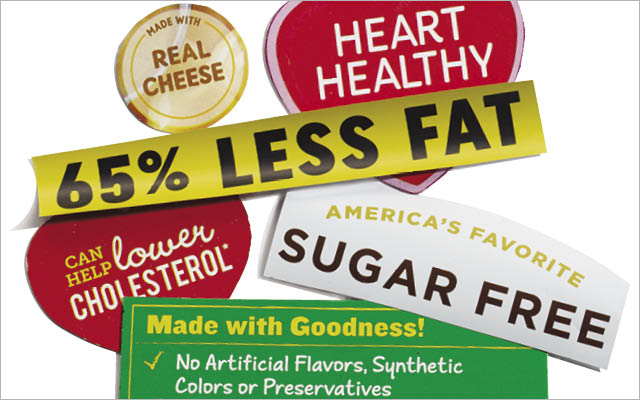

Read food labels, but don’t necessarily take them at their word. Food makers often use fuzzy language as sneaky sales strategies. Here’s a peek behind the mixed messages on too many food packages.

Clever Names: Just as cars are named to suggest speed or luxury, food products are often christened — after feedback from market research and consumer focus groups — to sound tasty and healthy. Unlike the “organic” designation, terms like “farm,” “whole,” and “simply” in brand names or labeling are not regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Even the term “healthy” is a sales pitch without oversight: Soda, potato chips, and ice cream have all been advertised as good for you at one time or another.

Misdirection: Magicians trick you by diverting your attention; food makers do the same with labeling and advertising. To obscure the fact that they’re loaded with sodium, macaroni-and-cheese packages promise that their contents have no artificial dyes, flavors, or preservatives. Breakfast-cereal boxes shout that their contents are fortified with vitamins and minerals so you overlook the sugar content. The list of possible misdirection cues is endless.

Healthwashing: Many junk foods, including sodas, chips, and prepared meals, now come in organic versions. They may be marginally healthier for you, but they’re still junk food. And claiming a food is “mom approved” may be the ultimate in healthwashing; there is no official FDA “mom” to sanctify it.

Greenwashing: Terms like “simple,” “farm raised,” “responsibly made,” “sustainable,” and “all natural” are pure feel-good catch phrases implying that the foods are good for you and the earth. Images of sunrises, countrysides, or woodgrain on packaging bolster this in our minds. And we even perceive food as healthier when the same calorie count is printed on a green label rather than a red one, according to a Cornell University study. The FDA doesn’t regulate such greenwashing: As New York University public-health professor Marion Nestle, PhD, MPH, writes in What to Eat, “‘Natural’ is on the honor system.”

Medical Claims: The FDA closely regulates direct medical claims, but there are many creative ways to skirt this. For instance, a manufacturer can’t claim a product will “boost the immune system” but it can say it will “support” it — a subtle distinction when you’re sick and looking for quick relief.

Sugary Deceptions: Nature — and food scientists — created myriad types of sugar. Ingredients are listed on packages in descending order of quantity, and one trick is to flavor foods with multiple sweeteners so “sugar” doesn’t appear high on the list. If a product claims to contain “no high-fructose corn syrup,” it could still be chock-full of other sugars, including regular corn syrup, honey, maple syrup, fruit juices, and so on. “Sugar-free” doesn’t mean a product isn’t sweet or has fewer calories than the regular version; it may have more. And it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s good for you. The FDA requires “sugar-free” products to contain less than 0.5 grams of sugars per serving, but they may still contain carbohydrates from other sources. “Low-calorie” products like sodas and desserts may include sugar alcohols (such as sorbitol, mannitol, xylitol, or isomalt) that can still send you on a blood-sugar roller coaster, or artificial sweeteners (such as aspartame, saccharin, or sucralose) that can have a “rebound” effect, inspiring you to eat more under the misperception that they’re healthy.

(Many sugary cereals and sweetened yogurts will no longer be able to market their foods as “healthy” under new, proposed rules. See “FDA Proposes Updates to “Healthy” Food Criteria” for more.)

Food-Label Glossary

Natural Goodness

“Farm-Raised”: The U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) does not define a “farm,” so this is a feel-good phrase imparting a sense of “all natural.”

“All Natural”: Sounds ideal, but this all-too-common greenwashing phrase means nothing at all. The FDA doesn’t currently define or regulate its use (although there are promises from the agency that it will soon), so many foods — even those with artificial dyes, chemical preservatives, and GMOs — may be labeled “100% natural.” Images on packaging of sunrises, the countryside, or wood grain bolster this. As New York University public-health professor Marion Nestle, PhD, MPH, writes in What to Eat, “‘Natural’ is on the honor system.”

