Summer might be over, but don’t let your waistline go to the dogs just yet. Looking good at the beach isn’t the only reason to flatten our tummies. Recent studies in fat distribution are giving us an even more pressing incentive to reduce our rounding stomachs: our health.

It turns out that abdominal fat (more so than fat in other areas of the body) has a major impact on whether we stay healthy and vital or put ourselves at increased risk for several chronic diseases.

First off, we’re not talking about your typical tummy fat, so don’t fret about a little paunch. All of us need a bit of internal belly fat, says nutritional expert Pamela Peeke, MD, MPH. “We need stomach fat to help cushion organs, maintain internal body temperature, and it’s also a good source of backup fuel,” says Peeke, author of Body for Life for Women: A Woman’s Plan for Physical and Mental Transformation and Fight Fat After Forty.

The problem is that not all abdominal fat is created equal. It is the type of belly fat – and the places it’s located – that determine whether it’s likely to lead to health problems.

Two Types of Fat

Ringing all our midsections are two different kinds of fat: subcutaneous and visceral.

Subcutaneous, which means “under the skin,” is the fat we can see and pinch – the jiggly stuff most of us lament in our bathroom mirrors. But, surprisingly, we need to worry less about subcutaneous fat than we do the visceral stuff.

Visceral, which means “pertaining to the soft organs in the abdomen,” is the fat stored deep in our abdomens around the intestines, kidneys, pancreas and liver. This is the stuff that tends to make our tummies protrude in classic “beer belly” fashion.

While visceral fat and subcutaneous fat look much the same from a surgeon’s point of view (they have the same consistency and yellowish color), they look different under a microscope, and they function very differently on a biological level.

Subcutaneous fat is often described as a “passive” fat because it functions primarily as a storage repository. It requires a fair bit of metabolic intervention from other body systems and glands in order to be processed for energy. Visceral fat, by contrast, is considered very “active” because it functions much like a gland itself: It is programmed to break down and release fatty acids and other hormonal substances that are then directly metabolized by the liver.

When the fatty acids that are produced in our abdominal organs go directly to the liver, it “produces an unfavorable metabolic environment and triggers the liver to do all sorts of bad things,” says health expert Marie Savard, MD, author, with Carol Svec, of the recent book The Body Shape Solution to Weight Loss and Wellness: The Apples and Pears Approach to Losing Weight, Living Longer and Feeling Healthier. “Excess visceral fat can lead to increased blood sugar and higher insulin levels, and it also generates increased inflammation, all of which are the perfect set-up for diabetes, certain types of cancers and stroke.”

Abdominal obesity is a key risk factor for insulin resistance and “metabolic syndrome.” The chronic inflammation that results from excessive visceral fat has also been linked to heart disease, and a recent Kaiser Permanente study of 6,700 participants showed that people with higher rates of abdominal fat are 145 percent more likely to develop dementia.

Visceral fat may be located in our abdomens, Peeke says, but it can wreak all sorts of damage that goes far beyond our bellies. “No other fat in the body does that,” she says. Which is precisely why we need to keep the amount of fat in our abdomens under control.

When we don’t, the result may be a belly that’s literally packed with fat, a phenomenon that can lead to a surprisingly solid protrusion – one with deceptively little pinchable fat on the surface.

Carrying excess visceral fat “is like trying to pack 7 to 10 pounds of potatoes in a 5-pound bag,” says Silver Spring, Md.–based bariatric surgeon Gary C. Harrington, MD. “There’s no more room for things to grow in there, so it becomes very tight.”

What Causes a Potbelly?

So why is it that some of us tend to gain weight in our midsections? There is no single answer. Instead, the calculus behind the appearance of a potbelly involves four factors: genetics, eating habits, stress and hormones.

