Tristan Gooley has led expeditions around the globe; climbed peaks in Africa, Asia, and Europe; and studied the practices of remote tribal peoples. He and the late Steve Fossett are the only people known to have both flown and sailed solo across the Atlantic Ocean.

While these milestones are remarkable, his teachings on natural navigation — plotting a course using the sun, stars, weather, sea, plants, and animals — might be his greatest legacy.

For Gooley, natural navigation isn’t a survival skill, although this rare art could save you in a life-or-death situation. It’s a means to engage more meaningfully with the world.

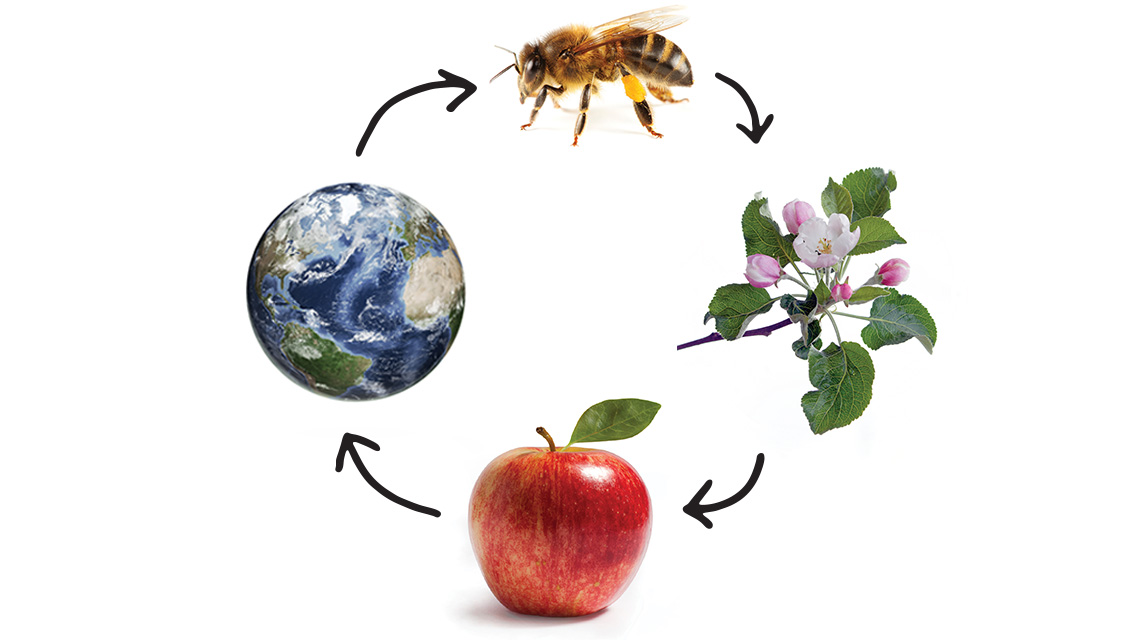

“Reading nature allows us to see the roots that sustain and explain everything around us,” the British native writes in How to Read Nature: Awaken Your Senses to the Outdoors You’ve Never Noticed.

Reading nature is an act that creates joy. “It allows each of us to see each living thing, object, and idea within its own intricate network,” he explains. “We can look at a plant as a source of food and as a key to a moment in time — at the same time.”

It’s also an act of resistance. “Most people remain oblivious to the sounds of the birds all around them,” Gooley notes. People who read nature take the extraordinary view of life outside of themselves.

Knowing what to look for when viewing your surroundings makes natural navigation a unique skill that enhances any adventure. This “deep reading of nature,” he argues, “is life-enhancing to the point that it changes who we are.” —Heidi Wachter

Gooley’s Exercises for Natural Navigation

Seeing the World Around You in a Tracker Puddle

The concept behind tracker puddles is simple: The more erosion from somebody or something traveling, the more likely there is to be a puddle in one spot. But just because it is simple does not mean that it cannot be beautiful, and the lighter the footprints, the more exciting it is to spot the puddle they create.

