One of the distinguishing features of being human is our ability to stand upright and move on two feet. Our curved spine, foot structure, center of gravity, limb length, sling-system muscular organization, and complex, thinking brain are testaments to our bipedal evolution.

“Walking is a physical wonder and a feat of incredible neurological acrobatics,” says Nick Strauss-Klein, GCFP, a certified Feldenkrais practitioner based in St. Paul, Minn. “Humans have the capacity to walk for miles or even tens of miles every day.”

As a low-impact, weight-bearing cardio exercise, walking is unquestionably good for us. It’s long been touted for its fat-burning, bone-building, heart-pumping, metabolism-boosting, and anti-aging properties. Walking well and with intention also connects our bodies to our minds: It supports brain health, serves as a form of moving meditation, and can even fight depression.

So we know why walking is so great. The problem is that too many of us no longer know how to walk well.

Many Americans are sedentary, and despite the gamification of fitness through trackers and smartphone apps, a lot of us don’t actually walk a sufficient amount each day to see substantial health benefits. When we do walk, many of us actually limp, shuffle, or otherwise move our bodies around in uncomfortable ways.

Walking, for lots of people, isn’t easy or fun, isn’t contributing to overall health, and, frankly, isn’t “natural.”

But it doesn’t have to be a chore. By “relearning” how to walk — with greater ease, as our bodies are physiologically meant to move — we may find it not only easier to walk more, but that it’s also more enjoyable. Then, it becomes possible to reap the rewards that make walking so special.

Made for Walking

We have grown so accustomed to moving around on two legs that we often overlook all the advantages of our upright mobility.

“Walking allows us a fantastic dynamic instability,” explains Strauss-Klein. “By being on two feet, we are free to orient and move rapidly in any direction without hesitation or preparation, turning around our vertical axis.”

This is significantly different from the spinal position of animals who walk on four legs. Upright walking gives us a tall vantage point and a view of the horizon to search for food and threats. It also frees our hands.

“You can see that all these things create options: for distance, for movement, for situational awareness, for building and carrying and creating,” says Strauss-Klein. (For more on the mechanics of walking, see “How We Walk” below.)

Moreover, the physical act of walking has a critical impact on brain development, says Jonathan FitzGordon, a New York City–based movement specialist and the creator of CoreWalking, a holistic walking program. “When we walk well, the two sides of our body walk in consistent opposition,” challenging us physically and mentally.

We begin to develop this alter-nating, left–right, crossbody move-ment pattern as babies, and we want to keep grooving these patterns throughout our lives. “When we walk correctly, every step includes a spinal twist that works to move, massage, and activate our organs and core,” says FitzGordon. “Walking poorly leaves us stagnated energetically.”

What does “walking poorly” look and feel like?

Pain, discomfort, and extreme exertion are strong indicators that something isn’t quite right. Sometimes these are the impetuses — especially if they come on suddenly — that lead us to see a gait specialist or other practitioner. But more often than not, they are easy to ignore or miss early because the issues arise gradually.

“Once the body develops awkward movement habits, it becomes comfortable with them,” says Sherry Brourman, PT, author of Walk Yourself Well. When that happens and we get used to our hampered movement patterns — be it because of an adaptation to cope with pain or complacency with a habit — “we don’t even realize we’re not moving in the delicious, fluid ways we’re designed to,” she explains.

Walking Habits

It’s tempting to blame our modern, mostly sedentary lifestyles for these troubles — the prevalence of sitting and motorized transportation means we’re losing what we’re not using. But these factors, while important, don’t tell the whole story.

“The most influential factor for gait is the walking patterns of the immediate family,” says FitzGordon. “We learn by imitation and we tend to imitate our parents, siblings, and so on. If they have movement issues, we will likely inherit some of that pattern.”

Popular shoe choices, particularly flip-flop sandals and high-heeled shoes, also affect the way we walk. Chronic use of high heels has an especially negative impact on our natural gait. “The lift of the heel has corresponding alterations throughout the kinetic chain, especially the lower back,” explains Nathan Briner, a California-based sports therapist and creator of PostureRx, an online movement program. “Heels also distort the heel-strike and push-off phases of the gait cycle and place significantly more demand on certain muscles, while reducing workload from others.”

Large, heavy backpacks — like the ones many kids haul to school every day — also put undue stress on our bodies. “I couldn’t say that the effects are irreversible, but it certainly puts strain on the neck and back,” Briner says. “This can create what I call a movement-dominance pattern — a specific pathway of movement that a person relies on and moves from constantly.”

Deconditioning, meaning “the body doesn’t have the strength or endurance to hold itself upright or move through a complete stride,” is another common cause of shuffling or dragging gaits, especially in elderly and sedentary populations, says Briner.

“There are emotional reflections in our movement patterns,” says Brourman. Shyness, introspection, or depression are commonly expressed by hunched shoulders, which inhibit breathing; a down-turned gaze, which puts stress on the neck; or a shuffling stride, which lacks propulsion.

