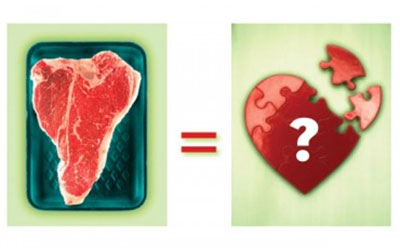

If the nation’s health police had a 10-Most-Wanted poster, cholesterol’s mug shot would be front and center. It stands accused of aiding and abetting the country’s No. 1 killer: heart disease. But cholesterol may have been implicated unfairly, framed for crimes in which it acted more as an innocent bystander — or even as a well-intended Good Samaritan who got caught up in the crossfire.

The case against cholesterol traces back to the mid-20th century, when scientists first found its sticky fingerprints inside plaque-filled arteries. The leap from having located blood-borne cholesterol in arterial plaques to assuming it came from the cholesterol in food (and was a root cause of arterial damage) was a short and notoriously unscientific one. (You can read more about the scientific controversy surrounding cholesterol in “Cholesterol Myths,”.)

Nevertheless, the medical and dietary-advice establishments put out a loud all-points bulletin: If you eat fat-rich, cholesterol-rich foods, like beef, butter and egg yolks, you’re digging your own grave — one forkful at a time.

That was the line adopted by the American Heart Association, American Medical Association and the Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (primary sources for most mainstream health journalists). And so that was the story that got told by the media — for decades on end. Eventually, it became a sort of sacrosanct “common knowledge.”

Yet, not everyone has been convinced. A number of skeptical health professionals — including a variety of doctors and academic researchers — have long insisted that the establishment doctrine on cholesterol is misguided, has been manipulated by pharmaceutical interests, and that the so-called scientific conclusions supporting the now-accepted-as-fact hypotheses are, in fact, deeply flawed.

Some of these skeptics have written copiously footnoted books — like The Cholesterol Myths by Uffe Ravnskov, MD, PhD; The Cholesterol Hoax by Sherry Rogers, MD; and Know Your Fats by biochemist Mary Enig, PhD — demonstrating that the scientific evidence tying saturated fat and cholesterol to heart disease has never been particularly convincing, and that the evidence tying intake of dietary cholesterol to high levels of cholesterol in the blood is circumstantial at best.

The advice we’ve been given (to cut out all foods high in saturated fat and cholesterol and embrace diet foods instead) has actually made our heart-disease problems far worse, these experts say. It has distracted us from understanding cholesterol’s health-supporting roles in the body, robbed us of our pleasure in eating, given rise to obesity and resulted in widespread overmedication. It has also dissuaded us from taking more effective and sustainable steps — like embracing a high-nutrition, anti-inflammatory diet and exercising more — that would have improved national health and dramatically lowered healthcare costs.

For the most part, these cholesterol iconoclasts have either been ignored or dismissed as heretics by mainstream medical organizations. But over the past several years, as the role of inflammation in disease has become better understood, a growing number of well-recognized experts have begun agreeing that much of what we’ve been told or assumed was true about cholesterol is just plain wrong.

In particular, now that the important health-supporting role played by natural dietary fats has become better understood, the characterization of dietary cholesterol as a big health-risk factor has been called into serious doubt.

Robert Knopp, MD, an endocrinologist and the endowed professor of lipid research at the University of Washington in Seattle, puts it bluntly: “Cholesterol in the diet is a minor player in heart disease.”

A significant body of scientific evidence (much of which is referenced in Ravnskov’s and Rogers’s books) points to high cholesterol as a marker of inflammation-based diseases like heart disease, rather than a root cause. Meanwhile, science is also revealing that trans fats, sugars, refined carbohydrates — particularly when combined with a too-low intake of plant-based, whole-food nutrition — are the primary culprits in creating inflammation, and thus more strongly implicated than egg yolks, butter or sirloin tips in triggering high cholesterol levels in the body.

All of which means it’s probably time for health-concerned people everywhere to reconsider what we thought we knew about cholesterol, and its real role in making or breaking our health.

Cholesterol Basics

The first thing to know: Cholesterol and fat are not the same. Cholesterol is a white, waxy substance found in fat. It’s one of a group of compounds called lipids, which are vital to the body’s basic functions.

The body uses cholesterol for a variety of critically important purposes: to make and repair cell membranes, and to communicate between cells, absorb vitamin D, and produce hormones — including estrogen and testosterone. Lipoproteins are also part of our immune system, where they bind and neutralize bacteria, viruses and toxins.

“Cholesterol is an essential component of our physiology,” explains Mark Hyman, MD, medical director of the UltraWellness Center in Lennox, Mass., and author of The UltraMind Solution: Fix Your Broken Brain by Healing Your Body First.

