Darrold Glanville loves bread. Eight years ago, he retired as a partner in a biotech company and started experi-menting with baking, inspired by his favorite crusty European loaves. He got so good at it that he joined forces with a local baker to sell his wares.

Soon he wasn’t feeling well.

Glanville suffered from sinus problems and severe acid reflux. He went to doctors, including an allergist and gastroenterologist, even to the renowned Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. No one could detect what was going on in his body.

Then, after eating a big pasta dinner and getting sick the next morning, Glanville had a eureka moment. “His enlightenment came at an Italian restaurant,” remembers his wife, Marty: Perhaps his troubles were caused by gluten.

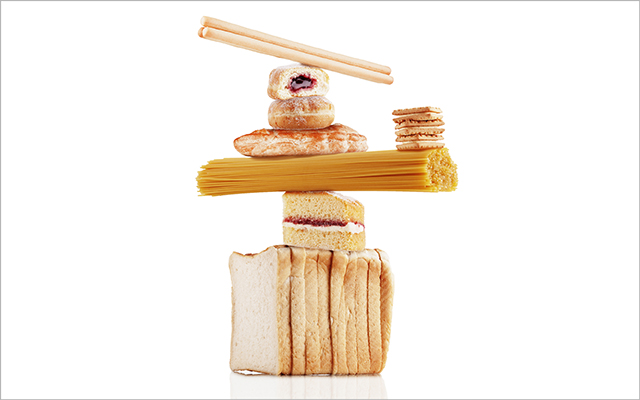

Gluten is a storage protein found in wheat and other grains, like barley, rye, spelt, and triticale. It makes dough stretchy and pasta pliable. It helps trap air while baking to make bread light and cakes spongy. But gluten can be difficult for some people to digest.

Gluten is not only problematic for those with celiac disease, an autoimmune disorder that affects nearly 1 percent of Americans. Those without celiac disease can also have gluten sensitivity, which can incite inflammation and attendant problems throughout the body. In fact, a 2002 New England Journal of Medicine article connected gluten to 55 conditions, including anemia, depression, cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, fatigue, and irritable bowel syndrome.

Glanville resisted the idea of going gluten-free. When he didn’t eat gluten, however, he had to admit that he was feeling better. So, determined not to give up on his beloved bread, he started researching various wheat varieties. What he and Marty discovered is that they really didn’t know much about the flour they had been eating all their lives.

They also found various theories on why there seems to be more gluten (and gluten intolerance) in modern society.

“The grains we eat today bear little resemblance to the grains that entered our diet about 10,000 years ago,” argues neurologist David Perlmutter, MD, author of the new book Grain Brain: The Surprising Truth About Wheat, Carbs, and Sugar — Your Brain’s Silent Killers (Little Brown, 2013). “Modern food manufacturing, including aggressive hybridization, have allowed us to grow grains that contain up to 40 times the gluten of grains cultivated just a few decades ago.”

On the other hand, a 2013 study funded by the USDA and published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry by wheat expert Donald D. Kasarda, PhD, shows gluten levels in various varieties of wheat have changed little since the 1920s. The difference is how much gluten Americans eat. In 2000, people consumed nearly 25 percent more gluten than in 1970. We’re also eating three times as much vital-wheat gluten, a food additive made from wheat flour that’s added to food products to improve texture.

Researchers not only disagree about how much wheat has changed, but also about how susceptible we are to gluten. Some estimate that one in 20 Americans is sensitive to it; others, including Perlmutter, think that as many as 40 percent of Americans can’t process gluten.

Glanville is one of these folks who can’t digest the substance from modern wheat. But when he switched to eating only ancient varieties, commonly referred to as “heritage grains,” the symptoms he suffered while eating modern wheat disappeared.

Inspired by Darrold’s experience, the Glanvilles decided to mill and sell heritage wheat. In 2009, they started Sunrise Flour Mill in North Branch, Minn., and became part of the larger heritage-grain movement growing across the nation.

Saving Wheat

Some of the heritage varieties Glanville tried baking with include full and complex einkorn, sweet and nutty emmer, and deeply nutty spelt. While he appreciated the full flavors of these wheats, they did not have the baking qualities he was looking for: a good rising and lighter-quality crumb. The bread with the taste and texture he likes best is made from Turkey Red wheat, which was originally brought to the United States in the late 1800s from the Ukraine.

Marty says that food baked from Turkey Red flour has a rich, nutty flavor. It’s truly tasty, customers have told her.

Heritage wheats don’t always behave in the kitchen the same way conventional flours do. “Heritage wheat is not a monoculture, so it can have variations at times in baking properties,” Glanville says.

Like wild plants that grow in their particular niches, heritage grains thrive in some places and not others. Far from eastern Europe, Turkey Red also grows well in the soil and climate of western Kansas. Darrold and Marty purchase this wheat from Mennonite farmers who raise it there, making the 2,000-mile round-trip drive themselves to pick up the valuable grain.

The Glanvilles are currently experimenting with more heritage varieties. They’re also looking for organic heritage-wheat farmers closer to home — and given the emerging popularity of these heritage varieties, it’s likely they’ll make a connection soon.

