You may have heard the term “functional training” tossed around at the gym, and you may think you’ve got a handle on it: It’s a type of athletic conditioning that uses balls, bands, kettlebells and other tools to strengthen “stabilizing muscles” that traditional strength-training exercises miss. Right?

Not exactly. Or at least, that’s not the full story.

“When people think of functional training, they think of bands, gadgets and gimmicks,” says Michael Boyle, author of Functional Training for Sports: Superior Conditioning for Today’s Athlete.

“While those are some of the tools used within the system, they are not the system itself. The simplest definition of functional training is that it’s the application of functional anatomy to training.”

In other words, it’s resistance and flexibility training that’s based on how the body works. It’s more than just a means for the fitness elite to enhance performance and reduce injury risk — it also improves the general health of the musculoskeletal system and enhances performance in everyday activities.

The methods commonly associated with functional training are secondary to the set of principles upon which it is based. These principles can be reduced to three basic rules:

Rule 1: Train movements, not muscles.

Your muscles never work in isolation in sports. Instead, many muscles cooperate to execute specific movement patterns. Your strength workouts should involve similar patterns.

Rule 2: Training should be sport-specific.

Different sports and activities emphasize different movements. The specific movements you use in functional training should simulate those you use outside the gym. If you’re a softball player, for example, you’ll want to emphasize shoulder and torso rotation along with other movements involved in throwing a ball and swinging a bat.

Rule 3: Train progressively.

Functional training is often associated with exotic movements, such as performing squats while balancing on a Swiss ball. But when practiced correctly, functional training begins with basic movements designed to address major weaknesses and progresses toward more advanced, sport-specific actions. Basic modes of movement progression include:

Single plane > Multiplanar

Isometric > Dynamic

Slow > Fast

Nonresisted > Resisted

Whatever Works

Though functional training is not defined by any particular method, there are certain training methods it frequently employs — because they work.

- Single- and Alternating-Limb Movements: Traditional strength exercises such as the machine leg extension and the barbell biceps curl involve moving both legs or both arms together. But because single- and alternating-limb movements — think running — are more common in sports and everyday activities, they are also more common in functional training.

- Multiplanar Movements: Most traditional strength exercises are done in the sagittal plane (forward andbackward movement), but real-world body movements are often multiplanar — including frontal (side-to-side) and transverse (rotational) planes, explains Lee Burton, PhD, ATC, CSCS, program director for athletic training at Averett University in Danville, Va. “In functional training,” Burton says, “we try to break people out of this sagittal-dominant way of training.”

- Balance Elements: Unlike most sports movements and everyday activities, there is no balance requirement in traditional strength exercises (like the bench press). In contrast, functional training makes frequent use of exercises with a balance component, such as the single-leg dead lift. (See “How to Build Your Balance“.)

- Core Training: “In every movement, some parts of your body need to be stable and other parts need to be mobile,” says Burton. Many people have inadequate stability in the hips, pelvis and lower spine because they cannot properly activate important stabilizing muscles such as the deep abdominals. Functional training relies heavily on core-strengthening exercises to teach the neuromuscular system to properly activate these muscles while performing alternating-limb movements.

- Variable Speed: Most people perform traditional strength exercises at the same slow speed. But sports movements often involve high-speed muscle action, so functional training incorporates high-speed exercises such as the single-leg box jump.

The Catch

There is one caveat to functional training:

Doing it effectively requires some specialized knowledge — and practice. Burton suggests that beginners work with trainers who have specific education, certification and experience in functional training. The more specific a trainer’s experience to your sport or special needs, the better.

Functional Exercises for Soccer

Brijesh Patel, head strength and conditioning coach at Quinnipiac University in Hamden, Conn., recommends these two functional exercises for soccer players:

Split Squat Hold:

- Begin in a normal standing position. Take a big step forward into a lunge and hold the bottom position with your back knee just barely above the floor. Your front thigh should be parallel to the floor, your front shin perpendicular to the floor and your weight on the ball of your front foot.

- Attempt to pull the ground back with the front leg and relax the back leg as much as you can by squeezing the glutes of the back leg.

- Now hold it.

- Patel suggests you begin with three sets of 30 seconds on each leg and add 10 seconds each week until you can hold for one minute.

Sled Push:

- Place a 25-pound or 45-pound weight plate on a towel on the floor.

- Bend down and put both hands on top of it, then push it forward as fast as you can.

- Push the weight for a total of 100 to 200 yards, broken down into smaller segments based on the amount of floor space available.

Functional Exercises for Golf

Paul Chek, the founder of the C.H.E.K Institute in Vista, Calif., and author of The Golf Biomechanics Manual, recommends the following pair of functional exercises for golfers:

Shoulder-Spine Integrator:

- Lie on your right side with your knees bent 90 degrees, your right arm extended palm up on the floor and a rolled towel or pillow under your head.

- Bend your left arm and place your left palm on your forehead.

- Gently rotate your neck as far to the left as possible, keeping your palm in contact with your forehead.

- Return to the starting position and repeat 10 to 20 times, then reverse your position and perform another 10 to 20 repetitions.

- Do one to three sets.