Gait problems may also be a manifestation of our mental states. “There are emotional reflections in our movement patterns,” says Brourman. Shyness, introspection, or depression are commonly expressed by hunched shoulders, which inhibit breathing; a down-turned gaze, which puts stress on the neck; or a shuffling stride, which lacks propulsion. Over time, these and other types of postures can make walking a chore — a potentially painful one.

The down-turned gaze and hunched shoulders are increasingly prevalent for technological reasons, too, as more people focus on the smartphones in their hands instead of the paths ahead of them.

Injuries also play a role by creating compensation patterns. “It makes perfect sense to turn out your foot and walk gingerly if you break your big toe,” says FitzGordon. “Once it heals, the goal is to return to the old pattern that uses the big toe again. Many people, however, retain some of their compensatory patterns after injuries.”

Briner agrees, explaining that “our bodies innately know to shift posture and function as a way to minimize harm when a disease state or injury is present.” Because these shifts are compensatory and, in many cases, natural, he hesitates to label them “negative.” But if they persist or no longer serve an active purpose, they can become a strain on the system.

This wide array of factors causing gait issues makes it difficult to prescribe a one-size-fits-all rehab program.

If someone is deconditioned, for instance, a general fitness plan that combines strength training — focusing on the legs and core — with a gradual increase in the amount of walking can go a long way.

On the other hand, if someone’s posture is compromised due to emotions, physical intervention may not be helpful, at least not on its own.

Finally, if someone is injured and the altered gait is a compensation, it’s important to recognize that it’s serving a purpose and should be corrected only under the guidance of a trained professional.

The one thing that can benefit everyone, our experts agree, is also the starting point for exploring your gait: paying attention.

Mindful Movement

There’s good news and bad news when it comes to improving your gait. Because your tissues remain adaptable throughout your life, your old movement habits can compound and worsen as time goes by. But those adaptable tissues also allow you to change old habits for the better.

The challenge is figuring out what’s better, says Briner.

“There is so much variation from one body to another,” he explains. “So what may be good for one body may not be good for another.”

An ideal gait is one that works best for your body in a given moment. No one who specializes in gait issues will say, “You should walk this way.” Rather, find your best way, then walk it. And expect it to change throughout your life.

“This may sound trite, but the ideal gait is one leg in front of the other with an oppositional arm swing — heel, ball, toe,” explains Briner.

But even that assumes too much similarity across human bodies: Someone with cerebral palsy might have a toe-first gait that is exactly right for him or her. Someone with a leg-length imbalance might need to strike the longer leg in a mode other than heel first.

What this tells us is that forcibly improving your gait is actually not the best way to walk better — that is, more comfortably, more efficiently, and with more joy. The first step is simply to be mindful of how you’re moving.

Pay attention to your body — your feet, knees, hips, pelvis, core, arms, neck, head — as well as your breathing and where you’re looking as you walk, says Brourman. Without consciously trying to change anything, begin to notice how your body organizes itself from the ground up. Pay attention to each piece individually and ask yourself what’s happening and what you’re experiencing: Do you feel completely natural when you’re walking, or do you feel discomfort? (For more on mindfully walking, see “The Walker’s Body Scan,” below.)

Through this body-scan method, you can avoid the perspective that gait dysfunctions are “inherently defective,” says Briner. Instead, “we can see them as windows of opportunity to learn about ourselves, to learn how the body might be trying to grab our attention, or even to learn to appreciate how our bodies can find intelligent solutions to trouble.”

If this sounds different from what you’re already doing — if it sounds difficult — that’s because it can be. “It is a ‘feeling’ game, and not everybody is up for it,” says FitzGordon.

“A lot of people who feel they can’t walk comfortably might do well to change their intention to amble instead,” suggests Strauss-Klein. “Otherwise, what they’re actually doing is imposing a kind of power walk on themselves that feels miserable.”

Strauss-Klein offers the following advice for beginning to walk mindfully: “Be creative about small and safe introductions to walking so they can be pleasurable experiments. Take short breaks at work, walk with friends, amble somewhere beautiful. Don’t start a walk by thinking about how fast, how long, or how far you’ll go, but by noticing the simple pleasures of it in any way you can.”

How We Walk

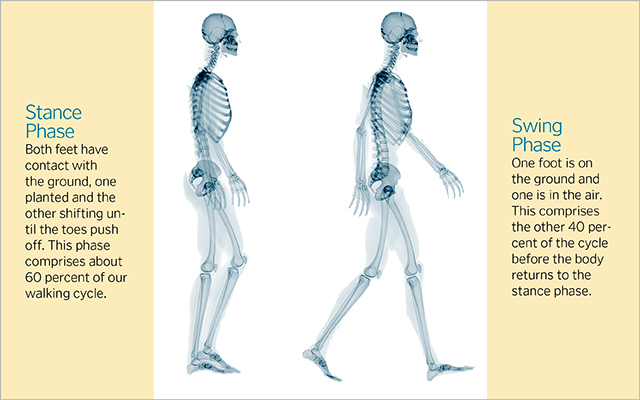

Walking, a seemingly basic and straightforward movement, is actually quite an impressive feat. The brain and body, including the musculoskeletal and visual systems, manage the movement in ways that bypass conscious awareness. This allows us to achieve a continuous state of balance — one leg supporting the body while the other leg swings through. We not only avoid falling on our faces, but we achieve this movement in a routinized way.