Genetics

The first part of the equation is the genetics of body shape. Some of us, says Savard, are just destined to be “apples,” with an inclination to gain weight in the stomach and upper-body region, while others are fated to be “pears,” who gain weight in their hips, buttocks, thighs and lower legs. According to Savard, it all comes down to your waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), which is the division of your waist measurement by your hip measurement. (For an accurate WHR measurement, relax your abdomen and measure at the navel and around the bony part of the hips.)

If you’re a woman whose WHR is 0.80 or lower, you are pear shaped; if your WHR is higher than 0.80, you’re apple shaped. For men (who, for the most part, are apple shaped, since they are more inclined to store visceral fat), the cutoff is 0.90 instead of 0.80.

Many experts now agree that WHR is a better indicator than body mass index (BMI) when it comes to determining someone’s disease risk. Even apples who are currently slender and have a low BMI, Savard says, could be at increased risk for disease later in life.

“If you’re a string bean with no obvious potbelly, but your waist-to-hip ratio is more than 0.80, you will tend to have more health problems than pear-shaped people if you gain weight,” she says. When WHR is greater than 1.0 in men or 0.90 in women, health experts may diagnose the condition as “central obesity.”

Eating habits

Abdominal fat, like all fat, is produced when we ingest more caloric energy than our bodies can use. And our bodies were simply never designed to withstand such easy access to the kinds of calorie-dense foods available to us today.

“It’s certainly no secret that the way we eat is out of sync with our body’s needs,” writes Floyd H. Chilton, PhD, in Inflammation Nation: The First Clinically Proven Eating Plan to End Our Nation’s Secret Epidemic. “Most of the evolutionary forces that shaped our genetic development were exerted over ten thousand years ago when we were hunter-gatherers. Nothing in that programming could have prepared us for the Big Mac. Our bodies, and more specifically our genetics, simply aren’t designed to eat the ‘foods of affluence’ available to a twentieth-century urban dweller.”

Visceral fat was simply never a problem years ago, says Savard. Take the Pima Indians of Arizona, she says, who have prototypically apple-shaped bodies. Because the Pima Indians evolved during alternating periods of feast and famine, they developed what researchers call a “thrifty gene,” which allowed them to store visceral fat during plentiful times and use it during lean times.

Living and eating as they did traditionally, subsisting on foods they hunted, gathered or raised themselves, the Pima tended to be slender. Today, however, most are extremely overweight and suffer a 50 percent rate of diabetes among adults (95 percent of those people are overweight). “Now, with an unlimited supply of food and a more sedentary lifestyle,” says Savard, “the problem of visceral fat is not going away.”

Food today is not just more accessible, it has been reincarnated in so many heavily processed forms that we are often eating things that our bodies do not recognize as food. Our metabolism is still hardwired to process the hunter-gatherer diet of yore, and when it encounters sugary sodas and snacks that were created in a laboratory and not in a field, it is not able to process or use them efficiently. Instead, our bodies are forced to sock away that stored energy in places – like our midsections – where it does more harm than good.

Potbellies, also known as “beer bellies,” are often associated with drinking. But “beer does not promote weight or waist gain any more than any other source of calories,” says Meir Stampfer, MD, professor of nutrition and epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health. In fact, a 2003 study of 2,000 men and women from the Czech Republic, where people consume more beer per person than in any other country in the world, found no link between the amount of beer a person drinks and the size of his or her stomach. That said, alcoholic beverages are an often-overlooked, carb-dense source of calories in many people’s diets. Alcohol is processed much like a sugar in the body, and because it puts an additional strain on the liver, it may undermine the body’s fat-processing abilities.

Stress

Stress is another major reason some of us tend to pack on excess abdominal fat. As Peeke puts it, when it comes to weight gain, “genetics may load the gun, but environment pulls the trigger.” Peeke, who spent years researching the link between stress and fat at the National Institutes of Health, says that experiencing chronic stress is not only toxic for our bodies but can also beget an expansive waistline.