“Fresh”: Means many things — including cooked or frozen. The FDA requires that “fresh” foods be raw, never heated or frozen, and contain no preservatives, but they can still receive post-harvest pesticides; be washed in mild chlorine or acids; receive ionizing radiation; and be protected in approved waxes or coatings. Fresh dairy products can be pasteurized. And food may be labeled “fresh frozen” or “frozen fresh” if it was freshly harvested when frozen — and it could have been blanched as well.

“Organic”: Like the term “natural,” “organic” was once open to interpretation, but since 2002 the strict U.S. National Organic Program certification process has been governed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. To win a USDA Organic label, a minimum of 95 percent of the ingredients must have been grown or processed without synthetic fertilizers or pesticides, among other standards. The “made with organic ingredients” label means that a minimum of 70 percent of ingredients meets the standard. Note, though, that many so-called organic foods are imported from highly polluted countries such as China and can contain high levels of heavy metals and other toxins. And “organic” doesn’t necessarily mean healthy: Organic cookies, chips, soda, and other food can still be loaded with sugar, unhealthy fats, and more.

“Non-GMO”: Labeling whether food is bioengineered (BE), or derived from genetically modified organisms (GMO), is currently voluntary under the FDA. In December 2018 the USDA passed its National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard, which will require BE and GMO labels as of January 1, 2022. In the new act, the USDA defines bioengineered food “(A) that contains genetic material that has been modified through in vitro recombinant deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) techniques; and (B) for which the modification could not otherwise be obtained through conventional breeding or found in nature.” Critics, however, complain that this definition is already behind the times: A new generation of GMO 2.0 “synbio” (for synthetic biology) foods is being created by editing genes or even introducing completely new DNA sequences using the computer software CRISPR. (For more on synbio foods, see ELmag.com/gmo-2-0.) And also remember that “non-GMO” does not mean a product is organic.

“Biodynamic”: Austrian philosopher, social reformer, and Waldorf-education architect Rudolf Steiner, PhD, outlined the tenets of biodynamic agriculture in 1924, establishing the first rules for an organic farming system. Starting in 1928, the Steiner-inspired Demeter International has certified biodynamic farms and products, including wines. These items must meet U.S. National Organic Program base requirements plus even stricter rules for fostering biodiversity, sustainability, water conservation, and disease, pest, and weed control.

“Fair Trade Certified”: The global Fair Trade movement is designed to ensure that producers get fair wages and payment for products, to support environmental stewardship, and to help consumers make conscious choices to support these producers.

Sugary Sweet

“No Added Sugar”: A product might not have added sugar, but it can still be loaded with natural sources of sugar including fruit juice; sweeteners such as maltodextrin; or other carbohydrates that our bodies turn into sugar. “Unsweetened” is also commonly used: This doesn’t mean a product isn’t sweet; it may have lots of natural sugars, but no added ones.

“Lightly Sweetened”: The FDA regulates this label, but only on canned berries — and amounts vary by berry type. Beyond that, the term is wide open to an advertiser’s discretion, so it doesn’t necessarily mean a product won’t give you a sugar rush. But how much is too much? In August 2018, a judge certified that “lightly sweetened” was false advertising when used to promote Kellogg’s breakfast cereals that contained up to 40 percent added sugar.

“Sugar Free”: This doesn’t mean a product isn’t sweet or has fewer calories than the regular version; it may have more. And it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s good for you. The FDA requires “sugar-free” products to contain less than 0.5 grams of sugars per serving, but they may still contain carbohydrates (and calories) from other sources. Often “low-calorie” products like sodas and cookies include artificial sweeteners (like aspartame, saccharin, or sucralose) and sugar alcohols (such as sorbitol mannitol, xylitol, or isomalt), all of which are lower in calories but can still send you on a blood-sugar roller coaster.

“Made With Real Fruit”: Many products indeed contain fruit — often as sweeteners. And they might not include the type of fruit shown on packaging. Cheap grape and pear juices can impart a generic “fruity” flavor that can masquerade as most any other fruit.

Healthy Promises

“Low Sodium”: This FDA-regulated term certifies that each serving contains no more than 140 mg of sodium. “Reduced sodium” must have at least 25 percent less sodium than the regular version of the product — but that doesn’t guarantee it’s not still packed with salt. And beware: Foods labeled “salt free,” “no sodium,” or “sodium free” can still have 5 mg of sodium.

“Fat Free”: The FDA’s requirements for nutrient-content claims almost require a legal team to decipher — and one with a lot of time on their hands. Without regard for the quality or healthiness of the fat, “fat free” or “zero fat” doesn’t mean that a product actually has zero fat, just that it has a small amount: 500 mg per serving. “Low fat,” meanwhile, means it has no more than 3 grams per serving.