This is a typical gait cycle, broken into two phases:

The Walker’s Body Scan

To improve awareness while you’re walking, focus on one or two of the following cues. “This will feel unnatural when you first do it,” says Sherry Brourman, PT, author of Walk Yourself Well. Over time, “the body will start to like it, and you’ll choose to use it because it feels better.”

- Point your feet as straight ahead as possible.

- Position your feet directly under your hips. about 3 to 5 inches apart.

- Walk on the centerline of your feet. not the inside or outside.

- With each step, land with a slight knee bend, your kneecaps pointing straight forward.

- Propel yourself forward by using your glutes.

- Transfer your weight completely from one foot to the other.

- Soften your chest and allow your shoulders to broaden.

- Purposefully lengthen your arms and hands as they swing forward and backward.

- To lighten the load on your neck, tuck your chin slightly so your eyes focus about 20 feet in front of you.

- As you walk, exhale fully with each breath until you feel your belly draw in.

Download a PDF of the Walker’s Body Scan.

3 Steps to Walking Better

These no-impact, seated movements comprise a Feldenkrais lesson designed to improve your walking. With them, you will explore integral components of an upright gait: the coordination between your feet and pelvis, and their integration with your spine, torso, and head.

- Do each movement five to 10 times, or as long as it feels comfortable.

- Focus on breathing freely, making the movements light, easy, and smooth, and noticing their effect throughout your unique body.

#1

- Sit comfortably upright near the front of a simple chair. Let your feet and knees rest a bit wider apart than hip width, with both feet flat on the floor under your knees.

- Relax and notice the pressure you feel where your two sit bones rest on the chair. Is your weight even on them, or is one side heavier than the other?

- Imagine you’re sitting on a compass, with north to the front, south behind you, east to the right, and west to the left. Begin to explore a small, slow, smooth movement of your pelvis so you feel the weight of your sit bones rolling a little north and south.

- Continue and notice whether your head is moving. Let it nod comfortably up when you roll north, and down when you roll south.

- Allow your whole spine to extend and flex lightly and easily to accommodate the small pelvic movement. Does your belly push forward and lengthen when your pelvis is rolling north or south? When do you get taller, and when do you get shorter?

- Rest.

#2

- Imagine that your right foot is on a bathroom scale. Slowly lighten it (but don’t lift it) so that the “scale” would reflect a little less weight. Then gently let it rest again. Relax and repeat, breathing easily without bracing your core. Let your whole body shift softly to accommodate the weight change. Keep your head relaxed over your pelvis, but free to nod, tilt, or turn a little.

- Continue with the right foot. Can you feel the weight on your sit bones shifting? When you lighten your right foot, can you allow your pelvis to roll a little toward it, to the northeast? Rest.

- Repeat on the other side by lightening the left foot. Where does your pelvis roll? What happens to the weight of your right foot? Rest.

- Now gently press your left foot into the “scale,” adding a few pounds of pressure, then release. Allow your pelvis to roll a little to the southeast. Rest.

- Repeat on the right side. Where does your pelvis roll? What happens to the weight of your left foot?

- Rest. Do you sit or breathe differently or more comfortably than usual?

#3

- Still imagining your feet on a scale, slowly alternate lightening and pressing your left foot. Breathe, relax, let your body bend and move freely, and keep your head above your pelvis. Feel the weight of your sit bones traveling along a diagonal line between northwest and southeast. Smooth out the motion and try to make it a straight line.

- Rest, then try the same thing with your right foot, your pelvis traveling between northeast and southwest.

- Playfully experiment with both feet, pressing one while lightening the other. Can you use the alternating pressure to roll your pelvis along an east–west (right-to-left) line?

- Rest. Now alternate a different way: First lighten one foot and let it rest, then lighten the other. It will feel like a slow-motion walk in which your feet never leave the ground.

- Make this simpler, a little faster, and more playful. How freely and comfortably can you let your whole body shift to enjoy each “footstep”?

- Rest, then stand up. Notice your posture, how your weight rests on your feet, and how your body is supporting itself. How is your breathing and overall comfort in standing compared with the usual?

Complete this lesson by walking quietly around the room, noticing the differences in how you feel and how you move. Pay attention — you may be aware of new sensations and a different quality of movement for the next few hours or even days.

For a guided audio recording of this three-step lesson, visit http://bit.ly/2jZ6cKG.

This originally appeared as “Walk Your Way” in the April 2017 print issue of Experience Life.

This Post Has 2 Comments

This is very informative for beginers as well as a regular for their corrective action while they are in action.

Thank you for this refresher on walking correctly. Experiencing a very long recovery from a total knee replacement and this is just what I needed today as I learn to walk again with a new knee and a pokey quad muscle. :)