Supine Lateral Ball Roll:

- Prop yourself face up on an exercise ball, your head and upper back supported by the ball, feet placed flat on the floor slightly more than shoulder-width apart and knees bent 90 degrees.

- Lift your hips so your trunk is parallel to the ground.

- Extend your arms out to either side and balance a dowel rod (or broomstick) across your chest.

- By shuffling your feet, slowly roll the ball to your right until only your left shoulder blade is supported by the ball. Tighten your core so the alignment of your body doesn’t change (your trunk remains flat like a tabletop).

- Pause and hold for five to 10 seconds and then roll to the left until only your right shoulder blade is supported, and hold for five to 10 seconds.

- Roll six to eight times to each side. Do one to three sets.

Functional Exercises for Triathlon

Gary Bredehoft, CSCS, a USA Triathlon–certified coach and owner of Tiger Coaching and Personal Training in Lincoln, Neb., uses these three exercises with his triathlete clients:

Swim Stretch-Cord Half-Pull:

- Affix a stretch cord with handles to a sturdy base at waist height and stand facing it.

- Bend forward 90 degrees from the hips, and extend your arms straight ahead with a handle in each hand, palms flat, with slight tension on the cords.

- Bending your arms to 90 degrees, pull your forearms down and toward you, keeping your elbows high and pointing slightly outward.

- Stop when you can’t comfortably move your forearms farther; ideally, your fingertips will be pointing down. (For an explanatory picture, see www.byrn.org/gtips/swimcords.htm/.)

- Return to the starting position and repeat.

- Continue for one minute. Complete one to three sets.

Exercise-Ball Leg Curl:

- Lie face up and place your heels together on top of a stability ball.

- Raise your pelvis so that your body forms a straight plank from head to heels.

- Contract your buttocks and hamstrings and roll the ball toward your buttocks.

- Pause briefly and return to the start position.

- Focus on keeping your pelvis from sagging toward the floor throughout this movement.

- Do eight to 12 repetitions per set and one to three total sets.

If you’re up for an even greater challenge, do a single-leg stability-ball leg curl. Elevate your left leg above the ball and keep it straight while using the right foot to roll the ball. Complete one to three sets of eight to 12 repetitions with each leg.

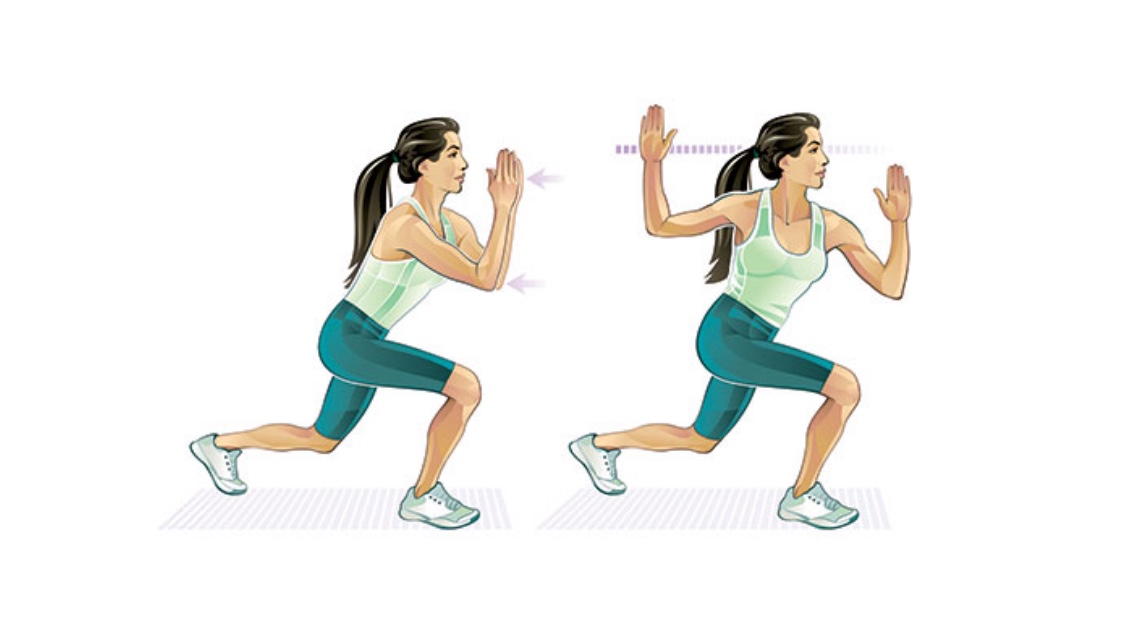

Step-Up With Leg Drive:

- Stand facing a sturdy box or stacked aerobics steps at least 12 inches high.

- Step onto the box with your right foot. If the height is right, your right thigh should be parallel to the ground.

- Extend your right hip and knee so that you are now standing on the box.

- As your body rises, drive your left leg forward and pump your right arm as you do when running, but with exaggerated force.

- Step back down with your left foot first and then the right.

- Repeat 15 times, rest for 30 seconds, and then perform 15 more step-ups with your left leg.

This article originally appeared as “Join the Movement.”

This Post Has 0 Comments