I was answering call-in questions on a radio show the other day, and in came a whopper. “What’s the one food you won’t eat?” The answer was on the tip of my tongue, but I stalled for a minute as I did a rapid calculation of whether I really wanted to say what I really wanted to say.

Why not just spill the beans? Because I never want to sound like the food police, the food snob, the finger-wagging superior judge.

I also hate it when food advice cleaves on class lines. A lot of the time, the best food can be gotten by more effort, not more money. Examples: A little oil and vinegar is usually a far better salad dressing than the priciest jar of premade dressing you can find. Making your own morning eggs is less expensive, better tasting, and better for you than a breakfast sandwich from the drive-through. And tap water trumps soda every time. Truly.

The thing I’m most scared of in the supermarket is a cheap item that people buy because they’re trying to save money. And how can I be a jerk about people trying to save money?

Could I really say I am legitimately terrified of that all-American treat, the inexpensive hamburger? Because I cower at the thought of the cheapest beef in grocery stores, and you should, too.

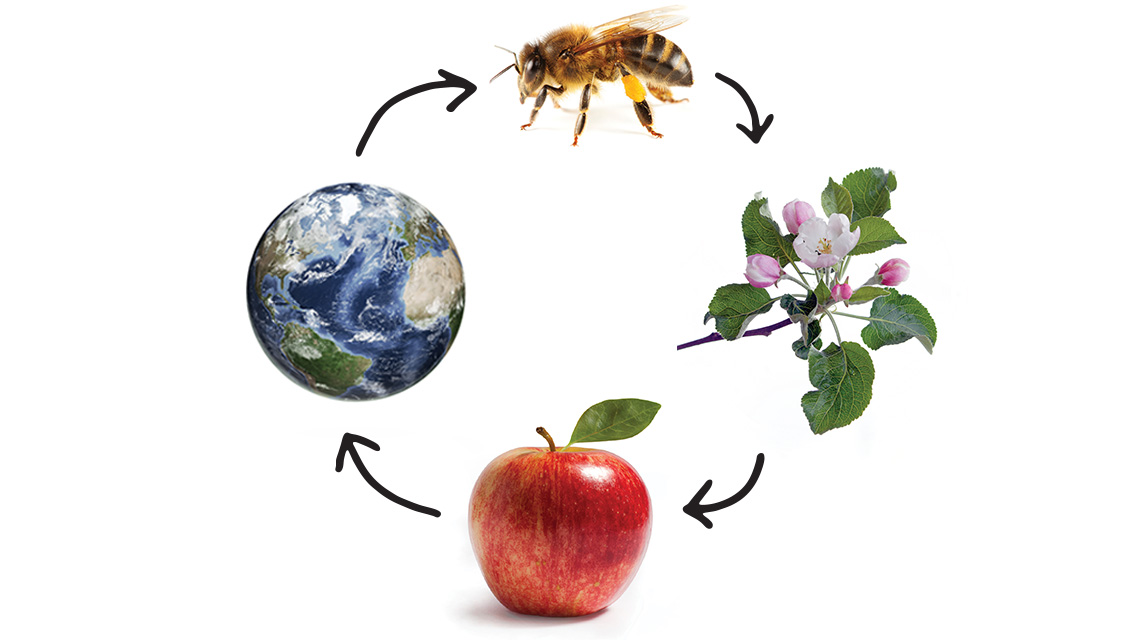

Here’s what I’m talking about: Cattle evolved to eat grass and green plants. In fact, many people think of them as giant grass-fermentation chambers, with their four stomach compartments that work together to convert something people can’t eat — cellulose — into something we can, namely milk and meat.

In the early 1970s, when the United States and Soviet Union were locked in the Cold War, the Communists were having a tough time feeding themselves. President Richard Nixon and his agriculture secretary, Earl Butz, devised a strategy to bring down the Soviets by making them dependent on us for grain. Butz encouraged U.S. farmers to plant “fencerow to fencerow,” and guaranteed that the government would pay a target price for corn, no matter how much the market price fell. So, if the target price was $3 per bushel, it didn’t matter whether corn was actually selling for $1; the farmer would get $1 from the open market and $2 from the government.