Evidence of a growing movement can be found at the Heritage Grain Conservancy, an organization founded 20 years ago by Eli Rogosa, which preserves almost-extinct heritage grains — and it can barely keep up with demand. “We’re really overwhelmed with interest,” Rogosa says.

Part of that interest is coming from farmers, part from the increasing number of people across the country who are seeking gluten-safe grains and growing food themselves to ensure that it’s healthy.

The names of the seeds Rogosa sells have an exotic air — Black Winter emmer, Banatka, Rouge de Bordeaux, Zyta, and Bezbanatskaja. But, she says, “they’re easy to grow. Anybody can do this. It’s a grass.”

Rogosa, who manages her biodiversity conservation farm in Colrain, Mass., has been collecting and growing heritage wheat since the early 1990s. She worked for 15 years with Israeli and Palestinian gene banks to collect near-extinct ancient wheats before they were lost to the world, then was funded by the European Union as a research partner to collect nearly lost, rare wheats in Europe.

Heritage wheats are like heirloom vegetables. An heirloom is an old cultivar maintained by gardeners and farmers and not used in modern large-scale agriculture. Heritage wheats are “landraces,” varieties that have developed and adapted to local environments.

As director of a USDA-funded project based at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Rogosa planted and evaluated hundreds of heritage wheats over five years. Many boasted higher yields in organic soils and were more disease resistant than commercially available varieties. “Landrace wheats have extensive root systems,” says Rogosa. “They’ve evolved to survive and to search out nutrients. They’re taller to compete with and suppress weeds. They [also] have a richer flavor and lower gluten.”

Today, Rogosa runs a bakery dedicated exclusively to einkorn, which was domesticated in Mesopotamia 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. While other heritage varieties she’s grown have richer flavor and are more easily digestible than modern wheat, they’re not as high in nutrients as einkorn. “Einkorn has a very rich flavor. It’s twice as high in protein and minerals as modern wheat,” she says, “and it’s safer for people with gluten allergies.”

Like Darrold Glanville, Rogosa has personally benefitted from making the switch from conventional wheat to heritage: “Modern wheat is bred for bubbles, for gluten elasticity. That’s not nutrition. It’s glue. When I eat einkorn, I feel better, not bloated. I have more energy.”

This Is Your Body on Gluten

Glanville says he, too, uncharacteristically lacked get-up-and-go before he stopped eating modern wheat. “I was a couch potato with no energy,” he says. “I think I was malnourished.”

Malnourishment is a key symptom of celiac disease and other gluten-related disorders, because gluten-intolerant folks suffer a massive disruption in their digestive process when they eat gluten. Normally, as food is broken down in the gut, digested nutrients pass through the intestinal lining to the bloodstream. In some people, however, the proteins in gluten that can be toxic — primarily gliadins and glutenins — prompt the body to release zonulin, a substance that works like a crowbar, prying apart the intestinal lining and allowing undigested food into the bloodstream. As a result, the body doesn’t absorb the nutrients it needs. And the immune system attacks the undigested food as if it were a bacterium or virus, which causes inflammation throughout the body, setting the stage for any number of chronic diseases.

Celiac disease is four times more common in the United States today than it was in the 1950s, motivating researchers to examine why gluten sensitivities are on the rise. Donald Kasarda’s study points toward increased wheat and vital-gluten consumption as possible culprits.

Another theory is that selective breeding and hybridizing, which started in the 1950s, may have changed the structure of wheat. A 2010 study performed by molecular biologist Hetty van den Broeck, PhD, and funded by the Celiac Disease Consortium in the Netherlands, examined the celiac-disease toxicity of modern and heritage wheats by contrasting how many disease-stimulating epitopes they contain. (An epitope is part of an antigen that provokes the immune system to produce antibodies and leads to the destruction of the tiny intestinal villi that help absorb nutrients.)

The study showed that some heritage wheat contains a lower amount of celiac-related epitopes compared with modern wheat. It’s an exciting finding, van den Broeck says, because “large-scale consumption of low-celiac-disease-toxic varieties would considerably aid in decreasing the prevalence of celiac disease.”

The Future of Ancient Grains

This finding begs the question: Should we all be switching to eating heritage grains?

“Ancient wheats do have fewer toxic epitopes,” says Peter Green, MD, professor of clinical medicine and director of the Celiac Disease Center at Columbia University. But, he says, some of the patients he sees with gastrointestinal issues they’ve attributed to gluten turn out to have something else, like bacterial overgrowth or fructose intolerance. “Not everyone is gluten sensitive,” says Green. “The whole population doesn’t have to be on a gluten-free diet.”

Alessio Fasano, MD, who heads the Center for Celiac Research and Treatment at MassGeneral Hospital for Children in Boston, agrees that only genetically predisposed people have to worry about celiac disease and gluten consumption. Celiacs should not consume heritage wheat, he says, because they cannot eat any gluten whatsoever. “However, some people with non-celiac gluten sensitivity might have a tolerance to ancient grains that have a lower gluten content because the grains have less of a toxic load,” Fasano says.