Cholesterol is also an important repair substance: It concentrates wherever the body has an infection, wound or other source of inflammation (which is how it gets involved in arterial plaques, but we’ll get to that in

a moment).

The average person ingests between 200 and 300 milligrams (mg) of cholesterol a day from animal-derived foods, such as cheese, egg yolks and meat. But that’s only a small portion of the body’s normal cholesterol requirement. The liver makes up the difference (roughly 1,000 mg daily in a normal, healthy person), generating cholesterol from a variety of fats, proteins and carbohydrates available in the bloodstream.

“When we eat large amounts of cholesterol, our body’s production goes down,” writes Ravnskov in Fat and Cholesterol are GOOD for You!: What REALLY Causes Heart Disease. “When we eat small amounts, it goes up.”

But as noted, your body also regulates its cholesterol production — and, thus, the concentration of cholesterol in your blood — based on its needs for the substance. And one of the things that dictates the body’s level of need is the presence of free radicals, infection and inflammation.

The more inflammation, oxidation or irritation present in the body, the more cholesterol the body produces in an effort to help tackle the problem.

“Cholesterol is much more of a good guy than a bad guy,” writes Rogers in The Cholesterol Hoax. “Cholesterol is a messenger giving you a last-ditch warning.” One shouldn’t kill the messenger, says Rogers, “just because he brought you the message that you are in trouble.”

The cholesterol-as-hero story is not entirely difficult to swallow: After all, we’ve heard about those high-density lipoproteins (HDL) known as “good” cholesterol. But haven’t we also been led to believe that some components of cholesterol — those dastardly low-density lipoproteins (LDL) — are the ones swelling and clogging our arteries?

According to the alternative-view crowd, it’s not that simple. Not only is high LDL cholesterol not the cause of this arterial inflammation, says Ravnskov, it is actually “a noble knight” that, working with other lipoproteins, “is an important actor in our immune system,” valiantly striving to repair damage already done.

Here’s how it works: Uncontrolled blood sugar, free-radical activity, toxins and other pro-inflammatory factors inflame and corrode arteries by creating microscopic tears in the arterial walls. The body attempts to patch and heal the tears by putting down a thin layer of cholesterol, which acts like spackle or plaster.

But if the root causes of arterial damage (i.e., the presence of unchecked inflammation) go unaddressed, those well-intended cholesterol-composed plaques begin to accumulate and stiffen. Eventually, if irritated and inflamed, they can burst, blocking the arteries with debris and setting the stage for a heart attack.

Whether or not this buildup is likely to occur depends in part on the nature of your cholesterol and how it is being transported through your body.

Cargo Confusion

Neither fat nor cholesterol dissolves in blood, so the body ingeniously packs fat molecules inside protein-laced particles called lipoproteins. These are either low-density lipoproteins (LDL) or high-density lipoproteins (HDL).

“Think of the basic cholesterol molecule as a single, brick-size package,” says Byron Richards, a clinical nutritionist in Minneapolis. “Think of LDL and HDL as UPS trucks that cart loads of those packages around.” Both LDL and HDL transport cholesterol in the body. But they do it in different ways and are packed at different densities. LDL particles are (as their name implies) less densely packed vehicles. HDL particles, conversely, are smaller and packed more tightly.

To simplify LDL and HDL for the public, scientists have labeled HDL as “good” for the heart (in part because it helps transport cholesterol away from the arteries and back to the gut for elimination) and LDL as “bad.” But those labels gloss over some very important facts.

For one thing, LDL is critical for transporting cholesterol to cells in need of it. But researchers believe that under certain biochemical conditions, some LDL particles become smaller and denser than they are designed to be. They begin acting like little pieces of sand, lodging in arterial walls. One of the things that renders these lipid particles smaller and denser, says Hyman, is “insulin resistance as a result of eating too much sugar and refined carbohydrates, which drives a whole set of metabolic downstream effects.”

And when these small and dense LDL particles become oxidized as a result of free-radical activity, the situation gets worse: Some LDL turns into sticky foam cells that start the buildup of cholesterol deposits in your arteries. That oxidation can be triggered by anything that triggers inflammation, says Hyman, “whether it’s an inflammatory diet — like processed and junk foods and trans fats and too much sugar — infection, allergens, toxins, nutritional deficiencies or stress.” In other words, it is not cholesterol itself that is dangerous. It is how the body modifies it, under certain inflammatory conditions, that makes it threatening.

Pick Your Battles

Ask virtually any conventional doctor and he or she will tell you that lowering cholesterol is an effective way to lower heart disease. But ask those like Rogers, Ravnskov and Enig, all of whom have spent decades decoding the studies, and you’ll get a drastically different opinion. They point to studies that show little or no meaningful risk reduction from artificially lowering cholesterol levels,

and they posit that lowering inflammation through good nutrition, exercise and stress management delivers far more promising long-term health outcomes.