All of us may experience what Peeke terms “annoying but livable” stress like traffic jams and long lines at the supermarket, but chronic stress resulting from, say, a bad marriage, an illness or career challenges can actually trigger our bodies to produce high levels of cortisol, which, among other things, gives us an intense appetite that causes us to overeat. Even worse, Peeke points out, the weight we gain as a result of sustained cortisol production tends to settle mainly in our abdomens.

Hormones

Declining sex hormones is another key reason why both men and women start to develop a paunch as they age. Even pear-shaped women, whose body chemistry is mostly governed by estrogen, start to lose their estrogen advantage after menopause and are exposed to increased health risks, says Savard. “When they gain weight after menopause, the tendency is to put on visceral fat,” she says. And if they accumulate enough visceral fat, their body shape “can transform from pear into apple.”

How to Get Rid of a Potbelly

Whatever the reason, potbellies, it seems, have become something of an epidemic. The bad news is there is no quick-fix approach to tackling abdominal fat. As with other areas of the body, it’s impossible to target just one region for weight loss.

For example, commonly attempted spot remedies like crunches might tone your back and abdominal muscles, but they will do nothing for the fat stored in your belly. For that, you need to reduce your body’s store of fat overall.

But don’t be tempted by the bevy of crash diets out there either, says Savard, because you may very well end up gaining more weight. “Reducing your caloric intake by more than 25 percent simply triggers your metabolism to go into starvation mode, which lowers your [resting metabolic] rate,” she says. (For more on why cutting calories doesn’t work, see “Why Diets Don’t Work — and Never Have“.) Sticking with a sensible, whole-foods diet and moderate, daily exercise will deliver much better results.

The great news is that visceral fat, while it may be stored deep down in your belly, is often the first type of fat to burn off. The fact that this fat is metabolically active actually works in your favor once you decide to get rid of it.

Forget how much you weigh, says Savard. Losing just 2 inches from your waistline can significantly decrease your risk of a host of illnesses and diseases. “Throw away your weight scale, because health is in inches, not pounds,” she emphasizes.

Eating well and exercising regularly, including lifting weights, are key to improving your chances of losing those 2 inches of visceral weight and keeping them off. Experts suggest low-to-moderate-intensity, long-duration workouts (30 minutes or more) most days of the week.

Also key to losing visceral fat is to ingest – and not avoid – crucial fat-burning fats like omega-3 fatty acids. (Use this guide to help you understand omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids.)

“I tell people to think of the three Fs: fiber, fat and fitness,” Savard says. “It’s pretty simple, actually: If everything you’re eating is either high in fiber or a good fat, you’re eating healthy food, because there should be little or no refined carbohydrates or unhealthy saturated fats. You don’t have to worry about protein while using this approach, either,” she says, “because if you are eating healthy fats, that means you’re eating fish and nuts and keeping red meat to a minimum.”

Exercise and nutrition – especially eating small, well-balanced meals every three to four hours – is very important, says Peeke, but just as significant is learning how to manage stress levels. “I’ve always looked at the mind in addition to the mouth and the muscle,” she says.

To start down the path of stress-resilience, Peeke offers several tips, such as creating a support system, tapping into your spirituality, learning to find humor in everyday things, and finding some private space and time to record uncensored thoughts into a journal.

Upon adopting such recommended nutrition, exercise and lifestyle changes, most people will see belly-shrinking results within a couple of months (aiming for a 1- to 2-inch reduction within six months is a good, realistic goal for many). Some may see a visible difference more quickly. But again, don’t sweat what the scale says: A 2005 Duke University Medical Center study showed that exercising patients lost measurable amounts of visceral fat (as measured by CT scans) even when they didn’t lose much weight.

Front and Center

To some, it might seem silly to get so up-in-arms about a potbelly. After all, from Santa Claus to a pleasingly plump grandma, abdominal girth has traditionally been perceived as relatively harmless and imbued with emotional warmth and security.