The next time you are walking along a country path and you find a puddle on an otherwise level stretch of mud, pause to see if you can solve the puzzle as to why it is there. Peer at the undergrowth on either side of the path and look for evidence that someone’s been busy.

Animals have their own network of paths. The badger’s big, straight ones are quite easy to spot, especially if you get down low and view them from badger level. There are many others, though, like deer and rabbits, that will forge their own highways, and where these intersect with our own paths, it follows logically that there will be more wear to the path. Only a little bit compared with the junction of vehicles or even walkers, admittedly, but that is all it takes for one small patch of ground to get worn down a tiny bit, which in turn makes it the logical place for the water to collect after the next downpour.

The next thing that happens is that these baby puddles grow, helped along by two factors. Firstly, the small hollow created by the intersection of humans and animals stays soft and wet longer after rain than the drier mud around it. This means that when the next feet land there, whether the cumbersome boots of a walker or the feathery feet of a vole, they churn the mud up a little bit more than the dry, hard ground to the side, and this erodes the land more quickly in that one small spot. A self-reinforcing cycle has begun, and the puddle grows a small amount.

Secondly, all small puddles act as minuscule reservoirs for animals in that habitat. Thirsty animals will seek out the puddles, just as they travel to ponds and lakes, and this leads to yet more footfall, encouraging the infant puddle to grow.

Finding South Quickly

Notice how the sun is due south in the middle of the day. This is true every day of the year everywhere north of the Tropic of Cancer, which includes all of Europe and the United States.

The next time you see a crescent moon high in the sky, join the horns of the moon in a straight line and extend this line down to your horizon. You will be looking roughly south.

If you don’t have a moon to guide you, look for TV satellite dishes: On the East Coast and in the Midwest of the United States, they generally point southwest, and in the West and Southwest, they tend to point southeast.

Following a Duck’s Wake

Seek out a pair of paddling ducks on a relatively calm pond.

Look at what the water is doing all around your ducks. Spend a moment getting to know the shapes and rhythms of the water, not just by the ducks, but over the area you are looking at more broadly. This is the “baseline water behavior.”

Now look at the water behind one of the ducks as it paddles. You will quickly spot the V-shaped wake, a series of ripples that have been created by this one bird and that spread out and over the water, superimposing themselves on whatever patterns were there before. Next, look at the very similar ripples behind your duck’s companion and watch those march out across and over the water behind them as they both swim.

Examine the place where these two patterns touch and then overlap. Study this for a few seconds. Can you see how a totally new pattern is created, one that is formed by the combination of the sets of ripples generated by each duck, but which looks different from each one individually? You should be able to see a new criss-cross pattern.

The water’s behavior where the two sets of waves overlap is unique, which is why the Pacific Island navigators were able to work out where they were when two sets of swells ran into each other near islands.

When waves run over each other like this and create a new pattern, scientists call it “wave interference.” Where two crests coincide, the water becomes double the height it was before; where two troughs coincide, a doubly deep trough is created. But where a crest from one set of ripples or waves meets the trough from another, they cancel each other out.

Every Tree Has a Story

Spend 10 minutes sketching a tree.

Now write a short story about the experience of looking at a tree in this way. If you find conflict in your scene, brilliant, use it. If not, search for it. It can be the sight of past violence: trauma done to the tree by animals or insects, lightning, snapping, or the decay and death of a branch. Or it can be an inner conflict: Perhaps the effort required to complete this exercise makes you angry or reminds you of an English teacher you disliked. If you still have no luck, invent it. You never know, you might enjoy it.

Excerpts from How to Read Water and How to Read Nature, by Tristan Gooley, copyright © 2016 and 2017 by Tristan Gooley. Reprinted with the permission of The Experiment, LLC. Available in the U.S. and Canada. theexperimentpublishing.com

This Post Has 0 Comments