“The real message here is that, in the absence of inflammation, cholesterol is not the problem we once thought it was,” says Hyman. In other words, cholesterol is not the real enemy — inflammation is. And inflammation is primarily driven not by dietary cholesterol or saturated fats, but rather by trans fats, sugar, refined carbs and a sedentary lifestyle, or by the presence of an infection or other irritation in the body.

Nevertheless, in part because attempts to control cholesterol by conventional low-fat dietary recommendations have not been effective, pharmaceutical companies are raking in record profits selling cholesterol-lowering drugs, called statins, to an ever-expanding market, which now includes young children and individuals with only slightly elevated cholesterol levels.

“Although 15 million people currently take cholesterol-lowering drugs in the United States, many policymakers want to extend that to 36 million more adults, including those who don’t even have high cholesterol,” writes Rogers. “They want folks to use them prophylactically, and currently children are the next target market.”

But forcing cholesterol levels down with drugs may not deliver the benefits we’ve been led to believe, and it may also pose some real dangers. Although the potential risks of artificially depressed cholesterol levels are still being debated, critics point to research showing it can lead to memory loss, erectile dysfunction, depression, severe nutritional deficiencies, even cancer. A recent study published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal links low levels of LDL cholesterol to higher rates of cancer and premature death.

Others wonder whether dramatically lowering cholesterol — particularly without addressing underlying causes of inflammation — may give people a false sense of security and make them less likely to make the lifestyle changes required to protect their health in a meaningful way.

For these reasons, even if your cholesterol levels are sky high, statins may not be the best or most effective long-term solution for bringing them down.

Are Statins Good?

The longstanding misunderstandings about cholesterol’s role in heart disease have led both medical professionals and drug makers down treatment paths with questionable outcomes. Impressed by statins’ effectiveness in lowering cholesterol levels, many doctors have rushed to prescribe them — even though there are hundreds of studies that raise important questions about whether statins reliably and effectively improve health or heart-disease outcomes.

Statins, which work by interfering with a gene that produces an enzyme the liver uses to make cholesterol, now rank among the best-selling drugs in the United States, generating sales of nearly $20 billion in 2007. Last summer, the American Academy of Pediatrics came out in support of prescribing statins for children with high cholesterol levels resulting from garden-variety obesity (as opposed to dyslipedemias and other rare genetic abnormalities that make it impossible for the body to balance cholesterol).

These recommendations have drawn widespread criticism, particularly among health professionals alarmed that merely lowering the marker of inflammation without addressing underlying causes presents an increased rather than decreased health threat to the individuals being treated.

Knopp expresses the concern that a drug-first approach is also likely to delay or deter more promising interventions. “Treating obese children with cholesterol drugs doesn’t make any sense; the focus needs to be squarely on diet and exercise.”

Other critics point to the lack of long-term safety data (recent evidence suggests a host of potential statin side effects, such as muscle damage, dementia and impotence) and the possibility that artificially lowering children’s cholesterol could impede normal growth and development. (Remember, cholesterol is necessary for healthy cellular reproduction and hormone function.)

Although many physicians draw the line at treating children with statins, the pressure to prescribe the drugs to even relatively healthy adults is growing increasingly difficult to resist. And the average person’s likelihood of receiving a “high cholesterol” diagnosis has increased dramatically — even if his or her cholesterol levels have remained unchanged. That’s because the rise of statins has correlated directly with the lowering of what doctors now consider an “optimal” level of LDL cholesterol.

Less than 10 years ago, an LDL cholesterol level of under 130 mg was considered fine. But the guidelines, updated in 2004, lowered the “optimal” level of LDL to less than 100 mg and nudged doctors with patients at very high risk of heart disease to aim for less than 70. (A more recent study suggests 55 mg is an even better target.)

The only way to push levels that low is with drug therapy. And if every doctor followed the guidelines to the letter, 36 million Americans would be on statins.

That’s a windfall for the drug makers, but is it a boon for patients? Not according to a review published last year in the British health journal Lancet. When researchers looked at the drugs’ ability to prevent heart attacks, they found no evidence showing statins can protect women (for whom HDL is the key lipoprotein), nor did they find a benefit in men and women over age 69 — presumably the same group many doctors are trying to help.

A lot of people — doctors and patients alike — want a quick fix, so they take drugs to make the cholesterol score look better, says Richards. “The problem is that a better cholesterol score doesn’t necessarily equate to better health.”

Hyman agrees: “If you’re doing things that are driving small particle size and things that drive oxidation, like eating a high-sugar diet, for example, you can take all the Lipitor medication you want — it doesn’t work. We need to deal with the underlying cause.”