Comforting cultural myths aside, however, the truth is that abdominal fat has serious health implications that we ignore at our own peril. This is a health and fitness problem that definitely deserves our undivided attention.

While there is no quick-fix approach to losing abdominal fat, thinking holistically and making real lifestyle changes can go a long way toward shedding that stubborn belly.

The payoff? We’ll not only look great – we’ll feel great, too.

Paunch Be Gone!

While there is no one-size-fits-all way to lose that stubborn belly, there are plenty of whole-body approaches you can use to tackle your abdominal area:

- Invest in inches. Instead of worrying about what you weigh, says health expert and author Marie Savard, MD, toss the scale and simply focus on what your tape measure says. Shaving just a couple inches of visceral fat from your waistline can drastically reduce your chances of developing heart disease, diabetes and many types of cancer.

- Manage your stress level. Everyone lives with what nutritional expert Pamela Peeke, MD, MPH, calls “annoying but livable” stress. But chronic stress that results from caregiving, marriage woes or job problems can actually pack on pounds in our midsections. Find time for yourself, create a support system, practice meditation and relaxation techniques, and learn to laugh – which not only reduces stress hormones but actually boosts your immune system.

- Eat more frequently in smaller quantities. Instead of consuming three huge meals, boost your metabolism by eating several well-balanced, smaller meals throughout the day. Work in fruits and veggies in place of sweets and refined carbs.

- Rely on fat-burning fats. Don’t fall into the trap of thinking that dietary fat is bad for you. Simply concentrate on eating healthy fats, like the essential fatty acids found in fish, nuts, seeds and avocados, as well as in olive, seed and nut oils.

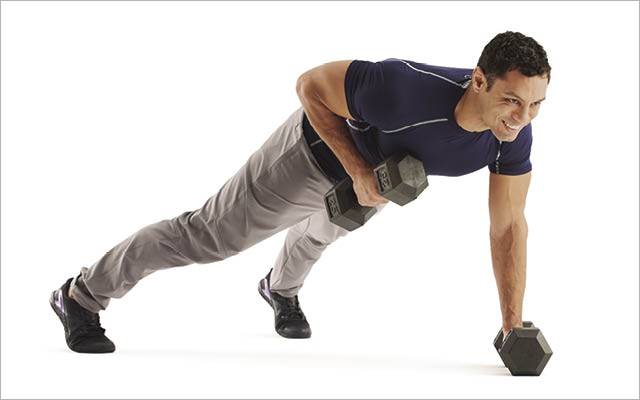

- Move your body. Try Nordic or power walking, yoga, biking, or a group-fitness class – whatever gets you going at moderate intensity for at least 30 minutes, most days of the week.

Where Belly Meets Back

In addition to increasing your risk of developing all sorts of serious diseases and illnesses, potbellies are also just plain bad for your posture and spinal alignment, says Alexandria, Va.–based chiropractor Eric Berg, DC. Berg found the abdominal-fat problem so ubiquitous that he now devotes most of his practice to helping people lose the weight instead of just opting for a band-aid approach, where patients come in over and over again for chiropractic adjustments.

“A pendulous abdomen pulls the entire body forward, so the body actually compensates sometimes by developing a hump on your upper back to help stabilize itself,” Berg says. “When you have slouched shoulders and your lower back is curved in too much, you are really distorting your posture.”

People with protruding bellies who can’t stand up straight walk into his office every day, Berg says. “Their belly fat keeps tension on the spine and creates areas of wear and tear, which might cause the spine to form abnormal wedges, so that even if you lose weight, your spine might not fit your mold anymore,” he says. “Additionally, lots of these people have knee pain because of nerves that are being pinched in their backs due to bad posture.”

This article has been updated. It originally appeared in the November 2006 issue of Experience Life magazine.

This Post Has One Comment

[…] The fat in our midsection is made up of both subcutaneous fat and visceral fat. […]