DOWN: The Renegade Row for additional form tips and techniques.)

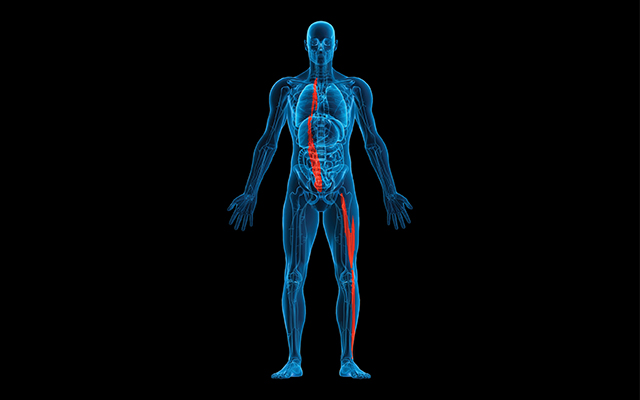

Deep Longitudinal System

This system runs vertically along your back and down your legs.

Illustrations by Paul Price

Illustrations by Paul PricePower Up

The deep longitudinal system (DLS) comprises several of your back-body muscles, including the erector spinae (the muscles that flank your lower spine), the biceps femoris (hamstrings), and the peroneus longus and tibialis anterior (two smaller muscle groups in your calf that stabilize your lower leg).

The muscles of the DLS work together in any movement that requires you to extend or straighten your hips while your feet are planted: squatting, deadlifting, lunging, and, once again, walking. “Any movement where you’re moving horizontally through space involves the DLS,” says Henkin.

Problems in the DLS often crop up with desk sitters, says Mundinger. “When you sit, you’re tighter in the front. Often, you’re not activating your extensor muscles whatsoever for eight hours a day.” Then, when you go to the gym or play sports that work your legs, problems can quickly develop.

If you have pain during or after squatting or deadlifting in the gym, says Anderson, there’s a good chance you have a hitch somewhere along your DLS.

“One quick solution is to foam roll the entire DLS,” he says, including the hamstrings, your lower back, and your calves. “Roll out each area slowly, and spend 30 to 60 seconds on any area that feels particularly tender.”

Repeat before working out, or any time you’ve been sitting for an extended period.

The Moves

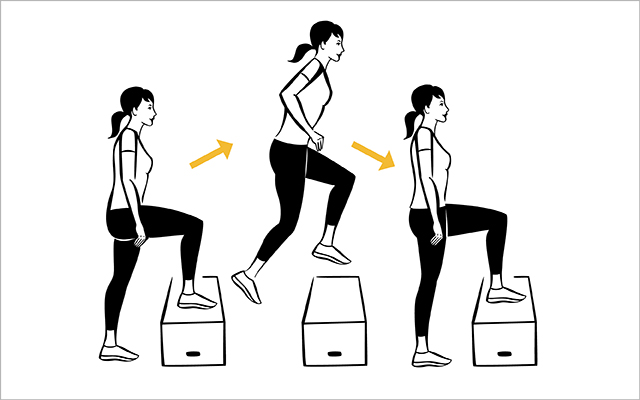

Alternating Power Step-Up

Illustrations by Cindy Luu

Illustrations by Cindy Luu- Stand behind a sturdy box. Start with a low box until you are comfortable with the movement, and work your way up to one that is about 18 inches high.

- Place your right foot on the box, and push explosively through your foot, extending your right hip completely as you jump into the air.

- In midair, switch the position of your feet.

- Land with your left foot on the box and your right foot on the floor.

- Repeat, without pausing, for eight to 12 reps.

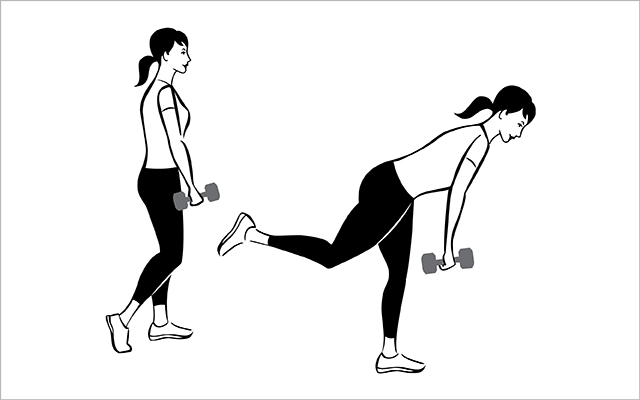

Single-Leg Romanian Deadlift

Illustrations by Cindy Luu

Illustrations by Cindy Luu- Stand upright, holding a dumbbell in your right hand.

- Shift your weight onto your left foot and lift your right foot slightly off the floor.

- Keeping your lower back in its natural arch, your hips and shoulders square to the floor, slowly hinge forward. Allow your left knee to bend slightly as you lift your right leg behind you.

- Use the hip hinge to lower the dumbbell toward the floor, keeping it close to your body throughout the movement. Do not bend at the waist: Brace your core to keep your back straight. Lower the dumbbell only as far as you can with good form; you may not reach the floor.

- Pause, reverse the movement, and repeat for up to eight reps per side, maintaining proper form. (See “BREAKT IT DOWN: The Single-Leg Deadlift” for more on this one-sided strength move.)