And there are numerous loopholes available. “Reduced fat” or “lower fat” means the product must have at least 25 percent less fat than its regular version — but that doesn’t guarantee it’s not still packed with unhealthy fat. Similar regulations govern advertising saturated-fat, cholesterol, and calorie content with similar levels. Labels like “lean” and “extra lean” also have corresponding requirements. But remember: If a product is low in fat, it usually has other ingredients making up for the subsequent loss in flavor, such as sodium.

“Whole Grain”: This can mean a variety of things and requires a closer look at the ingredients label. Products that promise “100% whole grain” or “100% whole wheat” should contain exclusively whole grains and list whole-wheat flour or other whole grains as the primary ingredient — and not include other refined partial grains. Advertising claiming “made with whole grains” might mean the product contains only some whole grain, along with other processed grains.

“Superfood”: This is a supermarketing term usually bestowed on a product by growers’ councils (based on studies funded by the council) and trendy health gurus, or as a catchy phrase by the media. The FDA does not regulate the term, but the European Union banned such claims in 2007 unless there’s credible scientific proof — and, so far, most “superfoods” aren’t passing the test.

Meat and Eggs

“Free Range”: There’s no FDA definition governing the amount or quality of playtime a chicken has to root freely around a barnyard, so buyer beware — this is a marketing term, as are “pasture-raised” and “cage-free.” And while not all free-range chickens are organic, an organic chicken must be free-range, warns the National Chicken Council.

“Animal Welfare Approved”: This label certifies that animals were raised outdoors on pasture for their entire lives on an independent farm using sustainable farming techniques through to humane slaughtering and is awarded by the agricultural organization A Greener World (AGW), which also certifies organic, grassfed, and non-GMO products. The Humane Farm Animal Care group also issues “Certified Humane Raised and Handled” labels to products to certify they’ve been humanely raised “from birth through slaughter.” The Global Animal Partnership (GAP) was started by Whole Foods in 2008 to certify animal welfare, including emotional well-being, up to requiring that animals be stunned before slaughter.

“Grassfed”: There’s evidence to suggest that animals fed grass and forage — rather than grain — are healthier, which results in more-nutritious and better-tasting meat and dairy products as well as more sustainable farming and ranching practices, according to the American Grassfed Association. The FDA began certifying grassfed products in 2006. Grassfed cattle are not necessarily “free-range” or “pasture-raised,” and these terms are not regulated. “Grass-finished” cattle are fed grass or forage in the final weeks before slaughter; to quickly bulk them up, conventional cattle are often finished on corn that includes growth hormones and prophylactic antibiotics to prevent diseases that spread quickly in feedlots. Some people like the flavor of grass-finished beef; others find it too strong tasting and prefer organically raised, grassfed cattle finished on pure corn.

“No Antibiotics”: To prevent animals from contracting diseases in overcrowded feedlots, they’re given prophylactic antibiotics. But an overuse of antibiotics encourages the growth of drug-resistant superbugs that can infect people. Protecting humans from such superbugs is “a national priority,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The USDA Process Verified label guarantees that no antibiotics were used in producing certified beef and poultry meats and eggs. Sound-alike “no antibiotics” labels are not USDA approved.

“Wild-Caught”: Fish and seafood are caught in the wild using lines, nets, traps, trawls, dredges, and harpoons. Farmed marine animals — which can include GMO-modified salmon — are raised in ponds, tanks, and raceways or in oceans with pens and other types of “cultures.” There is currently no government-certified labeling for wild-caught fish, so such advertising is on the honor system. The MSC label granted by the London-based Marine Stewardship Council, the ASC label from the European Aquaculture Stewardship Council, the Global Aquaculture Alliance, and the Wild American Shrimp label certify sustainably caught or raised seafood. Fresh, frozen, and canned products may claim they are sustainably caught, but there’s no official certification oversight. The Humane Farm Animal Care group, which issues “Certified Humane Raised and Handled” labels for meat products, is working to create marine animal certification. None of these certifications currently examines working conditions, however, and there is rampant slavery in the large Thai fishing industry; you can research seafood products for slave labor at seafoodslaveryrisk.org. Some farmed fish is being advertised as “organic,” but the USDA does not yet have standards in place. To help make smart seafood choices, see the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s seafoodwatch.org.

“Dolphin Safe”: Following a public boycott in the late 1980s, the U.S. government created dolphin-safe standards for tuna fishing that is followed by most U.S. fisheries and backed up by can labeling. Tuna-fishing methods can still have by-catch, and “dolphin safe” does not mean other marine animals aren’t harmed.

This originally appeared as “How to Read Food Labels” in the May 2019 print issue of Experience Life.

This Post Has One Comment

Thanks for the information..Things you think you might know, but when you read about it, you understand it better