Rogers puts it even more bluntly: “To take a cholesterol-lowering drug is like seeing the red oil light in your car go on and smashing it with a hammer.”

In reality, having low cholesterol doesn’t mean you have a healthy body — or a healthy heart. A study published in the January issue of the American Heart Journal found that nearly 75 percent of patients hospitalized for a heart attack had cholesterol levels that fell within the recommended guidelines. Plus, more than 20 percent of those studied were already taking statins.

“The take-home message is not to be afraid of your cholesterol,” says Suzy Cohen, RPh, author of The 24-Hour Pharmacist. Instead, take a step back from both diet fads and quick-fix drugs and look at the big picture. Make the lifestyle adjustments that are known to address the major underlying causes of heart disease, i.e., poor nutrition, lack of exercise and inflammation.

To rely on statins without determining whether inflammation, infection or another health issue is at the root of the problem can put you in peril, says Cohen. “Lowering cholesterol in your body is the equivalent of blowing smoke out of your house while a smoldering fire remains.”

How to Conquer High Cholesterol

Lower your inflammation, and watch your cholesterol fall in line.

Here are six ways to right-size your cholesterol, reduce your heart-disease risk factors and get a whole lot healthier in the process:

- Eat less sugar and flour. Refined flours and sugars not only spark inflammation, they elevate triglycerides, a potentially dangerous form of cholesterol. Too many triglycerides in the blood impede the circulation of healthy cholesterol, causing the entire system to break down, explains Byron Richards, a clinical nutritionist in Minneapolis. When choosing grain products, look for those made with whole and sprouted grains. Avoid sugary cereals, cookies, cakes and other sweets, and minimize your intake of pastas and breads made with refined flours.

- Eat more vegetables, fruits and whole foods. The antioxidants and phytonutrients in vegetables, fruits, legumes and whole grains help protect cholesterol in the blood from free-radical damage, says Richards. They are also high in fiber (see below), which assists the body in ridding itself of cholesterol-laden bile. Worth noting: The Harvard Nurses’ Health Study and Health Professionals Follow-Up Study both showed that participants who ate five or more servings of vegetables and fruits a day had a 25 percent lower risk of heart attack and stroke than those who ate the fewest servings.

- Prioritize quality fats over junk fats. That means nixing trans fats entirely, and avoiding high-fat processed and fried foods in favor of healthy, nutrient-dense whole foods. Enjoy nuts, seeds, fish, avocados and olive oil — and don’t feel you need to cut out saturated fats entirely, either. The body craves these and requires them for proper cell, nerve and brain function, says Richards. Plus, when people don’t satisfy their flavor and satisfaction desires for saturated fats, they’ll often substitute processed carbohydrates instead, thereby increasing weight gain and inflammation. When selecting meat and dairy, choose minimally processed foods, ideally from pastured, free-range and grass-fed animals. These have more nutrients the body needs and fewer pro-inflammatory fats, says Sally Fallon, president of the Weston A. Price Foundation and coauthor of Eat Fat, Lose Fat. And whole eggs are fine: Research published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutritionshows that people eating up to seven eggs a week are no more likely to experience heart attacks or strokes than those who eat less than an egg a week.

- Befriend fiber. Eating more soluble fiber is one of the easiest ways to lower your cholesterol naturally, says Suzy Cohen, RPh, author of The 24-Hour Pharmacist. That’s because fiber binds to bile, which is composed of cholesterol and triglycerides, and escorts it (along with a variety of pro-inflammatory toxins) out of the body. The body then produces fresh bile, making use of cholesterol and triglycerides that would otherwise accumulate in the bloodstream. “Just eating two high-fiber foods a day can make a big difference,” she says. Nuts, whole grains, vegetables and berries are all high in fiber, but legumes (like kidney, lima, pinto beans and black-eyed peas) are perhaps the very best source. “Legumes have hormone-regulating properties that help regulate insulin and make sure cholesterol behaves itself,” says Richards. Licensed nutritionist Karen Hurd of Fall Creek, Wis., regularly recommends three daily half-cup servings of legumes to her clients battling inflammation-based health problems. Not a big fan of beans? “You can substitute 2 teaspoons of psyllium husk mixed in a glass of water” for one or more of those servings, says Hurd.

- Get a Move On. Moderate to intense exercise lowers cholesterol overall and raises the relative levels of protective HDL. Exercise also helps reduce excess weight and moderate the negative, inflammatory effects of stress. A 2006 Duke study that examined the effects of exercise on inactive, overweight adults found that, after six months, many of the factors putting them at risk for heart disease had reversed or improved.

This Post Has 0 Comments