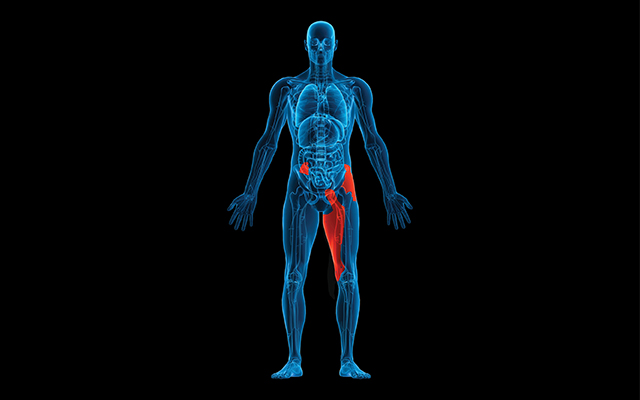

Lateral System

This group includes smaller muscles around your pelvis and groin.

Illustrations by Paul Price

Illustrations by Paul PriceFind Your Balance

The fourth major sling, the lateral system (LS), stabilizes some of the most common moves many of us take for granted: raising our arms out to the sides and overhead, stepping side to side, bending at the waist from left to right, and standing on one leg without losing balance. The motions are known collectively as frontal-plane movements and are controlled primarily by the muscles in the LS.

Compared with muscles in other sling systems, the structures of the LS are fairly small: If you’re standing on your right foot, they include the gluteus medius (outer hip) and adductors (inner thigh muscles) on your right leg, and your quadratus lumborum (a small lower-back muscle that hikes your hips up laterally, as if you were doing the cha-cha) on your left side. Stand on your left foot and everything switches around.

While these muscles are small, their function is important. Weakness in the LS is associated with poor balance, lower-back pain, and even knee pain, since LS muscles help control the direction of your knee during walking and running, which are both essentially single-leg activities.

Without your LS muscles, “you’d fall left or right whenever you stood on one foot,” says Anderson.

If people say you walk like a supermodel — hips swinging side to side as you move — you may be unstable in the frontal plane and your LS may need attention, says Mundinger.

A more precise test: “Face a mirror and stand on your right foot for 60 seconds. If your left hip drops appreciably in that time, you need to work on your lateral system,” says Anderson. (Repeat the test on the other side, too, since the sides may not be equal.)

The Moves

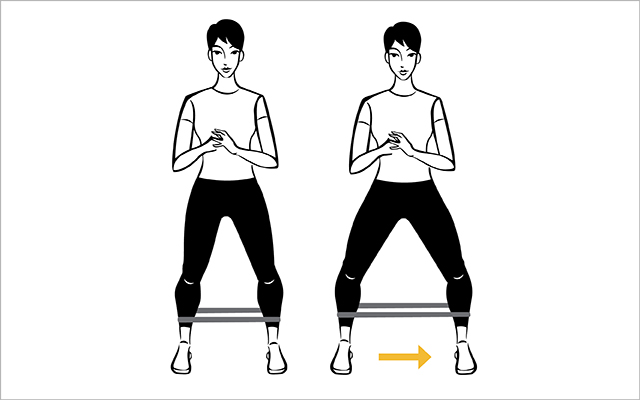

Lateral Tube Walking

Illustrations by Cindy Luu

Illustrations by Cindy Luu- Loop an exercise band around your ankles.

- Assume an athletic stance, with feet parallel, knees slightly bent, and torso upright.

- Step your left foot directly to the left and shift your weight to your left, lifting your right foot off the floor.

- Resisting the pull of the band, slowly bring your right foot toward your left and lower it to the floor.

- Repeat, stepping your right foot to the right.

- Alternate sides, performing 10 reps on each side.

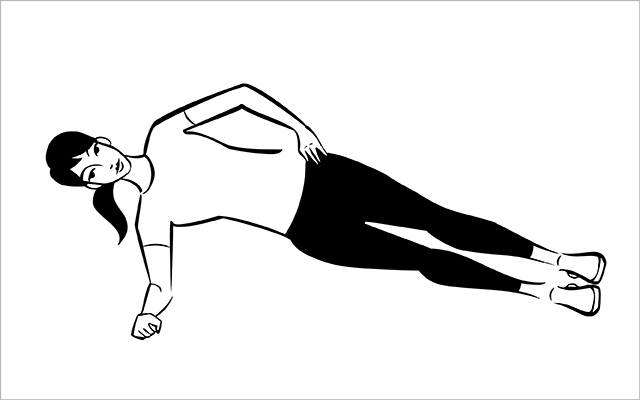

Side Plank

Illustrations by Cindy Luu

Illustrations by Cindy Luu- Lie on your right side on a firm, padded surface.

- Place your right forearm and elbow on the floor, elbow directly below your shoulder.

- Stack your left foot directly on top of your right and flex both feet. (To make this easier, stagger your feet or drop the bottom knee to the floor.)

- Press your body up so it forms a straight line from your heels to the crown of your head.

- Hold this position for 20 to 30 seconds, then switch sides.

Incorporate these moves into your regular workout routine to build strength and start moving more efficiently. No matter your health goals or athletic pursuits, knowing how your slings function can help you achieve a new level of fitness and a deeper understanding of how your body works — both in the gym and in your day-to-day life.

This originally appeared as “Made to Move” in the September 2016 print issue of Experience Life.

This Post Has 0 Comments