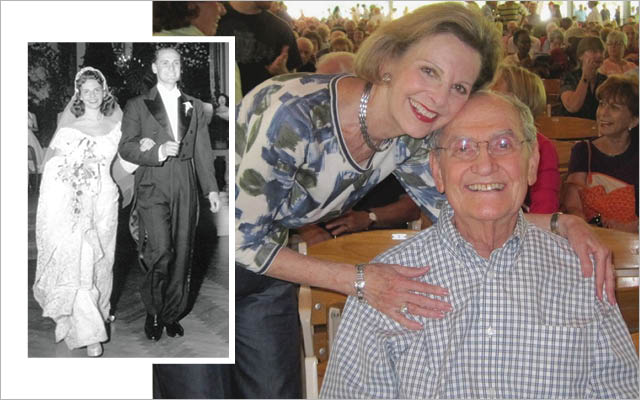

When you’re married for 50 years, you know the strengths and weaknesses of your spouse. Throughout our marriage, my husband, Ady, was the smartest and most responsible person I had ever met. If I asked for his help and he agreed, I checked that task off my list as complete.

So, when Ady began to lose function — forgetting to check out of a hotel, for instance — my discomfort was huge. This atypical behavior became repetitive.

Ady was keenly aware of the slippage and went willingly to see the appropriate doctors. Over several months we received many varying opinions. Finally, in October 2005, we got the appointment we were waiting for with Ranjan Duara, MD, medical director of the Wien Center for Alzheimer’s Disease and Memory Disorders at Mount Sinai Medical Center in Miami.

After a series of tests, Dr. Duara uttered the dreaded words: “You have Alzheimer’s.” I listened in horror as my gentle, accomplished husband said flatly, “I don’t want to live anymore.”

Ady was about to retire as a home builder. Our children were well established in their careers and each of our four grandchildren seemed solid and full of potential. We had hoped to have the leisure time to travel and enjoy each other. Now three words had changed everything.

Shortly after his diagnosis, I sat in a drab waiting room at the Wien Center. Ady was about to participate in a study, and I was tasked with filling out voluminous forms.

Most of the questions related to my husband’s abilities, but the final two pages were addressed to me as the caregiver. The first question was, “How many times a week do you feel happy?” My answer was immediate: “Every day.” The next question: “How many times a week do you feel sad?” Again, my immediate answer: “Every day.”

There it was in black and white. How can you be married to a man since you were 19 and not feel an almost constant sadness when you see him slipping away from you?

It was then that I began to understand my dual mission. The first was about Ady: to do everything in my power to slow the process of decline and give my husband the greatest fullness of life. At the same time, I had to seek joy every day. Letting the sadness quotient win would not be good for me, and it certainly would not be good for Ady.

The difference was this: All my life, that joy had come naturally. Now I had to seek it.

The Power of Attitude

During the first year, Ady began to show the typical Alzheimer’s signs: stubbornness, frustration, irritability, rigidity — but fortunately, never violence. Within a year, however, he became known as the man with a radiant smile.

I was totally unprepared for this caregiver role, as I believe we all are, so I read books on Alzheimer’s in an attempt to better understand: How do I give him the best life possible? How do I bolster myself to be up to the challenge that faces me?

I also kept in mind a quote from author, psychiatrist, and concentration-camp survivor Viktor Frankl, MD, PhD, who wrote in Man’s Search for Meaning that the thing no one can take away is the right “to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances.”

Yes, Ady’s memory was slipping, but I found that his emotional sensitivity was greatly heightened. He reacted with uncanny awareness to the slightest hint of disappointment in me.

Alzheimer’s patients tend to ask the same question over and over as they forget the answer a few minutes later. By the fourth or fifth time, most of us react with an intake of breath or some nonverbal expression of frustration, implying “I’ve told you that a hundred times.”

What I came to realize in the six years of caring for Ady was that the attitude I chose to bring could either diminish, demean, and agitate, or bring support, contentment, and dignity. Our actions, our attitude, our frustration, or our support as caregivers have a powerful effect on our loved ones.

The Importance of an Active Mind

Together, Ady and I mapped out a plan to keep his mind active virtually every waking minute. This detailed daily schedule lowered his anxiety because he knew what was happening next.

At first, our goals focused on his physical health and a daily exercise regimen, which included swimming and riding a stationary bike. Equally important, I also strove to foster creativity and encourage old talents or interests. For example, Ady had never drawn a picture in his life. One night after dinner I put a pad, crayons, markers, and colored pencils on the dining-room table and asked him to draw something.

After getting over the shock of the request, he picked up a marker and began to draw — it became a nightly activity for his expression of joy. He was so proud that he signed and dated each one.

