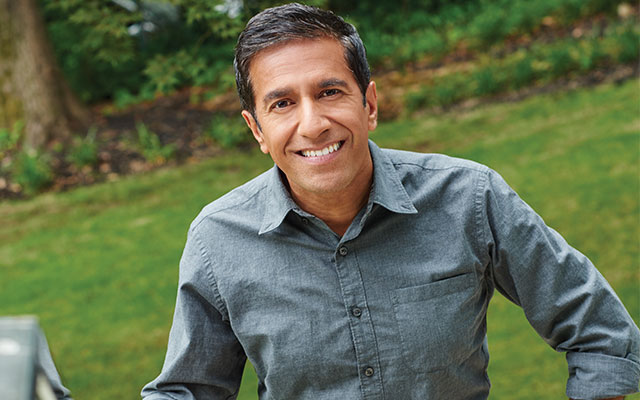

Sanjay Gupta, MD, can tell you stories. Like about the time he was embedded in the U.S. Navy’s Devil Docs elite medical unit in Iraq and performed brain surgery — with a Black + Decker drill — on a wounded Marine. Or when he was covering the earthquake-relief effort in Haiti and was summoned to a U.S. Navy ship to remove cement shards from the brain of a Haitian girl. As Gupta has said, “I’m a reporter, but a doctor first.”

Indeed, the celebrated CNN medical correspondent and neurosurgeon didn’t set out to be a journalist. He was drawn to a career in medicine as a teenager and went on to graduate from the University of Michigan Medical School.

It was during his residency that Gupta turned the page to a new chapter. Selected for a White House fellowship in 1997, he worked as a speechwriter, blending his passion for writing and storytelling with his broad knowledge of medicine and health policy. Four years later, convinced he could use the media to educate, he joined CNN. His influence has grown so widely that the Obama administration floated his name as a possibility for Surgeon General in 2009.

The seemingly disparate roles of journalist and doctor are simply “two ends of the same spectrum,” Gupta says. “I’m taking care of patients in both roles. I’m educating them about science and medicine through the media, and I’m caring for individuals in my medical practice.”

Whether he’s talking through a care plan with a patient or attending a summit about stem-cell research at the Vatican, Gupta believes storytelling is good medicine. “Stories,” he says, “are the things that people remember the most.”

Q&A With Sanjay Gupta

Experience Life | What made you decide to become a neurosurgeon and then work in the media?

Sanjay Gupta | I decided to become a doctor at 16 and got accepted into medical school out of high school. The decision to do neurosurgery came after my grandfather had a stroke. I watched the doctors, some of whom were neurosurgeons, care for him and became interested in the brain. It’s been a 30-year love affair.

I’ve also always enjoyed writing, and much of the writing I did in college revolved around health policy. After medical school, I worked as a White House fellow, primarily writing health-policy speeches for First Lady Hillary Clinton and President Bill Clinton. That’s when I realized the power of the media for sharing messages.

EL | How has working in the media influenced your medical practice?

SG | When I started at CNN, I thought I’d be commenting on health policy. Then 9/11 happened and the world changed. Suddenly I was reporting from New York, Afghanistan, and Iraq. It wasn’t at all what I expected, but I’d always been fascinated by stories of how people are cared for in the middle of war.

Unlike a few decades ago, doctors today often don’t get a chance to hear their patient’s story, so the person simply becomes “the guy with the L5-S1 disc in room 12.” I don’t do that. It’s important for me to know the details of what happened to people, so when I interact with them later, I can say, “So it was on that fly-fishing trip when you were casting and your boots got stuck in the mud that you herniated your lumbar disc.”

I learned as a kid that if you wrap something around a story, you’re going to remember it more. Journalism has helped me incorporate that in a really meaningful way into my medical practice.

EL | What are some of the biggest changes you’ve seen in medicine?

SG | When I started as a correspondent, the general sentiment of many people — and among the medical community — was that people shouldn’t be getting their medical information from places other than a doctor’s office.

But rather than assuming everything was garbage, it was clear to me and many others that we needed to roll up our sleeves and ensure the information was of the highest quality. Further, people have become more autonomous than ever, and they want to be — and should be — in control when it comes to their health. They ought to be able to learn as much as they can in a responsible way.

There’s more data available than ever before. Some is really good; some isn’t. But thanks to technology, we’ve been able to do something with all the information that the standardized medical system couldn’t, and that’s to start personalizing care for people.

EL | How is personalization changing healthcare?

SG | Right now we have a shotgun approach to most medical care. We make recommendations based on studies of several thousand people who had moderately good results. What we really need to ask is “What is the best thing for each individual?” instead of “What is the best thing for thousands of people?” That’s hard to do, but with technological advancements, we can do it better than ever.

We can know more about you than anybody else — your likes, dislikes, stressors, when your heart rate increases, how many steps you take, and what medications don’t work for you. Using FaceTime, we can connect you with a nutritionist in Thailand if he or she is an expert in the right diet for you.

In the future, telemedicine visits will ensure we won’t have to take time off work or wait three weeks to be seen by a physician. We’ll also be monitored in noninvasive ways — not just by wearable trackers, but by things present in our environment that will allow us to predict a pending medical crisis or alert us when our health is not optimal.

These tools will tell us when we need to take a walk or spend time being mindful. We’ll know that Tuesday mornings are our most productive, so we can schedule our most important projects on Tuesday morning. It’s exciting!

EL | What do you see as the future of health?

SG | A few key areas show promise. Immunotherapy — the idea of harnessing the immune system to tackle various diseases — is happening. For example, former President Jimmy Carter’s stage-four melanoma was treated successfully, in part, with an immunotherapy drug. That type of cancer used to be a death sentence, but today he’s out building houses!

Stem-cell research is another area. Some of the data being presented for treating joint pain and autoimmune diseases, including autism, is pretty remarkable.

Finally, we now know how to map and analyze the human genome, and we’re going to learn more about the mutations that drive disease and be able to treat them at their core.

EL | What’s your prescription for living a healthy life?

SG | I believe learning to care for yourself and your family has to be part of a daily conversation. It can simply be spending a little time every day thinking, “How am I going to move today?” or “Where am I going to get nutritious food?” or “How can I be better today compared with yesterday?” Do a little bit every day, and you’ll be amazed by how much you grow and learn, and how much healthier you become.

Photography by Kwaku Alston

This Post Has 0 Comments