What’s clear is that more research is needed to understand the relationship between gluten, grains, and our guts. Green says there is still a lot we don’t know about gluten; research into gluten sensitivity is today where celiac research was 30 years ago. (To learn more about gluten, see “Gluten: The Whole Story“.)

The Glanvilles are just happy that they got to the bottom of their own health mysteries. When Marty saw Darrold’s symptoms disappear after making the switch to heritage grains, she followed him. Nearly all the joint pain she’d suffered for years disappeared, making her think she is gluten sensitive, too.

For Marty, the experience of learning about modern-wheat flour and its effects on her body deepened one of her convictions: “It’s so important to know what we’re eating,” she says.

Darrold Glanville not only feels great after switching to heritage wheat, he now enjoys his Turkey Red bread even more because he loves its heartier taste. “Even if we weren’t gluten intolerant tomorrow,” he says, “we would still use this flour.”

Get Your Grains On

People are aware of the benefits of buying local fruits, vegetables, dairy, and meats, but few have yet to start buying locally grown heritage grains. Your best bet is to ask for them at your local co-op or farmers’ market. Here are a few sources to get you started.

Anson Mills: Columbia, South Carolina

Farms and mills heritage-wheat varieties, including Red May, Red Fife, French Mediterranean, and Sonora.

Sunrise Flour Mill: North Branch, Minnesota

Darrold and Marty Glanville’s company sells a variety of products, including Turkey Red heritage-wheat flour.

Hayden Flour Mills: Phoenix, Arizona

Part of a collaboration of farmers and organizations that recently received a grant from the Western SARE (Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education) program to revive the production, milling, distribution, and marketing of White Sonora soft-bread wheat and Chapalote flint corn, the oldest existing grain varieties adapted to the arid Southwest.

Heritage Grain Conservancy: Colrain, Massachusetts

Eli Rogosa’s outfit sells a variety of landrace seeds, as well as einkorn grains, flour, and pasta.

Perfect Artisan Heritage-Wheat Recipe

Recipe courtesy of Marty and Darrold Glanville, of Sunrise Flour Mill (www.sunriseflourmill.com)

Ingredients:

- 1 tsp. sea salt, plus 1 tbs. for later

- 1 tsp. dry active yeast

- 2 lbs. Turkey Red Refined flour, divided

- 2 3/4 cups water, divided

Instructions:

- Mix 1 tsp. salt and yeast into 1 pound of the flour with a whisk. Add 1½ cups water, and mix until a sticky wet dough has formed. Refrigerate overnight.

- The next day, remove from the refrigerator and allow to warm for about an hour. Then, add the remaining 1 pound of flour, 1 tablespoon of salt, and 1¼ cups of water. Mix and knead by hand until the dough is wet and thoroughly combined.

- Let it proof about two hours in a covered container.

- Now comes the critical part: The dough needs to stay as wet as possible. (The wet dough is the secret to baking light artisan bread with large holes in the crumb.) Sprinkle some flour on the outside so the dough can be worked, but add as little flour as possible to the inside of this dough ball. Lift the ball a bit with a dough tool, and sprinkle some flour under the ball.

- Now, think of the ball as a clock. Grab a quarter of the dough at 3 o’clock and stretch it upward as far as it will go without tearing, hopefully 8 to 12 inches. Lift and push this stretched dough to the middle of the ball. Repeat at the 6, 9, and 12 o’clock sides of the ball.

- Return to the covered bowl and proof for one hour. Preheat oven to 475 degrees F.

- Repeat stretching the dough from the 3, 6, 9, and 12 o’clock sides to the middle. After 30 minutes or less, the ball will have come back together again. The dough can now be divided and formed into the desired shape, for example, focaccia, baguette, bread sticks, etc. Take care to divide and shape so that the air bubbles that have been created in the dough while proofing are not pressed out.

- A pizza stone placed in the oven during preheating provides a more intense heat. Small loaves can be baked on a pizza stone covered with the top of a La Cloche clay baker. If there is nothing to cover the bread with, a metal pie pan and a few ice cubes can be used to add humidity to the oven.

- Every oven is different, but in general small round loaves and baguettes take about 12 to 14 minutes; larger loaves like ciabatta take 17 to 20 minutes. A thermometer inserted into the thickest part of the loaf should read 200 to 210 degrees F.

- This flour creates a rather light-colored crust even at this temperature. You can try brushing with olive oil or an egg wash before you bake to make it browner.

Alternate Baking Method: The ideal method of baking actually utilizes a cast-iron Dutch oven, 8 or 9 inches across the bottom. Preheat oven and Dutch oven to 475 degrees F at least 30 minutes prior to baking; 45 minutes is even better. Place half the dough in the ungreased Dutch oven, cover, and bake 30 minutes. Remove lid and bake another 10 to 15 minutes more depending on how brown a crust you want. The internal temperature of the bread, as with other methods, needs to be at least 200 degrees F.

This Post Has One Comment

Hi, can you comment on the differences between heritage grains and ancient grains? Specifically, I’d love to hear about any differences in gut health aspects and baking characteristics.