Who cares? Burger lovers!

When corn got cheaper than it had ever been in human history, people started feeding it to cows. But cows can’t really digest it. It makes them sick. So they have to be fed antibiotics, too. And then they develop E. coli, and soon, antibiotic-resistant E. coli.

The bacteria live in the gastrointestinal tracts of cattle, and if you’re packing beef in new super-modern, superfast packaging plants, there’s no time to ensure that the animal’s inside doesn’t get onto its outside.

A couple of cases in point: Did you hear about the recall of 2.5 million pounds of beef from XL Foods in 2012? The beef was in Sam’s Club, Walmart, Kroger, and Safeway stores, among others.

In 2009 the New York Times’s Michael Moss wrote about a particular burger that crippled a Minnesota woman with E. coli poisoning; it came from Sam’s Club and was made by Cargill in Wisconsin from trimmings and meat from Texas, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Uruguay. In the years since Moss won a well-deserved Pulitzer for his reporting on that single hamburger, antibiotic-resistant E. coli is still on the rise. That’s because we keep feeding antibiotics to cattle, pigs, and chickens to help them get to market weight faster and so we can keep them in dangerously overcrowded conditions.

Last fall, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a report warning that more than 2 million cases of disease in the United States are now antibiotic resistant. “If we are not careful, we will soon be in a postantibiotic era,” prophesied CDC director Tom Frieden, MD, MPH.

And in December 2013, a group of researchers at the George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services identified a strain of E. coli, H30-Rx, that is now antibiotic resistant and can spread from people’s urinary tract into the blood to cause sepsis, the most lethal form of infection. The researchers guessed this new E. coli was already killing tens of thousands of Americans each year.

I am the daughter of an economist and generally prefer to let the market dictate the products. But I don’t feel like people even know what they’re letting themselves in for when they buy these boxes of cheapo beef. There’s no black-label warning on the outside that says, “Whoa, do you know what you’re really getting here?” And expecting the average consumer to follow the beef recall of the day or the antibiotic-resistant bacteria of the week — that’s just not fair.

I feel like there’s a sort of halo of cool and efficient and classy that the big-box stores bestow on their products. The store is brand new, the cars in the parking lot are shiny, the packaging of the box of burgers looks sharp, and we are people who are virtuously pursuing bargains, saving our pennies to turn them into dimes.

And then, as if things couldn’t get worse, there’s this bit of worse: In a few sentences, it’s really hard to explain Nixon, the Cold War, the evolution and threat of antibiotic-resistant diseases, and what this all has to do with the price of hamburgers.

But, live on that radio call-in show, I took a deep breath, and I tried. I felt like a tongue-tied condescending jerk, but I really tried.

On the way out of the station, three people were waiting for me in the lobby, each wanting to ask me about their beef. Could they trust it?

I had to tell them I couldn’t vouch for any particular beef. But I told them my solution: I got to know a rancher. Namely Todd Churchill, who runs the Thousand Hills Cattle Company; he markets the beef of some 100 ranchers who raise cattle on grass without antibiotics. Supermarket beef to me now has a weird ammonia and plastic aftertaste. I love the taste of this Thousand Hills meat, though: It’s deep and winey and beefy.

Many states have directories to help connect consumers directly with farmers and ranchers. The website EatWild.com provides a national directory of those raising grassfed beef, a source you should check out if you want to try my strategy of minimizing risk and maximizing pleasure by actually finding real people who grow your food.

That said, please know I don’t buy grassfed beef because I have the illusion I’ll never get sick; I could still get listeria from alfalfa sprouts or many other sources. After all, life is a state of risk. I feel better knowing I’m not blithely taking on a dumb and dangerous amount of risk, however. And I almost feel OK telling people why they might not want to either.

This Post Has 0 Comments