He loved classical music and returned to the piano, playing Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms, for an hour each day. One night, he wrote me a brief letter of thanks and love. My appreciation was so enthusiastic that he made it an almost nightly habit.

Along with many other joyful activities, every car trip to a concert or appointment became a time for singing all his favorite show tunes or college songs from Dartmouth — and for me to say what I did not want left unsaid.

All of these actions resulted in improvements in Ady’s health — and the rare regeneration. At an appointment in late 2010, based on both test results and his personal observations, Dr. Duara confirmed that Ady was making positive strides.

In March 2011, we took eight couples of close friends out to dinner as a thank you for their support. Without my telling Ady in advance who was coming, because I did not want to put pressure on him to remember their names, he greeted every guest by name. Then, seated at the table, he welcomed the group with a spontaneous, loving, and coherent toast of appreciation.

As we were leaving the restaurant, two of our close friends asked the same question: “Are you sure Ady has Alzheimer’s?”

Taking Care of Yourself

For the first three-and-a-half years after Ady’s diagnosis, I had no additional help other than our housekeeper, Lizette. After Ady fell and fractured his hip, Lizette became his chief caregiver. That support allowed me to run errands and have a little time for myself.

After Ady’s hip surgery and rehabilitation, he never walked on his own again, so I had no choice but to bring in an aide. In retrospect, not getting extra help sooner was a mistake: Ady made the most progress after I had some relief.

After a break for activity, I returned ready to give my all. I realized that I could not stop living my life. It would not have been good for me, and it would certainly not have been good for Ady.

One cannot be on 24/7 without a respite. When one feels trapped, a host of other negative qualities and unhealthy emotions (resentment, anger, impatience, and irritability) begin to creep in. If you need help, it needn’t be a licensed aide; even a family member, friend, or neighbor to play cards or chess with Ady was valuable.

Ady was extremely supportive, but what worked for me early on was an honest, open expression of why taking time for a walk, or to be with friends, enabled me to be there for him more fully.

I continued to play tennis and go to aerobics classes. As valuable as exercise was for Ady, it was equally essential for me as the caregiver.

A superb psychiatrist, Ellen Rees, MD, who I turned to for assistance with Ady, helped me cope with the changes in my life in a realistic and constructive way. She encouraged me to be in touch with my emotions, seek time alone, and grieve for the loss I was living through.

Our son also reminded me to get enough sleep, giving me a curfew to turn off my computer at 9 p.m. It helped to spend time with friends and people who saw humor in life; it gave me a new awareness of the healing power of laughter.

Dr. Rees also encouraged me to keep a journal, and I found that my insights came at the most unexpected times. At first, writing my thoughts down was simply a tool to remind myself of what worked and what did not, but eventually it led me to collect these ideas into a book, Choosing Joy Alzheimer’s: A Book of Hope.

Finding a Way Forward

Ady’s loss after 55-plus years together was totally unexpected. The morning after our dinner with friends, on March 25, 2011, Ady did not awake.

As I’ve mourned and processed my grief, it has become clearer to me that my love for Ady during those six years not only did not diminish, it actually grew. I had such great respect for the way he handled his condition and accepted all the changes in his life; for his smile, his cooperation, his concern about me, and his daily encouragement that I live fully.

On a beautiful fall morning a year and a half after Ady passed away, I was at Kripalu Center for Yoga and Health in the Berkshires for a weekend meditation retreat. We were learning how to do a slow meditation walk; we removed our shoes and walked barefoot in the grass toward a spectacular view of the Stockbridge Bowl.

I walked alone, surrounded by the indescribable beauty of the lake, the unique pungent aroma of the fall air, the vivid, glowing rusts and reds and yellows of the leaves. And then the flood of tears began. Uncontrollable tears, wrenching tears.

I was struck with a life-changing insight that is still with me: I suddenly understood that these were not tears of sadness, but tears of joy and gratitude for the blessed life that I had lived and shared with a kind, gentle, pure, giving man.

Whatever I had achieved in life was far surpassed by the rewards of ensuring quality of life for the man who I loved until his last breath. I knew beyond doubt in that moment that if I had my life to live over again, I would make the same choices.

Helene’s Top 3 Success Strategies

- Give it your all. Instead of passively watching a loved one decline, strive to make every moment you still have together as good as possible for as long as possible. Our actions and attitudes can and do make a difference.

- Take care of yourself. It is vital that you understand what you need. You are not helping your loved one if you stop living. If you feel trapped, negative emotions begin to creep in. Give yourself a little relief each day.

- Keep a guiding principle to enhance both your lives. The more we treat our loved one with patience, kindness, support, compassion, respect, and love, the more we can allow those we care about to preserve their dignity.

Tell Us Your Story: Have a transformational healthy-living tale of your own? Share it with us at ELmag.com/myturnaround.

This Post Has 0 Comments